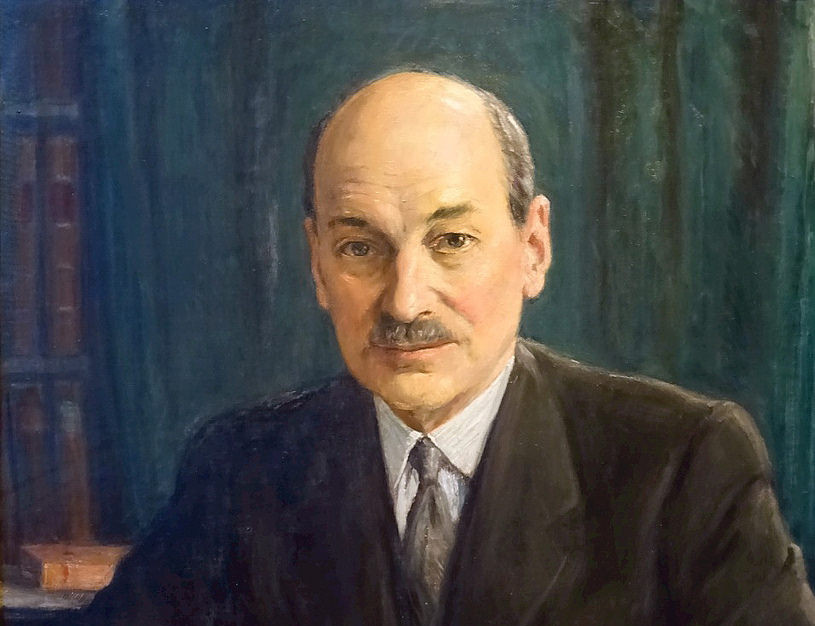

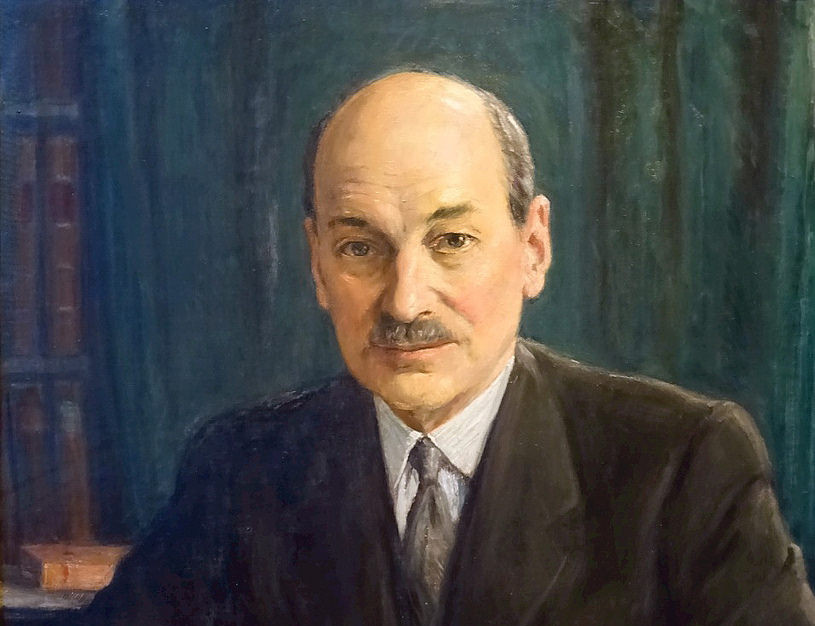

In 1951 Clement Attlee received this message from 15-year-old Ann Glossop, who had completed her final exams at Penrhos College only to discover that under recent reforms she was considered too young to graduate and must wait a year and go through them again:

Would you please explain, dear Clement

Just why it has to be

That Certificates of Education

Are barred to such as me?

I’ve worked through thirteen papers

But my swot is all in vain

Because at this time next year

I must do them all again.

Please have pity, Clement,

And tell the others too.

Remove the silly age-limit

It wasn’t there for you.

He replied:

I received with real pleasure

Your verses, my dear Ann.

Although I’ve not much leisure

I’ll reply as best I can.

I’ve not the least idea why

They have this curious rule

Condemning you to sit and sigh

Another year at school.

You’ll understand that my excuse

For lack of detailed knowledge

Is that school certs were not in use

When I attended college.

George Tomlinson is ill, but I

Have asked him to explain

And when I get the reason why

I’ll write to you again.

He lost office shortly thereafter, so Ann’s problem was never solved.