The Book of Common Prayer includes a Table of Kindred and Affinity that lists prohibited degrees of marriage in the Church of England. For example, a man may not marry his daughter’s son’s wife, and a woman may not marry her husband’s mother’s father. In this case, the two proscriptions correspond — they describe the same relationship “from both sides,” so this union is prohibited to both parties in the relationship. But is this always the case? Is each union that’s denied to a man also denied to the woman? (The table lists only heterosexual unions.) It’s not immediately clear; 25 prohibited degrees are listed for each sex, and our language makes it hard to “reverse” the description of a relationship mentally.

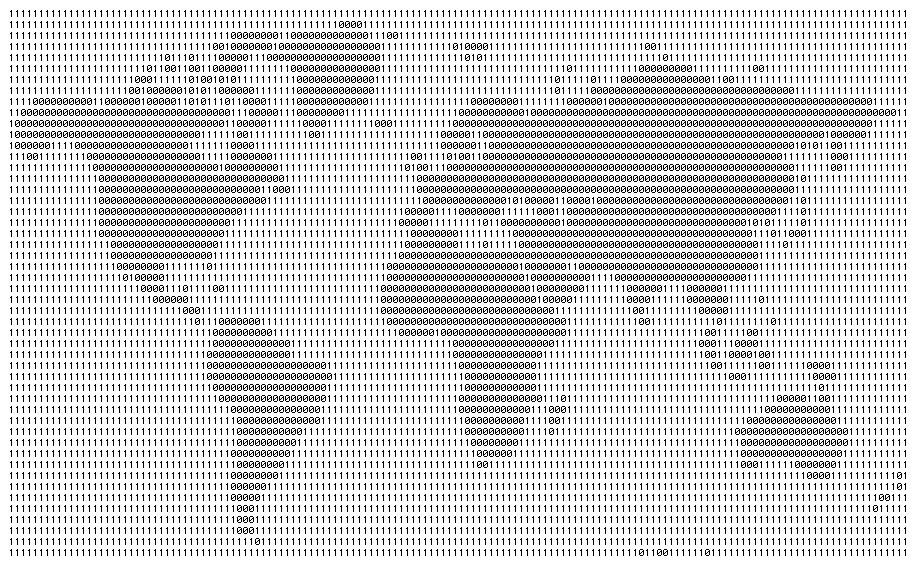

In 1989 Manchester Polytechnic mathematician M.D. Stern worked out a notation that makes this easy. Use 1 to denote a male and 0 a female, and use this code to denote relationships between individuals:

00 spouse

01 parent

10 child

11 sibling

Now, to show the relationship between one person and another, write one digit for the first person followed by a sequence of three more digits — two to represent the relationship and one to represent the sex of the second person. So, taking the example above, a man’s daughter’s son’s wife would be denoted:

1 100 101 000

To interpret the same relationship from the woman’s point of view, we just reverse the order of the digits:

0 001 010 011

He is her husband’s mother’s father.

Applying this to the prohibited degrees in the table, Stern found that every prohibition for a man corresponds to an inverse prohibition for a woman — there are no prospective marriages that would be prohibited to one party but not the other.

(M.D. Stern, “A Notational Device for Analysing Relationships,” Mathematical Gazette 73:463 [March 1989], 37-40.)