“The not distinguishing where things should be distinguished, and the not confounding where things should be confounded, is the cause of all the mistakes in the world.” — John Selden

A Planned And

Martin Gardner offered this curiosity in the August 1998 issue of Word Ways: Roll two six-sided dice. If they show a total of 6 or 8, roll them again. Otherwise, go to the chapter of Genesis (the King James version) that corresponds to the total on the dice. Now turn both dice upside down and go to the verse whose number is now displayed. The first word of that verse will always be And.

(Martin Gardner, “Mysterious Precognitions,” Word Ways 31:3 [August 1998], 175-177.)

Pangrammatic Loops

A marvelous variation on self-inventorying lists, from the inimitable Lee Sallows:

Recalling that a self-enumerating pangram corresponds to a closed loop of length 1, here follows a loop of length 2, which is to say, a pair of pangrams that enumerate each other. The pangrams are both minimal in the sense of containing none but essential letters with no “and”s or other devices openly or surreptitously added.

ONE A, ONE B, ONE C, ONE D, THIRTYONE E, FOUR F, ONE G, FIVE H, FIVE I, ONE J, ONE K, ONE L, ONE M, TWENTYTWO N, SEVENTEEN O, ONE P, ONE Q, SEVEN R, FOUR S, ELEVEN T, THREE U, FIVE V, FOUR W, ONE X, THREE Y, ONE Z.

ONE A, ONE B, ONE C, ONE D, THIRTYTWO E, SEVEN F, ONE G, FOUR H, FIVE I, ONE J, ONE K, TWO L, ONE M, TWENTY N, NINETEEN O, ONE P, ONE Q, SEVEN R, THREE S, NINE T, FOUR U, SEVEN V, THREE W, ONE X, THREE Y, ONE Z.

An alternative (non-minimal) pair includes plural s’s:

ONE A, ONE B, ONE C, ONE D, TWENTYSEVEN E’S, SIX F’S, ONE G, THREE H’S, SIX I’S, ONE L, TWENTY N’S, SIXTEEN O’S, ONE P, ONE Q, SIX R’S, NINETEEN S’S, TWELVE T’S, FOUR U’S, FOUR V’S, FIVE W’S, THREE X’S, FOUR Y’S, ONE Z.

ONE A, ONE B, ONE C, ONE D, TWENTYNINE E’S, FIVE F’S, ONE G, THREE H’S, SEVEN I’S, ONE J, ONE K, TWO L’S, ONE M, TWENTY N’S, SIXTEEN O’S, ONE P, ONE Q, SIX R’S, TWENTY S’S, TEN T’S, FOUR U’S, THREE V’S, FOUR W’S, FIVE X’S, THREE Y’S, ONE Z.

In similar vein, pangrammatic loops of length 3 follow, but now in shorthand, using arabic numerals to stand for number words, i.e. 1 = one, 2 = two, etc. The first list is enumerated by the second, the second by the third and the third by the first. The 1st loop contains minimal pangrams, the 2nd, pangrams with plural s’s:

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z 1 1 1 1 31 5 1 5 9 1 1 1 1 20 16 1 1 5 5 11 1 4 3 4 2 1 1 1 1 1 28 7 1 3 8 1 1 2 1 20 18 1 1 5 2 8 3 6 3 2 3 1 1 1 1 1 31 2 5 9 7 1 1 1 1 16 15 1 1 5 3 16 1 3 6 2 3 1 A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z 1 1 1 1 32 5 2 3 7 1 1 1 1 22 18 1 1 3 19 14 2 6 7 2 3 1 1 1 1 1 32 3 2 6 6 1 1 1 1 20 18 1 1 6 19 16 2 4 7 2 3 1 1 1 1 1 27 2 2 5 8 1 1 1 1 19 17 1 1 5 21 14 2 2 6 5 3 1

Here also a minimal pangrammatic loop of length 4 (no equivalent using plural s’s exists):

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z 1 1 1 1 25 4 2 4 7 1 1 2 1 16 18 1 1 5 5 11 3 4 5 4 2 1 1 1 1 1 28 9 2 3 7 1 1 2 1 16 18 1 1 6 3 9 5 7 5 2 2 1 1 1 1 1 30 3 3 5 9 1 1 1 1 20 15 1 1 3 5 12 1 5 6 3 2 1 1 1 1 1 30 6 1 6 8 1 1 2 1 17 14 1 1 6 2 12 1 5 4 2 3 1

“There exist no minimal pangrammatic loops of length 5 or longer until we reach lengths 10, 33, and 55 (no plural s’s) and lengths 15, 22, 23, 207 and 312 (with plural s’s),” he adds. “This completes what I believe to be an exhaustive survey of all self-enumerating minimal pangrammatic loops.”

(Thanks, Lee.)

The Davenport Tablets

When the Rev. Jacob Gass discovered three inscribed slate tablets near Davenport, Iowa, in 1877, he thought they demonstrated the presence of an ancient Old World people who’d traveled to the Americas long before Columbus. The find was praised in local journals, but in 1885 ethnologist Cyrus Thomas declared them a fraud: The inscriptions were a hodgepodge of various languages amateurishly rendered, and Gass had reported finding the slates in loose soil in which human bones had been scattered about, suggested that they’d been planted there.

It turned out that the slates matched those on the roof of a nearby house of prostitution, right down to the nail holes. In 1991 archaeologist Marshall McKusick tracked down a confession by local academy member James Willis Bollinger, who said, “We had no respect for Reverend Gass because he was the biggest windjammer and liar and everyone knew he was. We wanted to shut him up once and for all.” McKusick points out that Bollinger was only 9 years old when the slates had been discovered, but perhaps he’d heard the story from other members and injected himself into the story. The modern consensus is that Gass was the victim of a hoax.

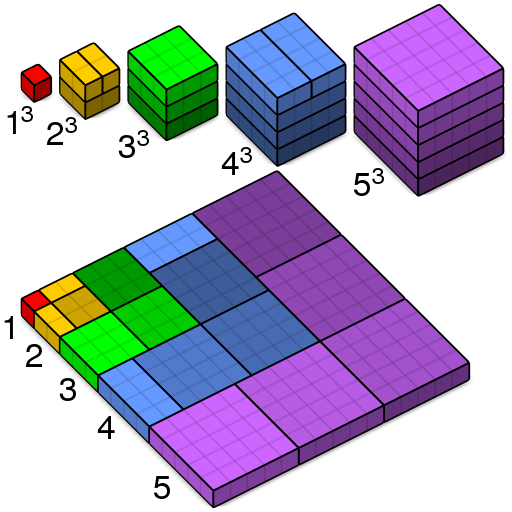

Cubes and Squares

MATLAB’s Loren Shure devised this lovely “proof without words” of Nicomachus’ theorem, that the sum of the first n cubes is the square of the nth triangular number:

R.J. Stroeker of Erasmus University wrote, “Every beginning student of number theory surely must have marveled at [this] miraculous fact.”

That Time Again

King William’s College has released its annual General Knowledge Paper, “The World’s Most Difficult Quiz,” a school tradition since 1904. There are 18 sets of 10 questions, each set treating a particular theme; divining the themes is difficult and useful.

This year’s quiz bears the customary warning at the top: Scire ubi aliquid invenire possis ea demum maxima pars eruditionis est, “The greatest part of knowledge is knowing where to find something.” If past quizzes are any model, then search engines may lead you astray.

The answers will be on the school website at the end of January. Meanwhile MetaFilter is coordinating a spreadsheet of proposed answers (warning: spoilers).

Alternatives

arithmocracy: rule by the numerical majority

millocracy: the rule of mill owners

gerontocracy: government by old men

polyarchy: rule by many people

angelocracy: government by angels

paedarchy: rule by a child or children

mesocracy: government by the middle class

dulocracy: government by slaves

isocracy: polity where all have equal power

ideocracy: government according to a particular ideology

stratocracy: government by the army

diabolarchy: rule by a devil

chrysocracy: rule of the wealthy

heroarchy: government by people who are widely admired

hetaerocracy: the rule of college fellows

chirocracy: government by a strong hand or physical force

synarchy: joint rule or sovereignty

kakistocracy: government by the worst citizens

cryptarchy: secret government

papyrocracy: government by excessive paperwork

ergatocracy: government by the workers

ptochocracy: government by the poor

nomocracy: government based on a legal code

gynarchy: government by a woman or women

pollarchy: rule by the masses

pornocracy: rule by prostitutes

hierocracy: the rule of priests

merocracy: government by a small number out of the whole

ochlocracy: government by the populace

tritheocracy: government by three gods

“The most dangerous man, to any government, is the man who is able to think things out for himself,” wrote H.L. Mencken. “Almost inevitably, he comes to the conclusion that the government he lives under is dishonest, insane, and intolerable.”

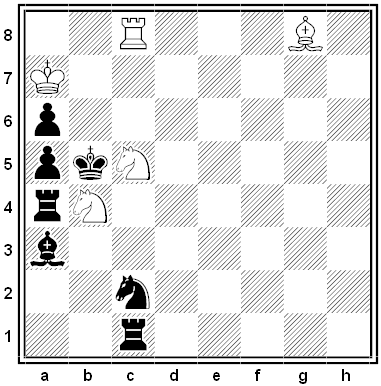

Black and White

A prizewinning problem by Paul Bekkelund from the Norwegian chess magazine Sjakk-Nytt, 1947. White to mate in two moves.

Sky Pirates

The only instance during World War I of an airship capturing a merchant vessel occurred on April 23, 1917, when the German zeppelin L 23 descended on the civilian Norwegian schooner Royal off the Danish coast. At the airship’s approach the crew abandoned the Royal in boats, and the zeppelin made a water landing to capture them.

The ship turned out to be carrying pit-props, a contraband lading, and Kapitänleutnant Ludwig Bockholt saw her conducted into the Elbe escorted by two German destroyers. “The capture of the Royal — actually a schooner of only 688 tons — hardly affected the trade war against England,” writes historian Douglas H. Robinson, “but Bockholt’s flamboyant gesture appealed particularly to the men, and tales of the exploit were told from Tondern to Hage.”

(Douglas H. Robinson, The Zeppelin in Combat, 1962.)

Truth in Advertising

Another feat of self-reference — reader Hans Havermann devised these true sentences:

“The odds of randomly picking four letters from this statement and having them be F, O, U, and R, are two out of two hundred nineteen thousand six hundred eighty-seven.”

“The odds of randomly picking four letters from this statement and having them be F, O, U, and R, are three out of two hundred ninety-two thousand nine hundred sixteen.”

These two are in lowest terms. He has seven more.

(Thanks, Hans.)