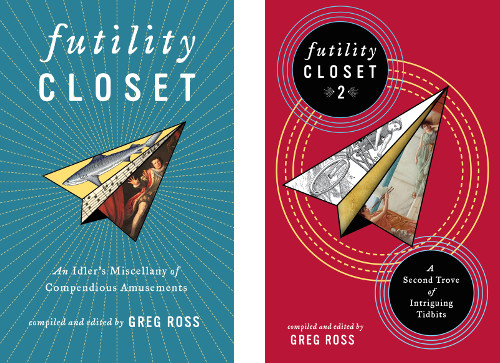

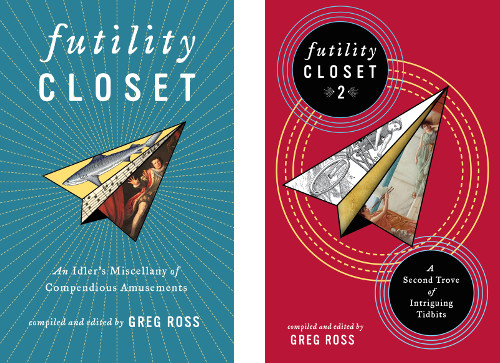

Just a reminder — Futility Closet books make great gifts for people who are impossible to buy gifts for. Both contain hundreds of hand-picked favorites from our archive of curiosities. Some reviews:

“A wild, wonderful, and educational romp through history, science, zany patents, math puzzles, wonderful words (like boanthropy, hallelujatic, and andabatarian), the Devil’s Game, self-contradicting words, and so much more. Buy this book and feed your mind!” — Clifford A. Pickover, author of The Mathematics Devotional

“Futility Closet delivers concentrated doses of weird, wonderful, brain-stimulating ideas and anecdotes, curated mainly from forgotten old books. I’m hooked — there’s nothing quite like it!” — Mark Frauenfelder, founder, Boing Boing

“Meant to be read in pieces, but impossible to put down.” — Gary Antonick, editor, New York Times Numberplay blog

“Futility Closet is a dusty museum back room where one can spend minutes or hours among seldom-seen curiosities, and feel that none of the time was wasted.” — Alan Bellows, DamnInteresting.com

Both books are available now on Amazon. Thanks for your support!