“Wealth, in even the most improbable cases, manages to convey the aspect of intelligence.” — John Kenneth Galbraith

“Wealth, in even the most improbable cases, manages to convey the aspect of intelligence.” — John Kenneth Galbraith

In 1978, two luminaries of South Korean cinema were abducted by Kim Jong-Il and forced to make films in North Korea in an outlandish plan to improve his country’s fortunes. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll tell the story of Choi Eun-Hee and Shin Sang-Ok and their dramatic efforts to escape their captors.

We’ll also examine Napoleon’s wallpaper and puzzle over an abandoned construction.

Newport, Ore., and Boston, Mass., contain signs directing motorists to one another, despite being more than 3,000 miles apart.

They’re at opposite ends of U.S. Route 20.

Likewise Sacramento, Calif., and Ocean City, Md., at either end of Route 50. Wilmington, N.C., used to reciprocate with Barstow, Calif., at the other end of Interstate 40, but gave up because the sign kept getting stolen.

It’s sometimes suggested that the modern QWERTY keyboard was designed so that typewriter salesmen could impress customers by typing the phrase TYPEWRITER QUOTE on the top row of keys.

It wasn’t, but they could.

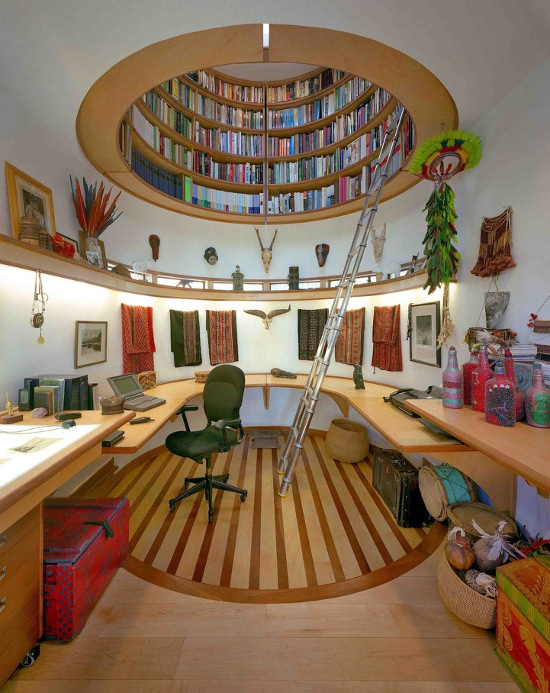

The home workspace of National Geographic Society Explorer-in-Residence Wade Davis includes an overhead library.

“The original idea I had was to put the books that meant the most to him over his head at all times, floating, above and in his head as his own, very personal lyric,” said architect Travis Price.

“The dome shape above was a tholos, the shape of a pregnant woman’s womb, similar to the rotunda of the oracle’s temple at Delphi.”

(From Alex Johnson, Improbable Libraries, 2015.)

Sign-language expressions adopted by modern monks who live in an atmosphere of silence:

bulldozer = bull + push

boiler room = boil + room

computer = I + B + M

machine = “place fists together then twirl thumbs around one another several times”

dump truck = unload + machine

tractor = red + horse

machinist = brother + work + machine

jelly department = sweet + butter + house

refrigerator = cold + house

gasoline = oil + fire

plane = metal + wing

“There are signs for turkey (thank + God + day + bird: an original sign meaning “Thanksgiving Day bird”) and hen (egg + bird) but the latter designation refers to the hen as a source of eggs and not of flesh.”

From Monastic Sign Languages, ed. Jean Umiker-Sebeok and Thomas A. Sebeok, 2011.

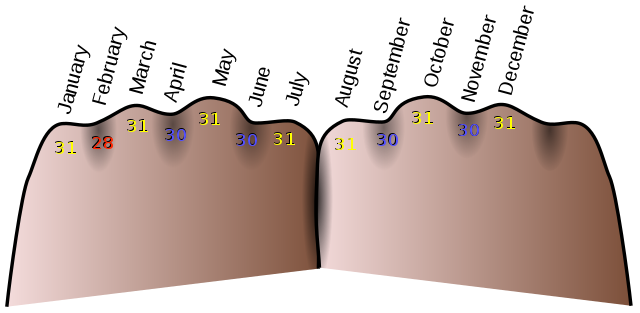

In the 1890s, traveler Henry Attwell found that the residents of rural Holland used their hands to recall which months of the year have 31 days:

The knuckles of the hand represent months of thirty-one days, and the spaces between represent months of thirty days. Thus, the first knuckle is January (thirty-one), the first space February (twenty-eight or twenty-nine, the exception), the second knuckle March (thirty-one), the second space April (thirty), &c. The fourth knuckle, July (thirty-one), is followed by the first [of the other hand], August [thirty-one], and so on, until the third knuckle is reached a second time. This sequence of two knuckles corresponds with the only sequence of months (July and August) which have each thirty-one days.

“This memoria tecnica certainly gives a more ready result than the rhyme [‘Thirty Days Hath September’].”

(From Angus Trumble, The Finger: A Handbook, 2010.)

Man: Hello, my boy. And what is your dog’s name?

Boy: I don’t know. We call him Rover.

— Stafford Beer

A writer in The Builder has cleverly suggested that bridges might be erected in the crowded thoroughfares of London for the convenience of foot passengers, who lose so much valuable time in crossing. As the stairs would occupy a considerable space, and occasion much fatigue, I beg to propose an amendment: Might not the ascending pedestrians be raised up by the descending? The bridge would then resemble the letter H, and occupy but little room. Three or four at a time, stepping into an iron framework, would be gently elevated, walk across, and perform by their weight the same friendly office for others rising on the opposite side. Surely no obstacles can arise which might not be surmounted by ingenuity. If a temporary bridge were erected in one of the parks the experiment might be tried at little cost, and, at any rate, some amusement would be afforded. C.T.

— Notes and Queries, July 17, 1852

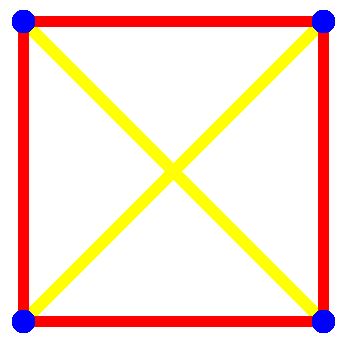

Alex Bellos set a pleasingly simple puzzle in Monday’s Guardian: How many ways are there to arrange four points in the plane so that only two distances occur between any two points? He gives one solution, which helps to illustrate the problem: In a square, any two vertices are separated by either the length of a side or the length of a diagonal — no matter which two points are chosen, the distance between them will be one of two values. Besides the square, how many other configurations have this property?

The puzzle comes originally from Dartmouth mathematician Peter Winkler, who writes, “Nearly everyone misses at least one [solution], and for each possible solution, it’s been missed by at least one person.”