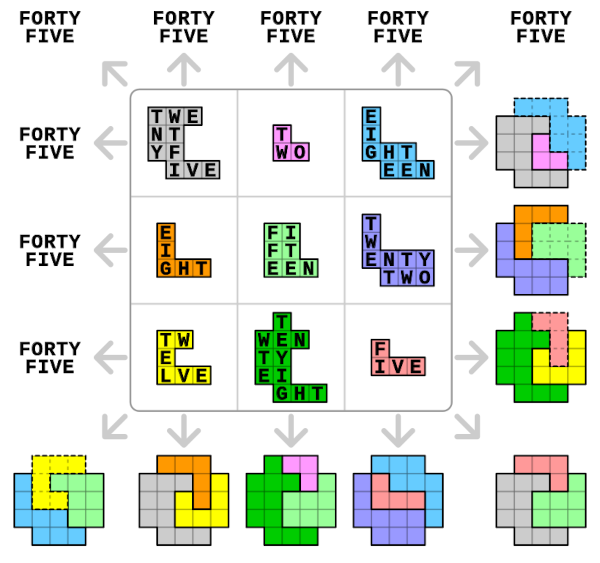

From Lee Sallows:

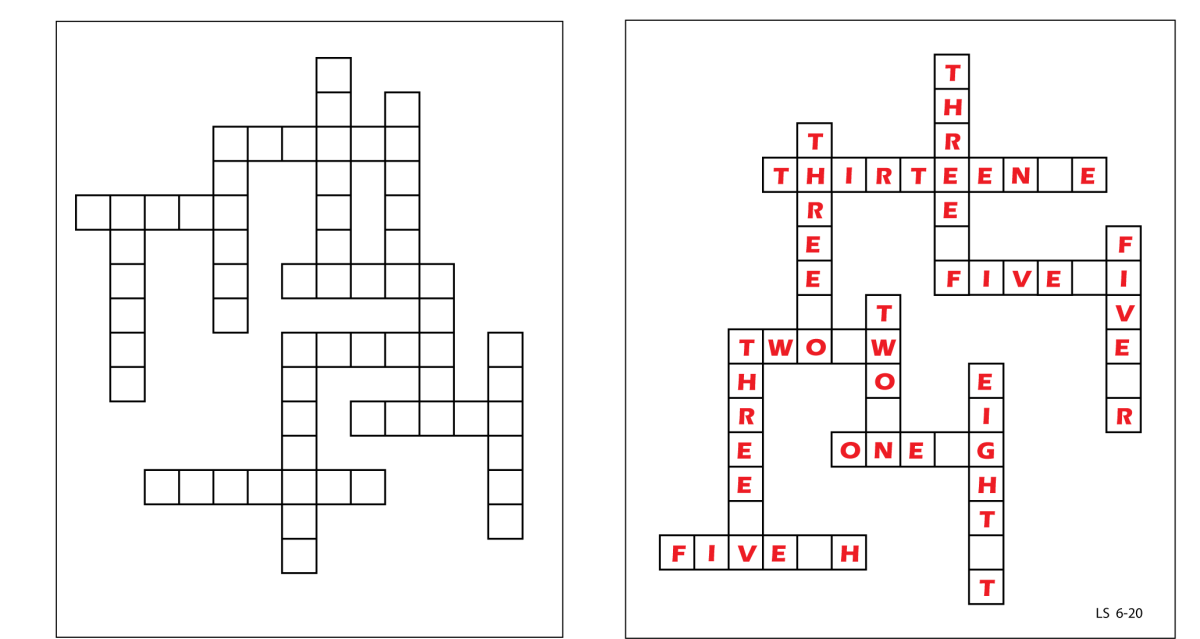

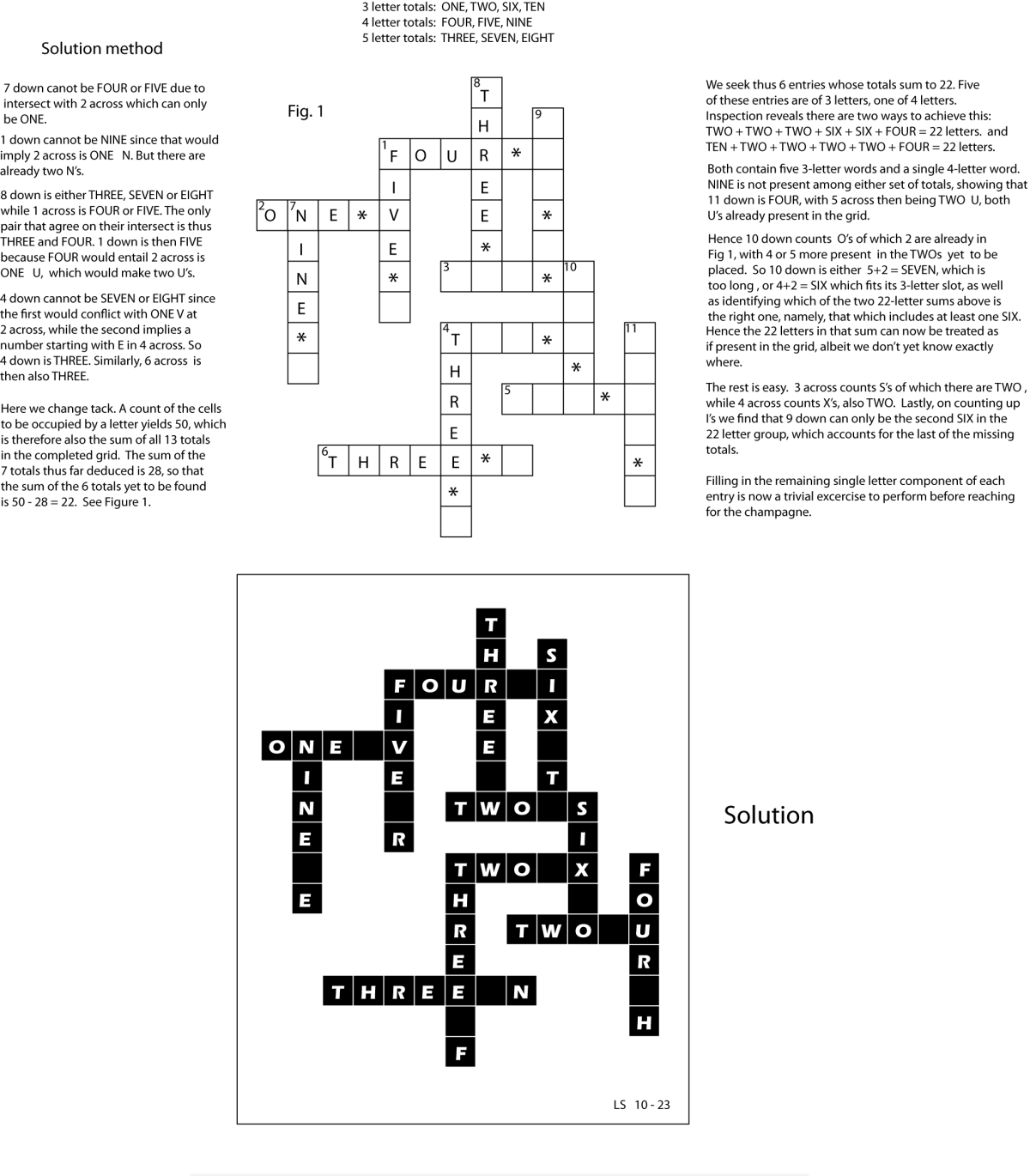

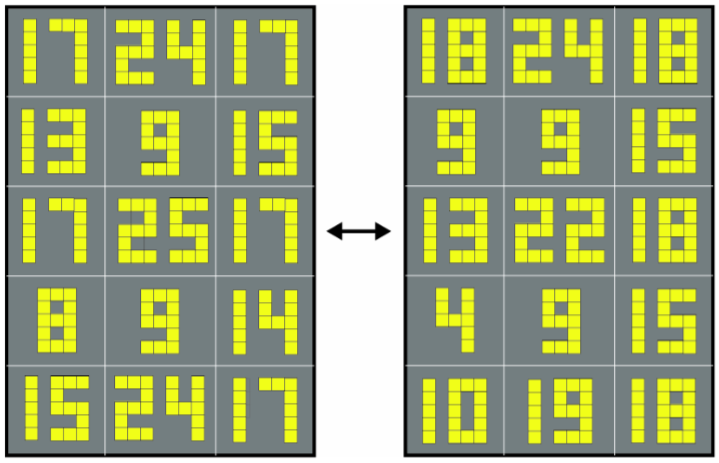

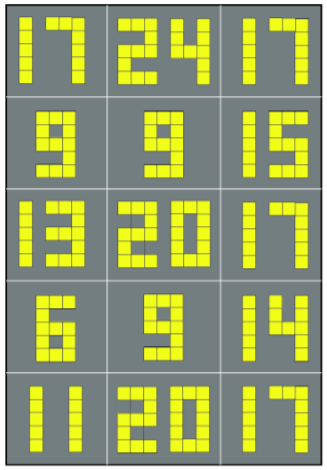

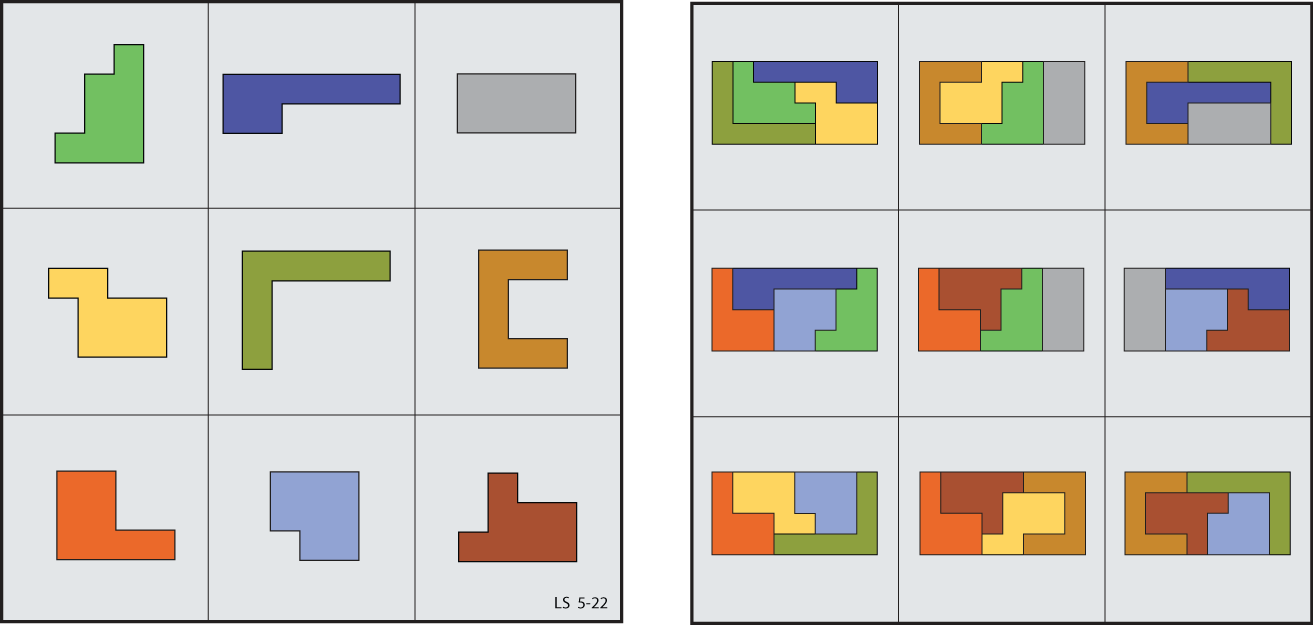

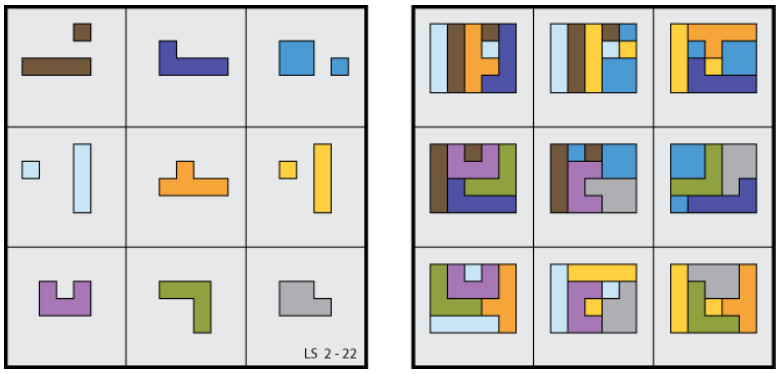

Can you complete the ‘self-descriptive crossword puzzle’ at left below? As in the solution to a similar puzzle seen at right, each of its 13 entries, 6 horizontal, 7 vertical, consists of an English number name folowed by a space followed by a distinct letter. The number preceding each letter describes the total number of occurrences of the letter in the completed puzzle. Hence, in the example, E occurs thirteen times, G only once, and so on, as readers can check. Note that the self-description is complete; every distinct letter is counted.

Though far from easy, the self-descriptive property of the crossword enables its solution to be inferred from its empty grid using reasoning based on orthography only.