In the Japanese logic puzzle Akari, you’re presented with a grid of black and white squares. The goal is to place “light bulbs” into white cells until the whole grid is illuminated. Each bulb sends out rays of light horizontally and vertically, illuminating its row and column unless a black cell blocks the rays.

There are two constraints: The bulbs must not shine on one another, and each numbered black cell must bear that many bulbs (orthogonally adjacent to it) in the finished diagram. An unnumbered black cell can bear any number of bulbs.

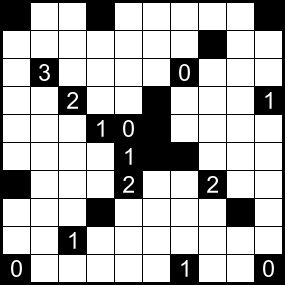

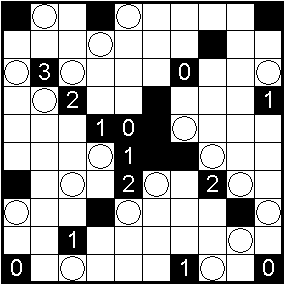

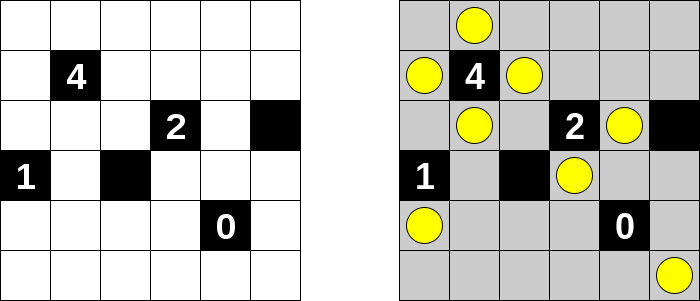

Here’s a moderately difficult puzzle. Can you solve it?