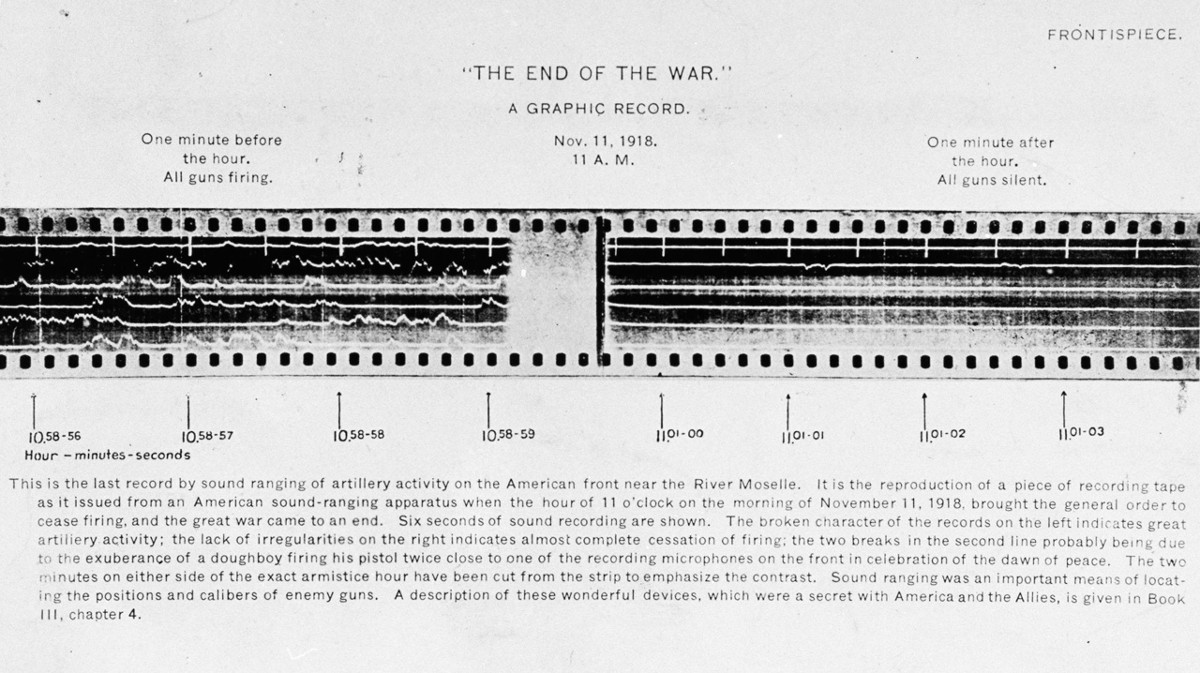

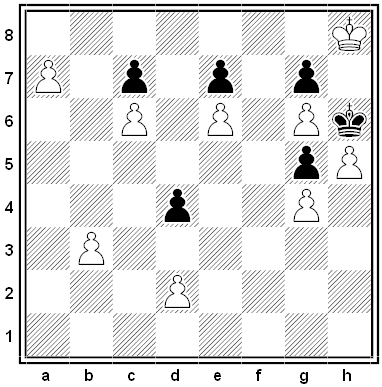

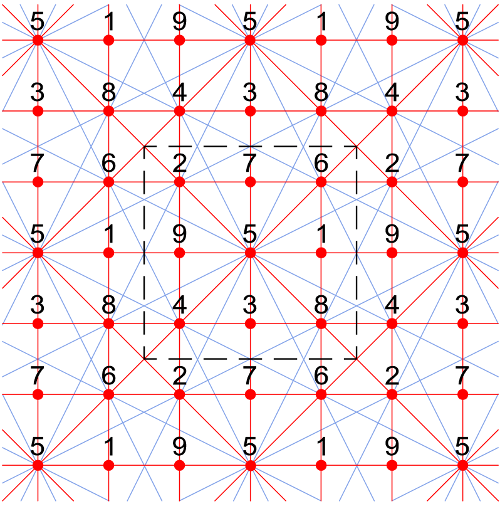

World War I’s final ceasefire went into effect at a precise moment: 11:00 a.m. Paris time on Nov. 11, 1918. The French had worked out a way of recording sound signals on film — they used it to infer the position of enemy guns by determining the time between the sound of a shell’s firing and its explosion. This gives us a visual record of the end of the fighting, six representative seconds from the periods before and after the armistice. (Note, though, that the minute immediately before and the one immediately after the ceasefire aren’t shown, “to emphasize the contrast.”)

I don’t have an original source for this — Time magazine credits the U.S. Army Signal Corps.