To read good books is like holding a conversation with the most eminent minds of past centuries and, moreover, a studied conversation in which these authors reveal to us only the best of their thoughts.

— René Descartes, Discourse on the Method, 1637

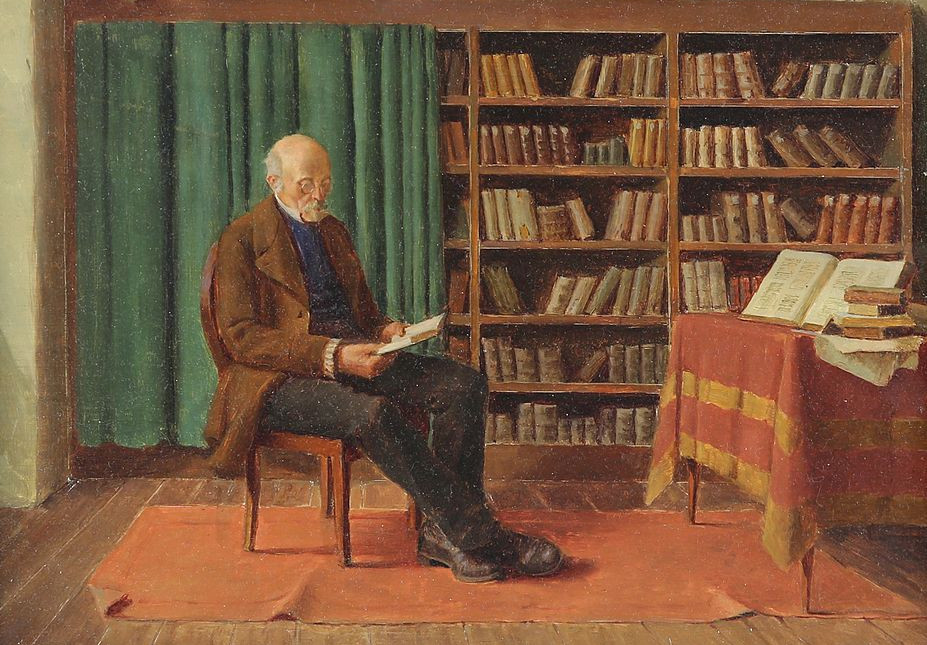

For him, books were like friends, and reading an extension of companionship — a way of expanding beyond the circumference of time and place the circle of one’s kindred acquaintances.

— Michael Holroyd, Lytton Strachey, 1971

‘There is nothing like books’; — of all things sold incomparably the cheapest, of all pleasures the least palling, they take up little room, keep quiet when they are not wanted, and, when taken up, bring us face to face with the choicest men who have ever lived, at their choicest moments.

As my walking companion in the country, I was so UnEnglish (excuse the two capitals) as on the whole, to prefer my pocket Milton which I carried for twenty years, to the not unbeloved bull terrier Trimmer, who accompanied me for five — for Milton never fidgeted, frightened horses, ran after sheep or got run over by a goods-van.

— Samuel Palmer, letter to Charles West Cape, Jan. 31, 1880

In a very real sense, then, people who have read good literature have lived more than people who cannot or will not read. … It is not true that we have only one life to live; if we can read, we can live as many more lives and as many kinds of lives as we wish.

— S.I. Hayakawa, Language in Thought and Action, 1952