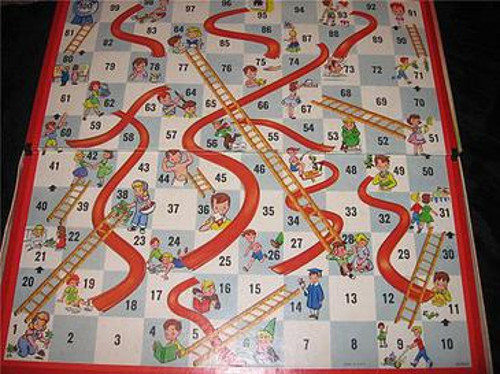

Based on an ancient Hindu game, Snakes and Ladders (Chutes and Ladders in ophidiophobic America) is at heart a morality lesson: As you progress by die roll from square 1 to square 100 and spiritual enlightenment, your way is complicated by virtues and vices. Landing on a snake (or chute) will send you back to an earlier square, and landing on a ladder will send you ahead to a later one. Each of these shortcuts is associated with a precept — “Carelessness” leads to “Injury,” “Study” leads to “Knowledge,” and so on.

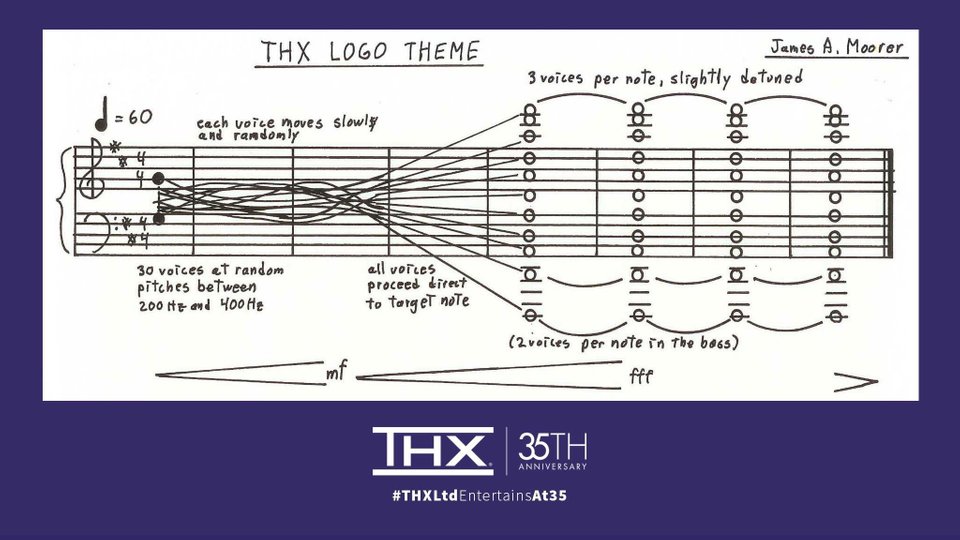

In 1993 University of Michigan mathematician S.C. Althoen and his colleagues considered the game as a 101-state absorbing Markov chain. The shortest possible game lasts seven moves, the longest is infinite, and according to their calculations the expected number of moves in the Milton Bradley version of Chutes and Ladders is

which is about 39.2.

Troublingly, the average length of a game without snakes or ladders (just the 100-square board) is almost exactly 33 moves: “Apparently the snakes lengthen the game more than the ladders shorten it.” And, while adding a ladder will generally shorten the game and adding a snake will lengthen it, this isn’t always the case: In the original game, adding a ladder from square 79 to square 81 lengthens the expected playing time by more than two moves (to about 41.9), since it increases the chance of missing the important ladder leading from square 80 to square 100. And adding a snake from square 29 to square 27 shortens the game by more than a move (to about 38.0), since it offers a second chance at the long ladder from 28 to 84.

So, arguably, we might advance more quickly through life with more vice and less virtue.

(S.C. Althoen, L. King, and K. Schilling, “How Long Is a Game of Snakes and Ladders?”, Mathematical Gazette 77:478 [March 1993], 71-76.)