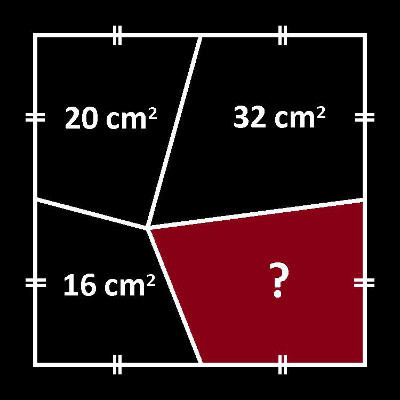

A Pretty Puzzle

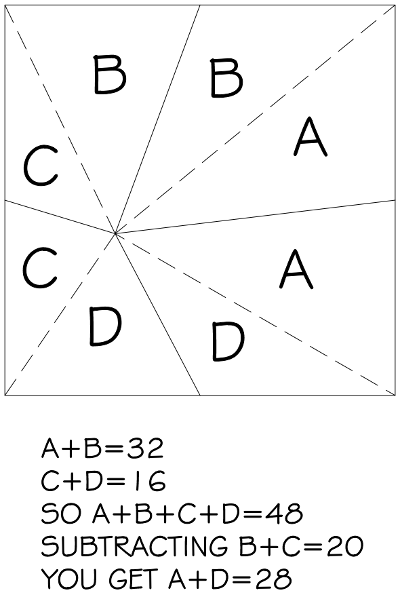

I don’t know who came up with this; I found it on r/mathpuzzles. What’s the area of the red region?

An Empty Message

“The hardest of all adventures to speak of is music, because music has no meaning to speak of. If music could be translated into human speech it would no longer need to exist. Like love, music’s a mystery which, when solved, evaporates.” — Ned Rorem, Music From Inside Out, 1967

“Music has no subject beyond the combinations of notes we hear, for music speaks not only by means of sounds, it speaks nothing but sound.” — Eduard Hanslick

“Music expresses that which cannot be said and on which it is impossible to be silent.” — Victor Hugo

But music moves us, and we know not why;

We feel the tears, but cannot trace their source.

Is it the language of some other state,

Born of its memory? For what can wake

The soul’s strong instinct of another world,

Like music?

— Letitia Elizabeth Landon, The Golden Violet, 1827

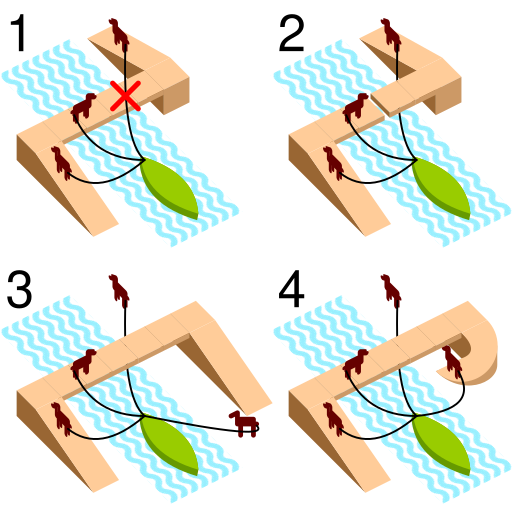

Topology

Like the Tehachapi Loop, this is a beautiful solution to a nonverbal problem. When the towpath switches to the other side of a canal, how can you move your horse across the water without having to unhitch it from the boat it’s towing?

The answer is a roving bridge (this one is on the Macclesfield Canal in Cheshire). With two ramps, one a spiral, the horse passes through 360 degrees in crossing the canal, and the tow line never has to be unfastened.

A Bite

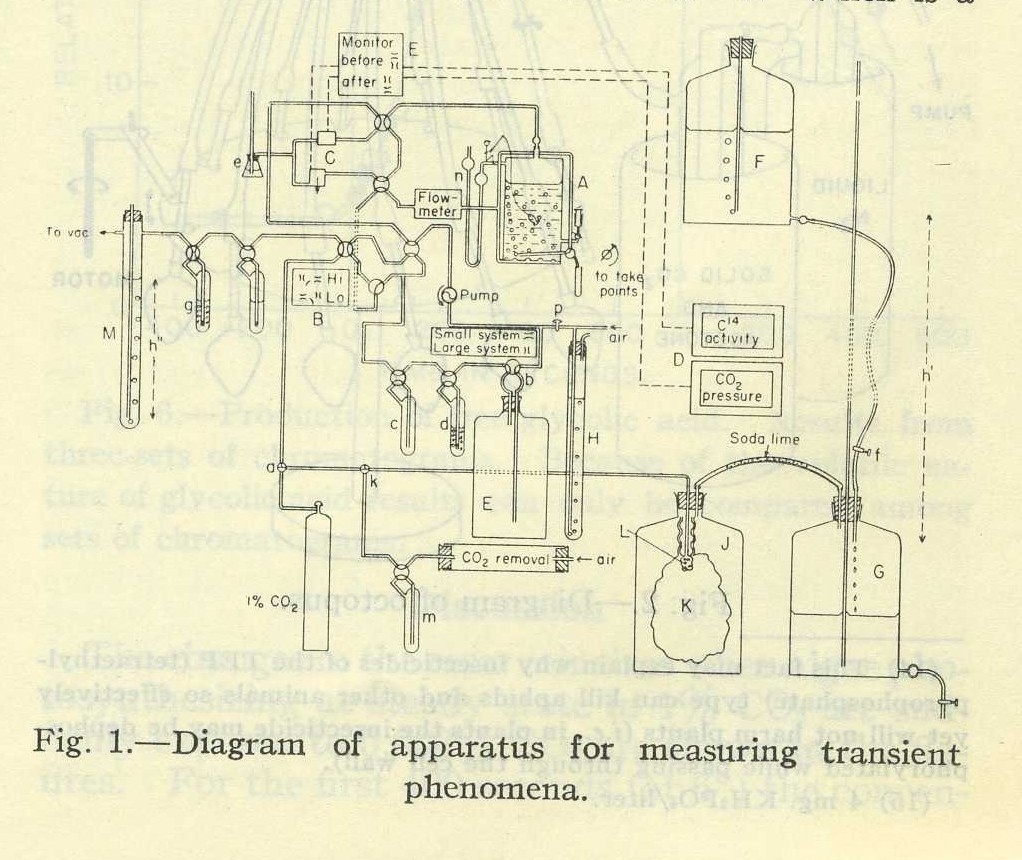

From the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Chemistry World blog: In 1955, when impish graduate student A.T. Wilson published a paper with his humorless but brilliant supervisor, Melvin Calvin, Wilson made a wager with a department secretary that he could sneak a picture of a man fishing into one of the paper’s diagrams. He won the wager — can you find the fisherman?

Love and Reasons

If I love you because you’re smart, kind, and funny, why don’t I love others who are equally smart, kind, and funny? And why does my love persist if you lose these qualities?

On the other hand, if I don’t love you because of the properties you hold, then why do I love you? I feel anger, grief, and sadness for reasons — do I feel romantic love for no reason?

It is true that I meet attractive people and fail to fall in love with them. So perhaps people don’t fall in love based on reasons. But if they do it for no reason, then it seems I might fall in or out of love with anyone, or everyone, at any time.

It seems reasonable to want to be loved for who I am, for properties I hold. But this doesn’t seem to be how it works: It’s not my properties that compel you to love me and not another. So what is it?

(Raja Halwani, Philosophy of Love, Sex, and Marriage: An Introduction, 2018.)

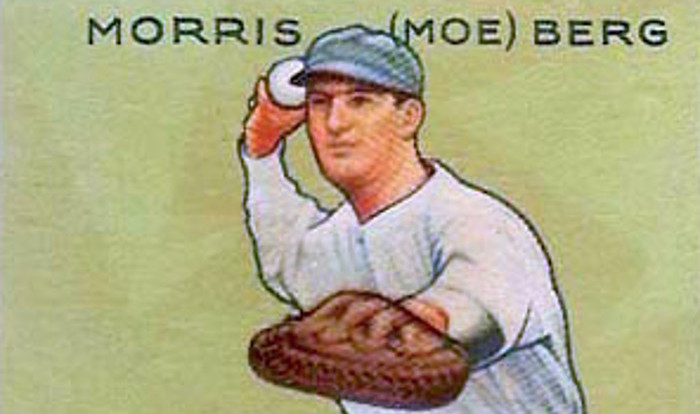

Podcast Episode 237: The Baseball Spy

Moe Berg earned his reputation as the brainiest man in baseball — he had two Ivy League degrees and studied at the Sorbonne. But when World War II broke out he found an unlikely second career, as a spy trying to prevent the Nazis from getting an atomic bomb. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll follow Berg’s enigmatic life and its strange conclusion.

We’ll also consider the value of stripes and puzzle over a fateful accident.

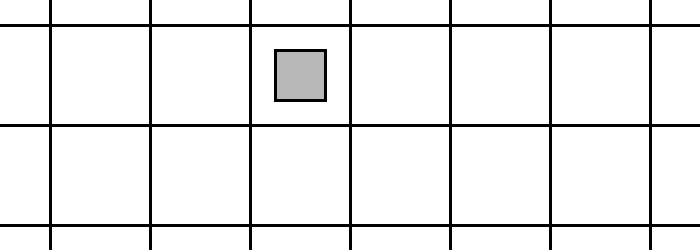

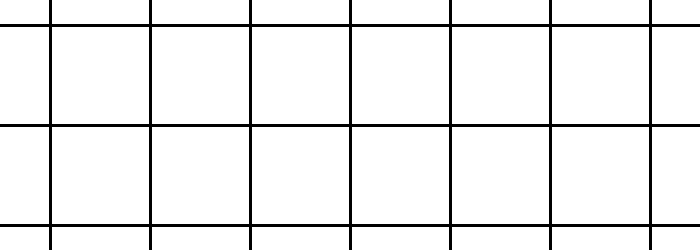

Loose Change

You’re holding a penny, and you’re standing on an infinite plane. The plane bears a grid of squares, each of which is twice the width of the penny. If you roll the penny out onto the grid, what is the probability that it will come to rest entirely within a square? (Assume the lines are of negligible thickness.)

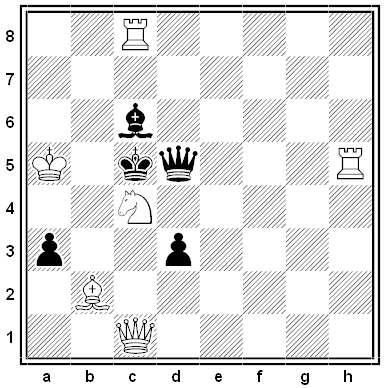

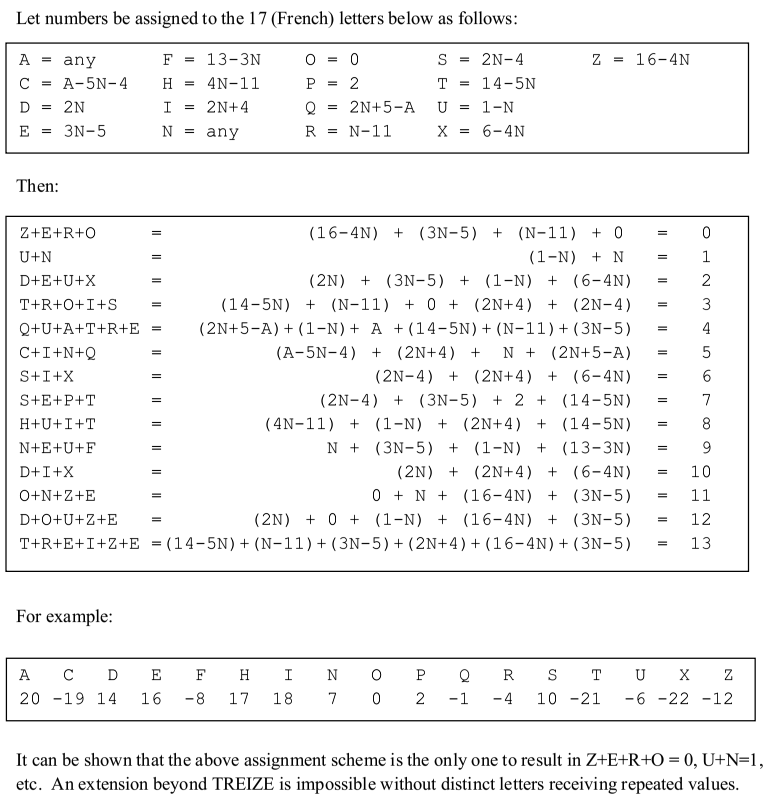

“Algebraic Theory of French Letters”

From Lee Sallows:

(Thanks, Lee!)

SAM

Sculptor Edward Ihnatowicz’s Sound Activated Mobile (SAM) was the first moving sculpture that could respond actively to its surroundings. Listening through four microphones in its head, it would twist and crane its neck to face the source of the loudest noise, like an earnest poppy.

Fascinated Londoners spent hours vying for SAM’s attention at the 1968 Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition. Encouraged, Ihnatowicz unveiled the prodigious Senster two years later.