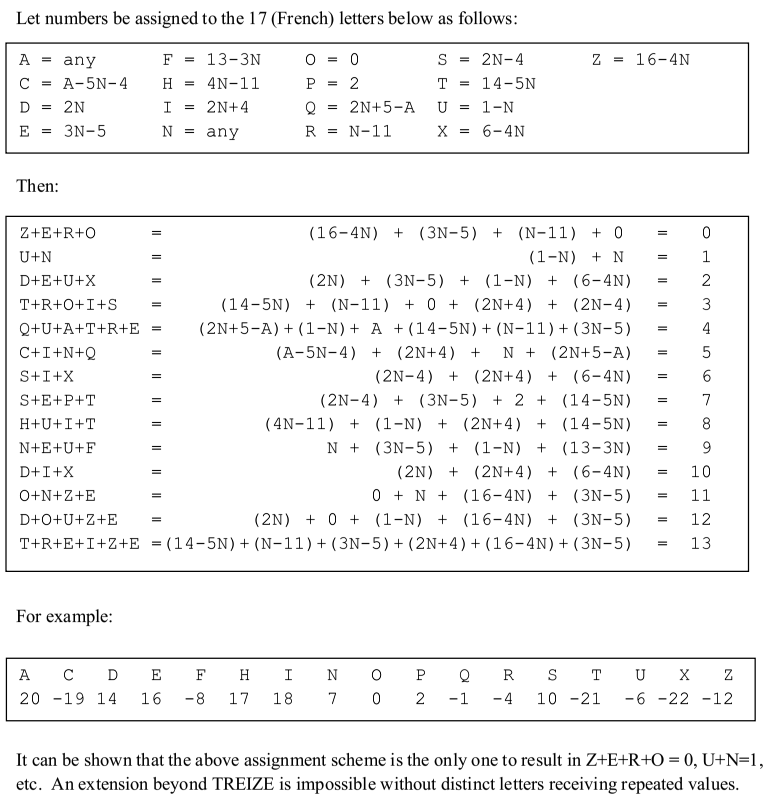

From Lee Sallows:

(Thanks, Lee!)

From Lee Sallows:

(Thanks, Lee!)

Sculptor Edward Ihnatowicz’s Sound Activated Mobile (SAM) was the first moving sculpture that could respond actively to its surroundings. Listening through four microphones in its head, it would twist and crane its neck to face the source of the loudest noise, like an earnest poppy.

Fascinated Londoners spent hours vying for SAM’s attention at the 1968 Cybernetic Serendipity exhibition. Encouraged, Ihnatowicz unveiled the prodigious Senster two years later.

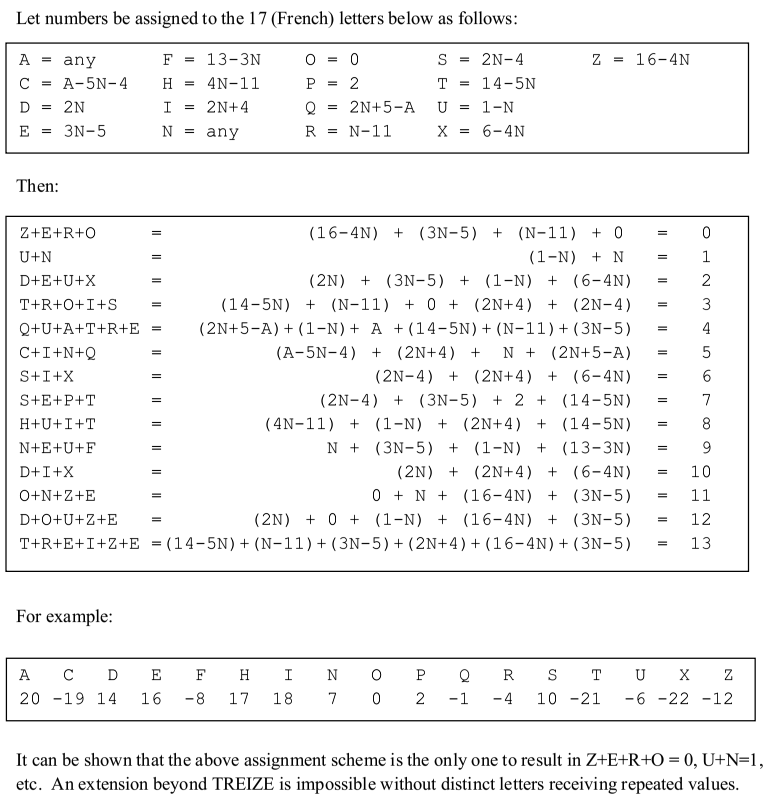

In 1958 psychologist Robert Plutchik suggested that there are eight primary emotions: joy, sadness, anger, fear, trust, disgust, surprise, and anticipation. Each of the eight exists because it serves an adaptive role that gives it survival value — for example, fear inspires the fight-or-flight response.

He arranged them on a wheel to show their relationships, with similar emotions close together and opposites 180 degrees apart. Like colors, emotions can vary in intensity (joy might vary from serenity to ecstasy), and they can mix to form secondary emotions (submission is fear combined with trust, and awe is fear combined with surprise).

When all these combinations are included, the system catalogs 56 emotions at 1 intensity level. And in his final “structural model” of emotions, the petals are folded up in a third dimension to form a cone.

Hunters of the 19th century defended their practice in part because it was the only way to identify species that would otherwise remain unknown.

They distilled this into an adage: “What’s hit is history, what’s missed is mystery.”

In 18th-century New Mexico unbaptized Indians were often sold as domestic slaves. This was illegal, but the authorities accepted it on the theory that it “civilized” the slaves. In 1751, the wife of Alejandro Mora lodged a complaint in Bernalillo that her husband was treating their slave Juana inhumanely. The constable who investigated found Juana covered with bruises. Mora had broken her knees to keep her from running away and reopened the wounds periodically with a flintstone, so they were covered with festering ulcers. Her neck and body had been burned with live coals, and manacles had scabbed her ankles.

She said, “I have served my master for eight or nine years now but they have seemed more like 9,000 because I have not had one moment’s rest. He has martyred me with sticks, stones, whip, hunger, thirst, and burns all over my body. … He inflicted them saying that it was what the devil would do to me in hell, that he was simply doing what God had ordered him to do.”

Mora protested that he had only been looking out for Juana’s welfare. He had raped her only to test her claim of virginity, and he had hung her from a roof beam and beaten her only because she resisted him. The authorities removed her from Mora’s household, but he received not even a reprimand.

(Ramón A. Gutiérrez, Cuando Jesús llegó, las madres del maíz se fueron, 1991; Bernardo Gallegos, Postcolonial Indigenous Performances, 2017.)

Guillaume de Machaut’s Rondeau 14, from the 14th century, is a crab canon over a palindrome: When the singers reach the end of the line, the tenor (the lowest voice) reverses course and reads his music backward, and the other two voices follow suit, exchanging parts.

So they arrive where they started. De Machaut titled the piece “Ma fin est mon commencement” — “In my end is my beginning.”

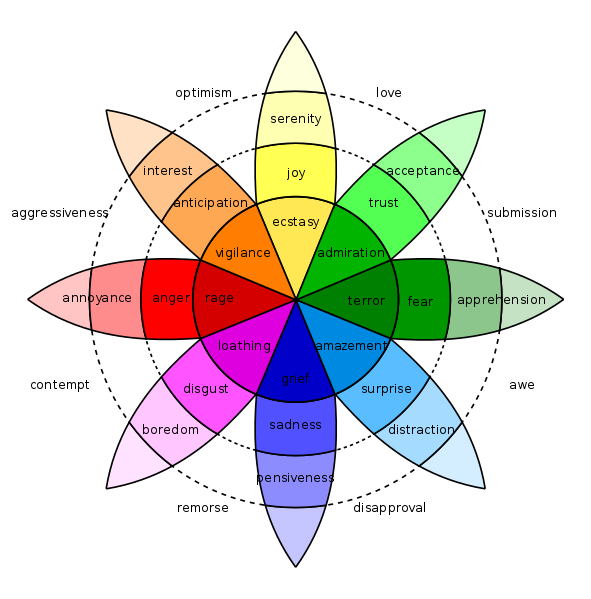

Three different Japanese texts of the early 19th century refer to a “hollow ship” that arrived on a local beach in 1803. A white-skinned young woman emerged, but fishermen found that she couldn’t communicate in Japanese, so they returned her to the vessel, which drifted back to sea.

This seems to be a folktale, though it’s an oddly specific one — the texts give specific dates (Feb. 22 or March 24) and give the dimensions of the craft (3.3 meters high, 5.4 meters wide), which was shaped like a rice pot or incense burner fitted with small windows. Reportedly the woman carried a small box that no one was allowed to touch.

But the place names mentioned appear to be fictitious; most likely the story is merely an expression of the insularity of the Edo period. One thing the ship wasn’t is a UFO — it never left the water, but simply floated away.

“There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there always has been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that ‘my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge.'” — Isaac Asimov, Newsweek, Jan. 21, 1980

In planning the lighting and atmosphere for Skull Island in 1933’s King Kong, animator Willis O’Brien relied heavily on Gustave Doré. In 1930 special effects expert Lewis W. Physioc had said, “If there is one man’s work that can be taken as the cinematographer’s text, it is that of Doré. His stories are told in our own language of ‘black and white,’ are highly imaginative and dramatic, and should stimulate anybody’s ideas.”

“The Doré influence is strikingly evident in the island scenes,” write Orville Goldner and George E. Turner in The Making of King Kong (1976) (click to enlarge). “Aside from the lighting effects, other elements of Dore illustrations are easily discernible. The affinity of the jungle clearings to those in Dore’s ‘The First Approach of the Serpent’ from Milton’s ‘Paradise Lost’ [left], ‘Dante in the Gloomy Wood’ from Dante’s ‘The Divine Comedy,’ ‘Approach to the Enchanted Palace’ from Perrault’s ‘Fairy Tales’ [right] and ‘Manz’ from Chateaubriand’s ‘Atala’ is readily apparent. The gorge and its log bridge bear more than a slight similarity to ‘The Two Goats’ from ‘The Fables’ of La Fontaine, while the lower region of the gorge may well have been designed after the pit in the Biblical illustration of ‘Daniel in the Lion’s Den.’ The wonderful scene in which Kong surveys his domain from the ‘balcony’ of his mountaintop home high above the claustrophobic jungles is suggestive of two superb Doré engravings, ‘Satan Overlooking Paradise’ from ‘Paradise Lost’ and ‘The Hermit on the Mountain’ from ‘Atala.'”

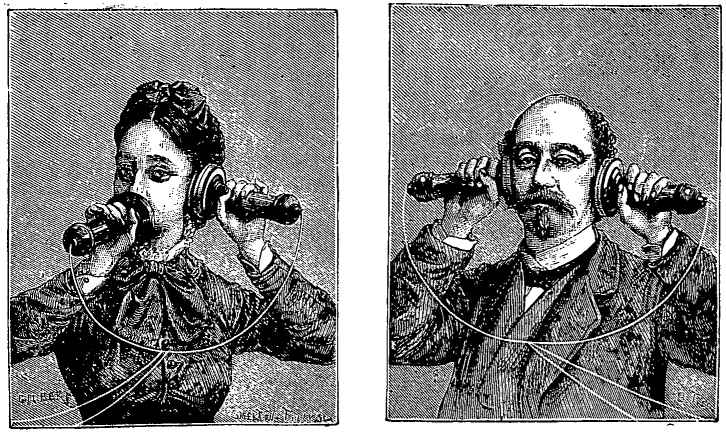

telepheme

n. a telephone message

telelogue

n. a conversation on the telephone