In 1934 Ole Kirk Kristiansen named his toy company Lego, after the Danish phrase for “play well” (leg godt).

He found out later that it also means “I put together” in Latin.

In 1934 Ole Kirk Kristiansen named his toy company Lego, after the Danish phrase for “play well” (leg godt).

He found out later that it also means “I put together” in Latin.

For his keynote address at the 1998 ACM OOPSLA conference, Sun Microsystems computer scientist Guy Steele illustrated the value of growing a computer language by growing the language of his talk itself, starting with words of one syllable and using these to build new definitions that permit increasing sophistication.

“For this talk, I chose to take as my primitives all the words of one syllable, and no more, from the language I use for most of my speech each day, which is called English. My firm rule for this talk is that if I need to use a word of two or more syllables, I must first define it.”

(Via MetaFilter.)

Strangely, Professor Moriarty and his brother have the same name.

Sherlock Holmes mentions his nemesis seven times in “The Final Problem,” but always as “Professor Moriarty” — he gives no first name (“My dear Watson, Professor Moriarty is not a man who lets the grass grow under his feet”).

But at one point Watson refers to “the recent letters in which Colonel James Moriarty defends the memory of his brother,” who was killed after his dramatic struggle with Holmes atop the Reichenbach Falls.

But in “The Adventure of the Empty House,” Holmes remarks to Watson, “[I]f I remember right, you had not heard the name of Professor James Moriarty, who had one of the great brains of the century.”

So “the Napoleon of crime” and his brother are both named James, it appears. One explanation that’s been suggested is that “James Moriarty” is a compound surname — in which case the first name of each man remains a mystery.

In 1947 Theodor Adorno devised a test to measure the authoritarian personality — he called it the F-scale, because it was intended to measure a person’s potential for fascist sympathies:

Adorno hoped that making the questions oblique would encourage participants to reveal their candid feelings, “for precisely here may lie the individual’s potential for democratic or antidemocratic thought and action in crucial situations.”

“The F-scale … was adopted by quite a few experimental psychologists and sociologists, and remained in the repertoire of the social sciences well into the 1960s,” writes Evan Kindley in Questionnaire (2016). But it’s been widely criticized — Adorno and his colleagues assumed that any attraction to fascist ideas was pathological; the statements were worded so that agreement always indicated an authoritarian response; and people with high intelligence tended to see through the “indirect” items anyway.

Ironically, the test’s dubious validity might be a good thing, Kindley notes: Otherwise, “If something like the F-scale were to fall into the wrong hands, couldn’t it become a vehicle of tyranny?”

In his 1869 French rendering of Alice in Wonderland, Henri Bué found a uniquely felicitous way to translate a pun. Here’s the original:

‘If everybody minded their own business,’ the Duchess said in a hoarse growl, ‘the world would go round a deal faster than it does.’

‘Which would not be an advantage,’ said Alice … ‘Just think what work it would make with the day and night! You see the earth takes twenty-four hours to turn round on its axis –‘

‘Talking of axes,’ said the Duchess, ‘chop off her head.’

Bué couldn’t reproduce the pun using the French word for ax (hache), but he came up with this:

‘Si chacun s’occupait de ses affaires,’ dit la Duchesse avec un grognement rauque, ‘le mond n’en irait que mieux.’

‘Ce qui ne serait guère avantageux,’ dit Alice … ‘Songez à ce que deviendraient le jour et la nuit; vous voyez bien, la terre met vingt-quatre heures à faire sa révolution.’

‘Ah! vous parlez de faire des révolutions!’ dit la Duchesse. ‘Qu’on lui coupe la tête!’

In The Astonishment of Words, Victor Proetz writes, “Here Bué — with a stroke of wizardry and judgment which, in this instance, is not translation by word, but translation by change of word — has instantaneously transformed a witty English idea in its entirety into a perfectly parallel, equally witty French idea. And when ‘the Duchess’ changes into ‘la Duchesse,’ the axe, by association, becomes a guillotine.”

Lunching at Stephen Spenders’ in 1946, T.S. Eliot admired his host’s transparent cigarette case. Spender sent it to him with this verse:

When those aged eagle eyes which look

Through human flesh as through a book,

Swivel an instant from the page

To ignite the luminous image

With the match that lights his smoke —

Then let the case be transparent

And let the cigarettes, apparent

To his x-ray vision, lie

As clear as rhyme and image to his eye.

Eliot responded:

The sudden unexpected gift

Is more precious in the eyes

Than the ordinary prize

Of slow approach or movement swift.

While the cigarette is whiffed

And the tapping finger plies

Here upon the table lies

The fair transparency. I lift

The eyelids of the aging owl

At twenty minutes to eleven

Wednesday evening (summer time)

To salute the younger fowl

With this feeble halting rhyme

The kind, the admirable Stephen.

In studying the relationship between brain function and language, University of Alberta psychologist Chris Westbury found that people agree nearly unanimously as to the funniness of nonsense words. Some of the words predicted to be most humorous in his study:

howaymb, quingel, finglam, himumma, probble, proffin, prounds, prothly, dockles, compide, mervirs, throvic, betwerv

It seems that the less statistically likely a collection of letters is to form a real word in English, the funnier it strikes us. Why should that be? Possibly laughter signals to ourselves and others that we’ve recognized that something is amiss but that it’s not a danger to our safety.

(Chris Westbury et al., “Telling the World’s Least Funny Jokes: On the Quantification of Humor as Entropy,” Journal of Memory and Language 86 [2016], 141–156.)

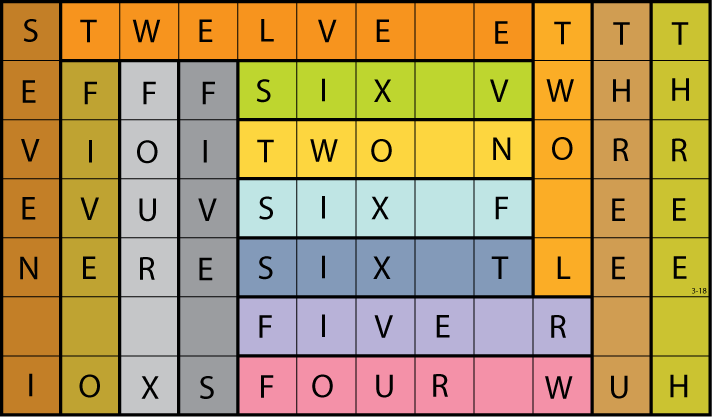

Lee Sallows sent this self-descriptive rectangle tiling: The grid catalogs its own contents by arranging its 70 letters and 14 spaces into 14 itemizing phrases.

Bonus: The rectangle measures 7 × 12, which is commemorated by the two strips that meet in the top left-hand corner. And “The author’s signature is also incorporated.”

(Thanks, Lee!)

Writing in the Territorial Enterprise in 1863, Mark Twain claimed to have found the following letter atop Sugarloaf Peak, Nevada. It was addressed to Miss Mary Links of Virginia City from Solon Lycurgus, “law student, and notary public in and for the said County of Storey, and Territory of Nevada”:

To the loveliness to whom these presents shall come, greeting:–This is a lovely day, my own Mary; its unencumbered sunshine reminds me of your happy face, and in the imagination the same doth now appear before me. Such sights and scenes as this ever remind me, the party of the second part, of you, my Mary, the peerless party of the first part. The view from the lonely and segregated mountain peak, of this portion of what is called and known as Creation, with all and singular the hereditaments and appurtenances thereunto appertaining and belonging, is inexpressively grand and inspiring; and I gaze, and gaze, while my soul is filled with holy delight, and my heart expands to receive thy spirit-presence, as aforesaid. Above me is the glory of the sun; around him float the messenger clouds, ready alike to bless the earth with gentle rain, or visit it with lightning, and thunder, and destruction; far below the said sun and the messenger clouds aforesaid, lying prone upon the earth in the verge of the distant horizon, like the burnished shield of a giant, mine eyes behold a lake, which is described and set forth in maps as the Sink of Carson; nearer, in the great plain, I see the Desert, spread abroad like the mantle of a Colossus, glowing by turns, with the warm light of the sun, hereinbefore mentioned, or darkly shaded by the messenger clouds aforesaid; flowing at right angles with said Desert, and adjacent thereto, I see the silver and sinuous thread of the river, commonly called Carson, which winds its tortuous course through the softly tinted valley, and disappears amid the gorges of the bleak and snowy mountains — a simile of man! — leaving the pleasant valley of Peace and Virtue to wander among the dark defiles of Sin, beyond the jurisdiction of the kindly beaming sun aforesaid! And about said sun, and the said clouds, and around the said mountains, and over the plain and the river aforesaid, there floats a purple glory — a yellow mist — as airy and beautiful as the bridal veil of a princess, about to be wedded according to the rites and ceremonies pertaining to, and established by, the laws or edicts of the kingdom or principality wherein she doth reside, and whereof she hath been and doth continue to be, a lawful sovereign or subject. Ah! my Mary, it is sublime! it is lovely! I have declared and made known, and by these presents do declare and make known unto you, that the view from Sugar Loaf Peak, as hereinbefore described and set forth, is the loveliest picture with which the hand of the Creator has adorned the earth, according to the best of my knowledge and belief, so help me God.

Given under my hand, and in the spirit-presence of the bright being whose love has restored the light of hope to a soul once groping in the darkness of despair, on the day and year first above written.

(Signed) Solon Lycurgus