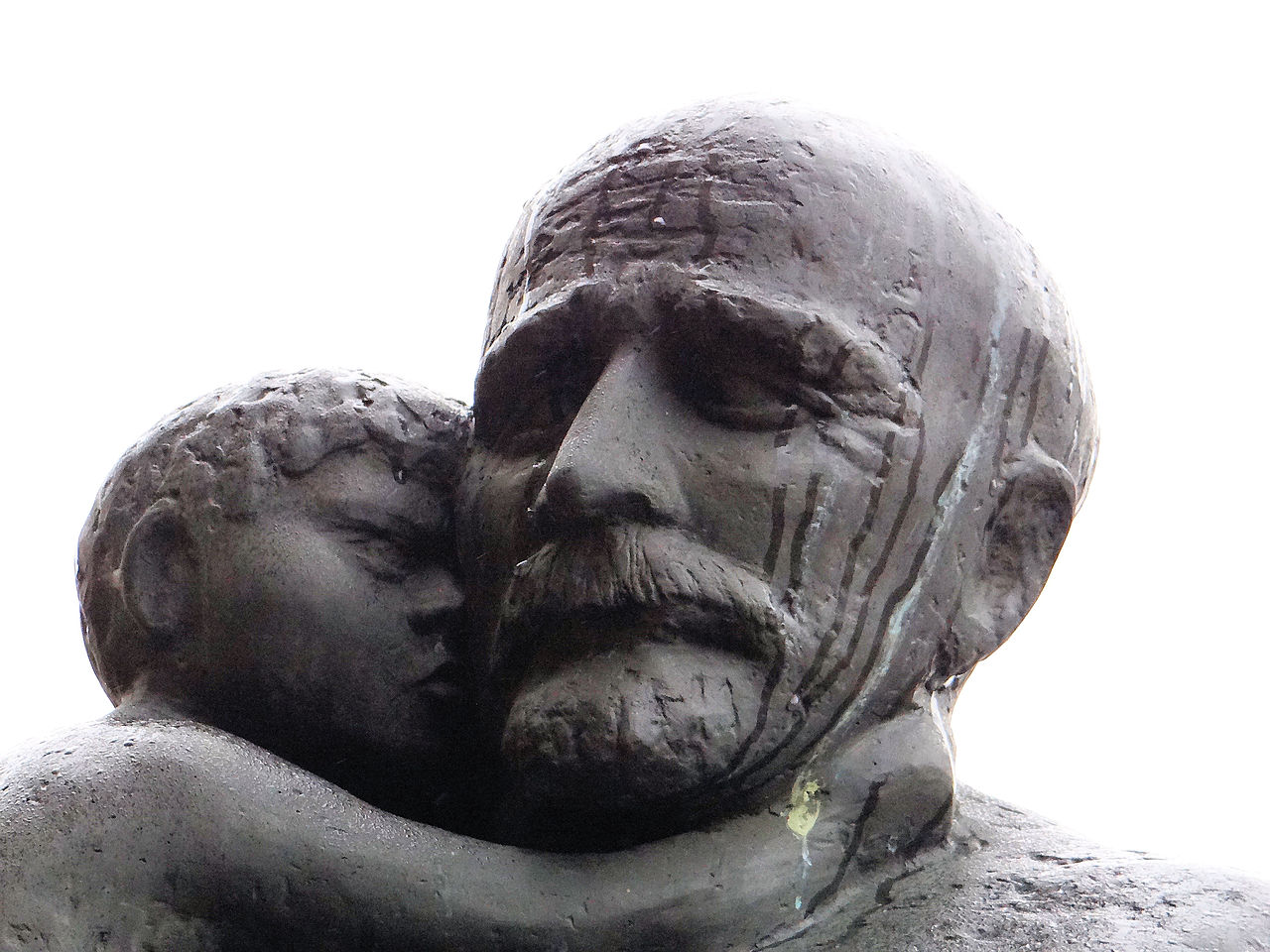

Polish educator Janusz Korczak set out to remake the world just as it was falling apart. In the 1930s his Warsaw orphanage was an enlightened society run by the children themselves, but he struggled to keep that ideal alive as Europe descended into darkness. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll tell the story of the children’s champion and his sacrifices for the orphans he loved.

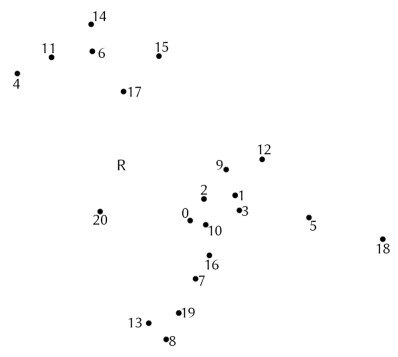

We’ll also visit an incoherent space station and puzzle over why one woman needs two cars.