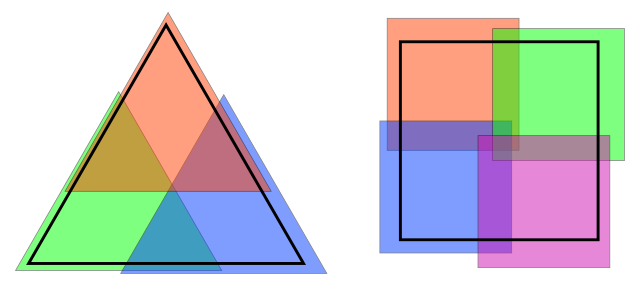

A triangle can be covered by three smaller copies of itself. A square requires four smaller copies. But in general four will do: Any bounded convex set in the plane can be covered with four smaller copies of itself (and in fact the fourth copy is needed only in the case of parallelograms, like the square).

Is this true in every dimension? In 1957 Swiss mathematician Hugo Hadwiger conjectured that every n-dimensional convex body can be covered by 2n smaller copies of itself. But this remains an unsolved problem.

(Interestingly, Russian mathematician Vladimir Boltyansky showed that this problem is equivalent to one of illumination: How many floodlights does it take to illuminate an opaque convex body from the exterior? The number of floodlights turns out to equal the number of smaller copies needed to cover the body.)