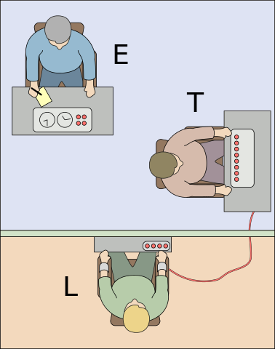

In the famous “Milgram experiment” at Yale in 1961, an experimenter directed each subject (the “teacher”) to give what she believed were increasingly painful electric shocks to an unseen “learner” (really an actor). Psychologist Stanley Milgram found that a surprisingly high proportion of the subjects would obey the experimenter’s instructions, even over the learner’s shouts and protests, to the point where the learner fell silent.

Milgram wrote, “For the teacher, the situation quickly becomes one of gripping tension. It is not a game for him: conflict is intense. The manifest suffering of the learner presses him to quit: but each time he hesitates to administer a shock, the experimenter orders him to continue. To extricate himself from this plight, the subject must make a clear break with authority.”

As it happened, one participant, Gretchen Brandt, had been a young girl coming of age in Germany during Hitler’s rise to power and repeatedly exposed to Nazi propaganda during her childhood. During Milgram’s experiment, when the learner began to complain about a “heart condition,” she asked the experimenter, “Shall I continue?” After administering what she thought was 210 volts, she said, “Well, I’m sorry, I don’t think we should continue.”

Experimenter: The experiment requires that you go on until he has learned all the word pairs correctly.

Brandt: He has a heart condition, I’m sorry. He told you that before.

Experimenter: The shocks may be painful but they’re not dangerous.

Brandt: Well, I’m sorry. I think when shocks continue like this they are dangerous. You ask him if he wants to get out. It’s his free will.

Experimenter: It is absolutely essential that we continue.

Brandt: I’d like you to ask him. We came here of our free will. If he wants to continue I’ll go ahead. He told you he had a heart condition. I’m sorry. I don’t want to be responsible for anything happening to him. I wouldn’t like it for me either.

Experimenter: You have no other choice.

Brandt: I think we are here on our own free will. I don’t want to be responsible if anything happens to him. Please understand that.

She refused to continue, and the experiment ended. Milgram wrote, “The woman’s straightforward, courteous behavior in the experiment, lack of tension, and total control of her own action seem to make disobedience a simple and rational deed. Her behavior is the very embodiment of what I envisioned would be true for almost all subjects.”

Asked afterward how her experience as a youth might have influenced her, Brandt said slowly, “Perhaps we have seen too much pain.”

(From Thomas Heinzen and Wind Goodfriend, Case Studies in Social Psychology, 2019.)