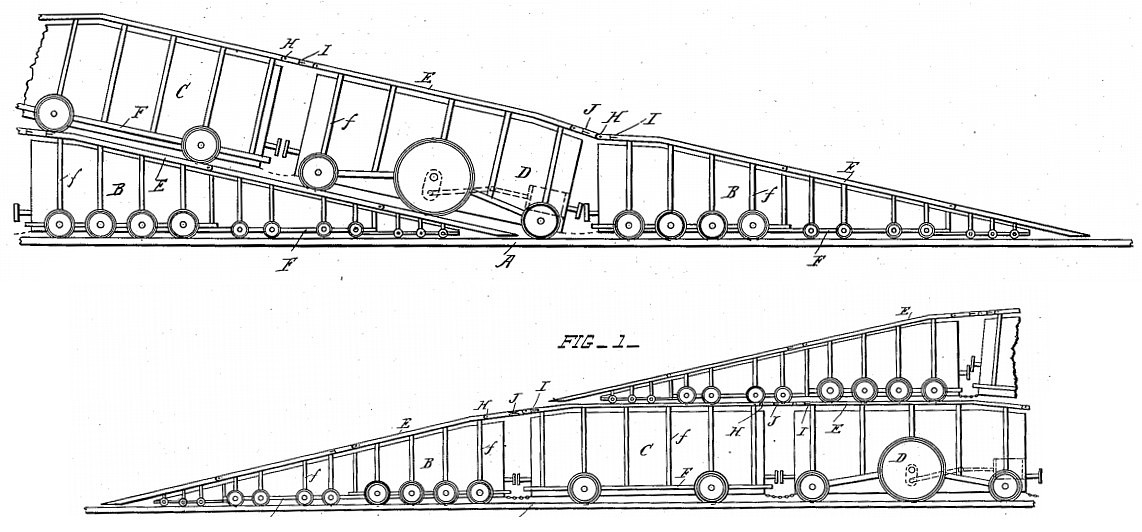

In 2009 I mentioned that in 1895 Henry Simmons invented ramp-shaped railroad cars that could pass over one another.

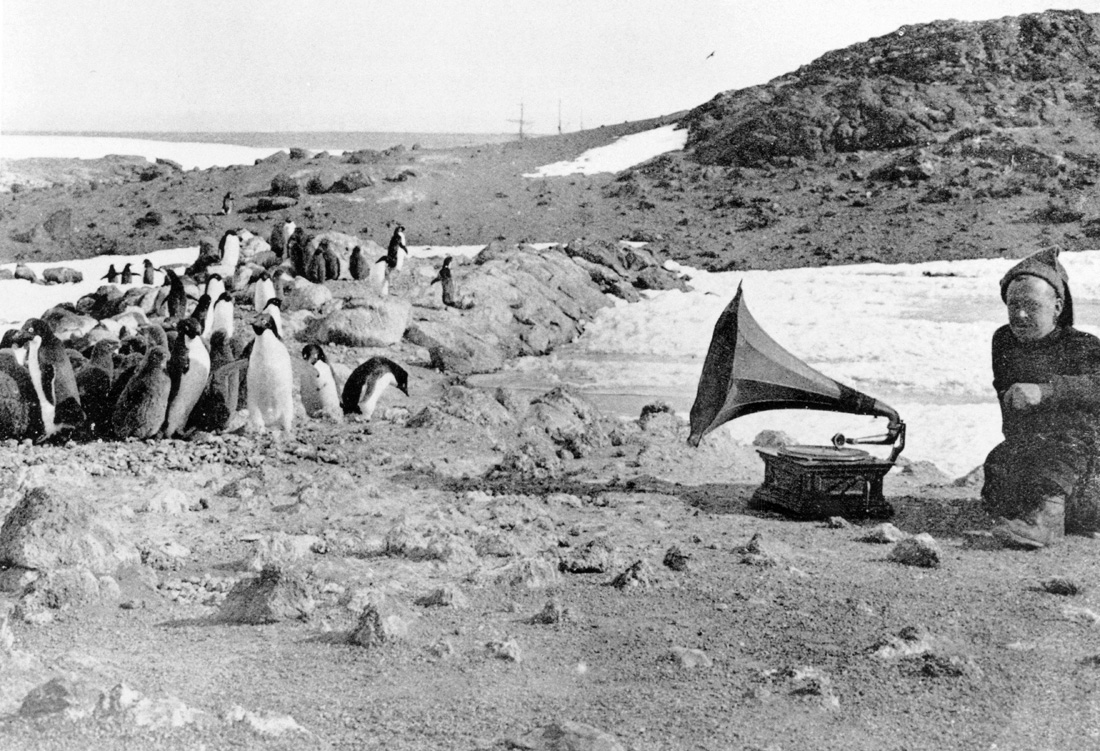

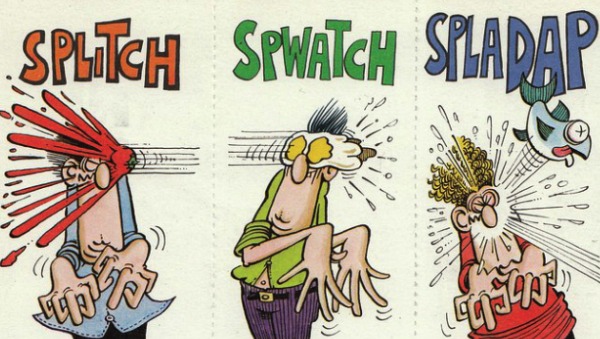

At the time I thought this was alarming, but something like it was actually carried out. On Coney Island’s Leap Frog Railway of 1905, one car full of passengers clambered over another:

The passengers in breathless excitement momentarily anticipating disaster, realizing that their lives are in jeopardy, clinging to one another for safety, closing their eyes to the impending danger. … The cars crash into one another, 32 people are hurled over the heads of 32 others. … They are suddenly awakened to a realization of the fact that they have actually collided with another car and yet they find themselves safe and sound … proceeding in the same direction in which they started.

On the return journey the cars changed positions. At the time this was billed as a prototype “to reduce the mortality rate due to collisions on railways.” Now I wonder whether Simmons’ invention was ever realized.

(From Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York, 1994.)