A problem from the 2011 Moscow Mathematical Olympiad: In a certain square matrix, the sum of the two largest numbers in each row is r and the sum of the two largest in each column is c. Show that r = c.

Unquote

“It is a well-known fact, too, that in the ancient world in which the entire population were non-smokers, crime of the most horrid type was rampant. It was a non-smoker who committed the first sin and brought death into the world and all our woe. Nero was a non-smoker. Lady Macbeth was a non-smoker. Decidedly, the record of the non-smokers leaves them little to be proud of.” — Robert Lynd

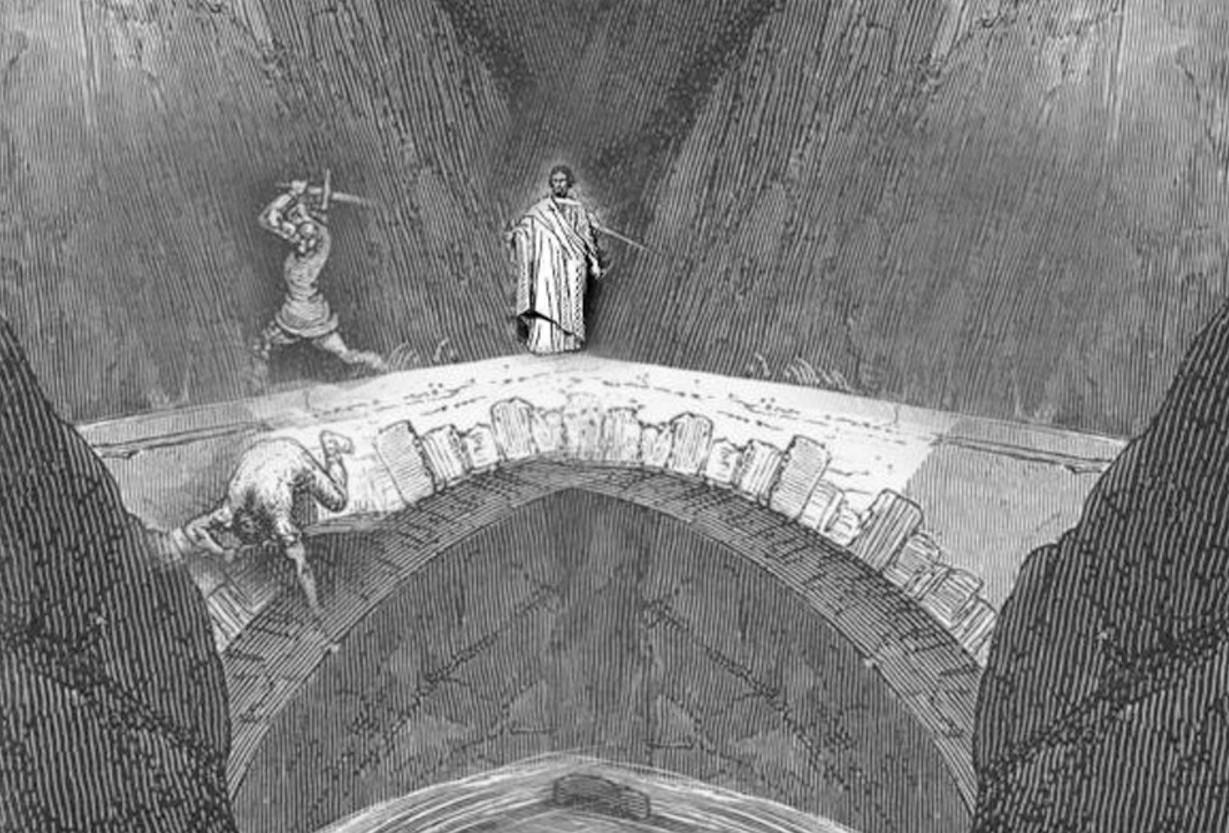

The Bell Tolls

John Donne may have posed for his own funerary monument. In his Lives of 1658, Izaak Walton writes:

… Dr. Donne sent for a Carver to make for him in wood the figure of an Urn, giving him directions for the compass and height of it; and, to bring with it a board of the height of his body. These being got, then without delay a choice Painter was to be in a readiness to draw his picture, which was taken as followeth. — Several Charcole-fires being first made in his large Study, he brought with him into that place his winding-sheet in his hand; and, having put off all his cloaths, had this sheet put on him, and so tyed with knots at his head and feet, and his hands so placed, as dead bodies are usually fitted to be shrowded and put into the grave. Upon this Urn he thus stood with his eyes shut, and with so much of the sheet turned aside as might shew his lean, pale, and death-like face; which was purposely turned toward the East, from whence he expected the second coming of his and our Saviour. Thus he was drawn at his just height; and when the picture was fully finished, he caused it to be set by his bed-side, where it continued, and became his hourly object till his death …”

It’s not clear whether this really happened — the sketch, if there was one, has been lost. The statue stands in St. Paul’s Churchyard in London.

Transparency

There is writing which resembles the mosaics of glass you see in stained-glass windows. Such windows are beautiful in themselves and let in the light in colored fragments, but you can’t expect to see through them. In the same way, there is poetic writing that is beautiful in itself and can easily affect the emotions, but such writing can be dense and can make for hard reading if you are trying to figure out what’s happening.

Plate glass, on the other hand, has no beauty of its own. Ideally, you ought not to be able to see it at all, but through it you can see all that is happening outside. That is the equivalent of writing that is plain and unadorned. Ideally, in reading such writing, you are not even aware that you are reading. Ideas and events seem merely to flow from the mind of the writer into that of the reader without any barrier between.

— Isaac Asimov, I. Asimov: A Memoir, 1994

Elsewhere he wrote, “There is a great deal of art to creating something that seems artless.”

Otherwise Stated

Another exercise in linguistic purism: In his 1989 essay “Uncleftish Beholding,” Poul Anderson tries to explain atomic theory using Germanic words almost exclusively, coining terms of his own as needed:

The firststuffs have their being as motes called unclefts. These are mightly small; one seedweight of waterstuff holds a tale of them like unto two followed by twenty-two naughts. Most unclefts link together to make what are called bulkbits. Thus, the waterstuff bulkbit bestands of two waterstuff unclefts, the sourstuff bulkbit of two sourstuff unclefts, and so on. (Some kinds, such as sunstuff, keep alone; others, such as iron, cling together in ices when in the fast standing; and there are yet more yokeways.) When unlike clefts link in a bulkbit, they make bindings. Thus, water is a binding of two waterstuff unclefts with one sourstuff uncleft, while a bulkbit of one of the forestuffs making up flesh may have a thousand thousand or more unclefts of these two firststuffs together with coalstuff and chokestuff.

Reader Justin Hilyard, who let me know about this, adds, “This sort of not-quite-conlang is still indulged in now and then today; it’s often known as ‘Anglish’, after a coining by British humorist Paul Jennings in 1966, in a three-part series in Punch magazine celebrating the 900th anniversary of the Norman conquest. He also wrote some passages directly inspired by William Barnes in that same Germanic-only style.”

Somewhat related: In 1936 Buckminster Fuller explained Einstein’s theory of relativity in a 264-word telegram.

(Thanks, Justin.)

An “Excentrical Query”

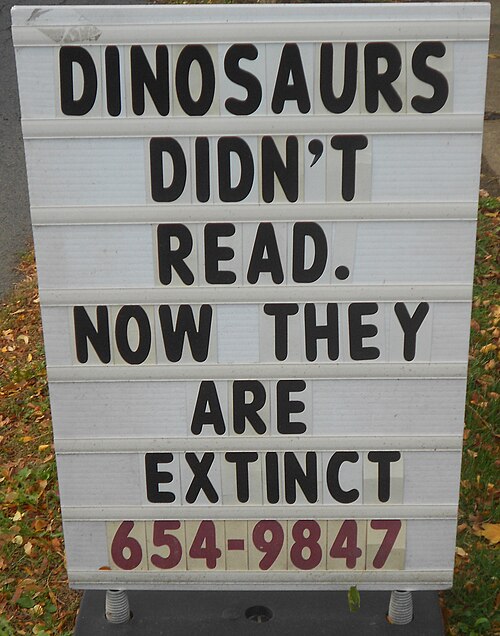

Noted

Sign outside the public library at West Pittston, Pa., October 2016:

In Other Words

In the 19th century, British polymath William Barnes tried to reform English by limiting it to words of Saxon-English origin. Where no “Teutonic” words were available to express his meaning, he made up alternatives, such as sky-sill for horizon, glee-craft for music, wort-lore for botany, hearsomeness for obedience, somely for plural, and folkwain for omnibus.

In 1948, Richard Lister challenged the readers of the New Statesman to write the opening paragraphs of a novel set in present-day London in this style of reformed English. Reader D.M. Low offered this:

As Ernest was wafted up on the dredger from the thorough-hole at Kingsway he was inwardly upborne to see Pearl again; but, alas, evenly castdown for the blue-eyed bebrilled booklearner was floating downwards on the other ladderway. It was now or never. Ernest fought back against the rising stairs and the gainbuildfulness of hirelings bound for work. Pushing aside fingerwriters, shophelpers and even deeded reckoning-keepers, by an overmanly try he reached the bottom eventimeously with Pearl.

‘What luck! Can you eat with me tonight? I know a fair little upstaker near here.’

‘Oh! I can’t. My Between-go is in Fogmonth, and I must get through and …’

The rumble of the ambercrafty wagonsnake drowned her words.

‘Hark! There’s the tug. I must fly.’

It was hard to be wisdomlustful. Forlorn in his trystlessness Ernest sought Kingsway again and dodging hire-shiners and other self-shifters recklessly headed towards the worldheadtownly manystreakiness of the Strand.

He appended this glossary:

dredger: escalator.

ladderway: escalator.

upborne: elated.

evenly: equally.

bebrilled: bespectacled, (German Brille).

booklearner: student.

gainbuildfulness: obstructiveness.

fingerwriters: typists, cf. dattilografa.

deeded reckoning keepers: chartered accountants.

overmanly: superhuman.

eventimeously: simultaneously.

upstaker (less correctly upstoker): restaurant.

Between go: student slang for Between while try out i.e., Intermediate Examination.

Fogmonth: November.

ambercrafty: electric, lit. electric powered.

wagonsnake: train (archaic and poet.).

tug: train cf. German Zug.

wisdomlustful: philosophical.

trystlessness: disappointment.

hire-shiners: taxis.

self-shifters: automobiles.

manystreakiness: variety.

worldheadtownly: cosmopolitan.

Other readers had suggested eyebiting for attractive, lip-hair for moustache, slidehorn for trombone, and smokeweed for cigarette. The winning entries are here.

Buridan’s Bridge

Socrates wants to cross a river and comes to a bridge guarded by Plato. The two speak as follows:

Plato: ‘Socrates, if in the first proposition which you utter, you speak the truth, I will permit you to cross. But surely, if you speak falsely, I shall throw you into the water.’

Socrates: ‘You will throw me into the water.’

Jean Buridan posed this conundrum in his Sophismata in the 14th century. Like a similar paradox in Don Quixote, it seems to leave the guardian in an impossible position — whether Socrates speaks truly or falsely, it would seem, the promise cannot be fulfilled.

Some readers offered a wry solution: Wait until he’s crossed the bridge, and then throw him in.

Watch This Space

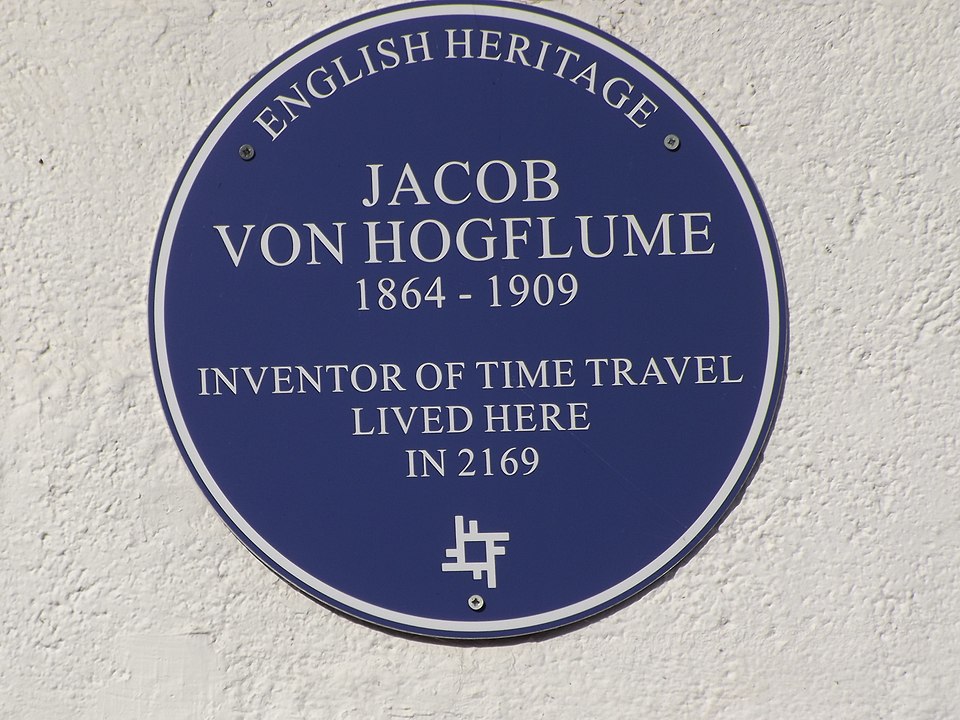

Another blue plaque, this one in Long Itchington, October 2014:

Related: Riverside, Iowa, is already congratulating itself as the future birthplace of James T. Kirk.