In What a Word!, his 1936 examination of English usage, A.P. Herbert takes up a letter written in “officese”:

Madam,

We are in receipt of your favour of the 9th inst. with regard to the estimate required for the removal of your furniture and effects from the above address to Burbleton, and will arrange for a Representative to call to make an inspection on Tuesday next, the 14th inst., before 12 noon, which we trust will be convenient, after which our quotation will at once issue.

He reduces this to:

Madam,

We have your letter of May 9th requesting an estimate for the removal of your furniture and effects to Burbleton, and a man will call to see them next Tuesday forenoon if convenient, after which we will send the estimate without delay.

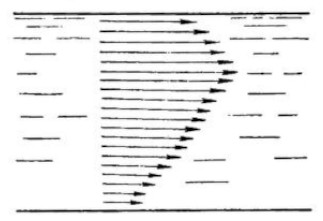

This shortens the letter from 66 words to 42. Then he cuts it again, to 35 words, or 157 letters against the original 294, a savings of nearly 50 percent:

Madam,

Thank you for your letter of May 9th. A man will call next Tuesday, forenoon, to see your furniture and effects, after which, without delay, we will send our estimate for their removal to Burbleton.

In a large firm, he estimates, cutting “verbose and indolent, obscure, inelegant, and time-devouring monkey-talk” could save a week’s work for two typists.

Elsewhere he considers a memo that reads “Hot-Water Bottles: With reference to the above matter I should like an opportunity of discussing same with you.” The improvement he suggests is “Could we, please, have a talk about Hot-Water Bottles?”