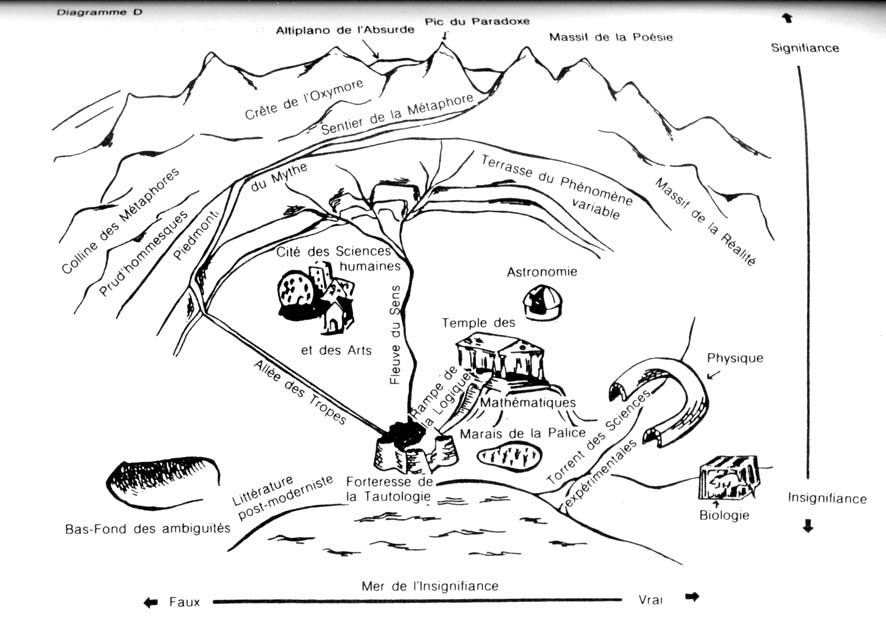

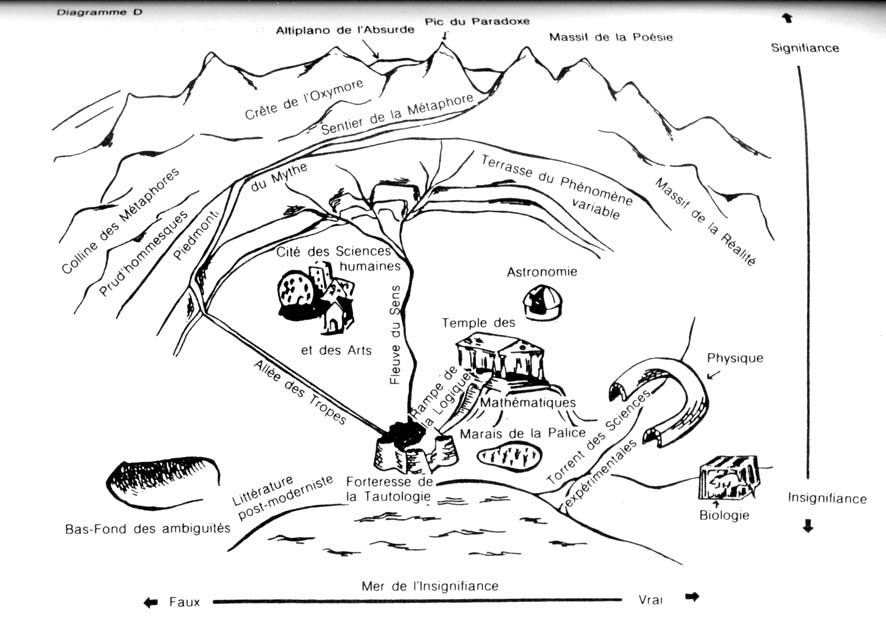

In To Predict Is Not to Explain, mathematician René Thom describes a lunch at which psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan responded strongly to his statement that “Truth is not limited by falsity, but by insignificance.” Thom described the idea later in a drawing:

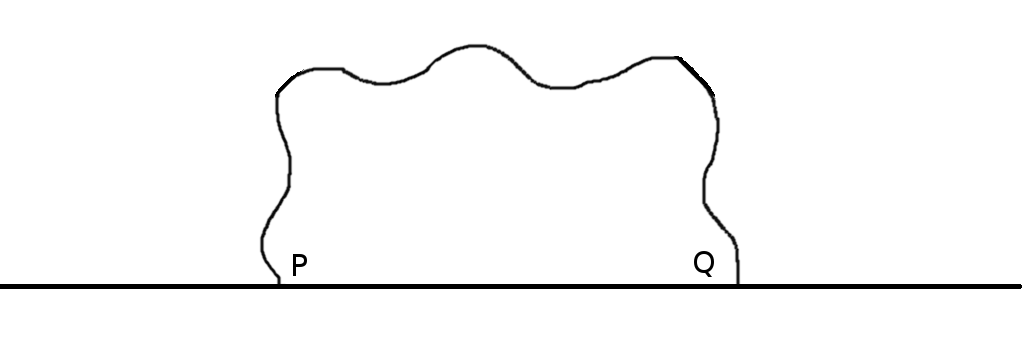

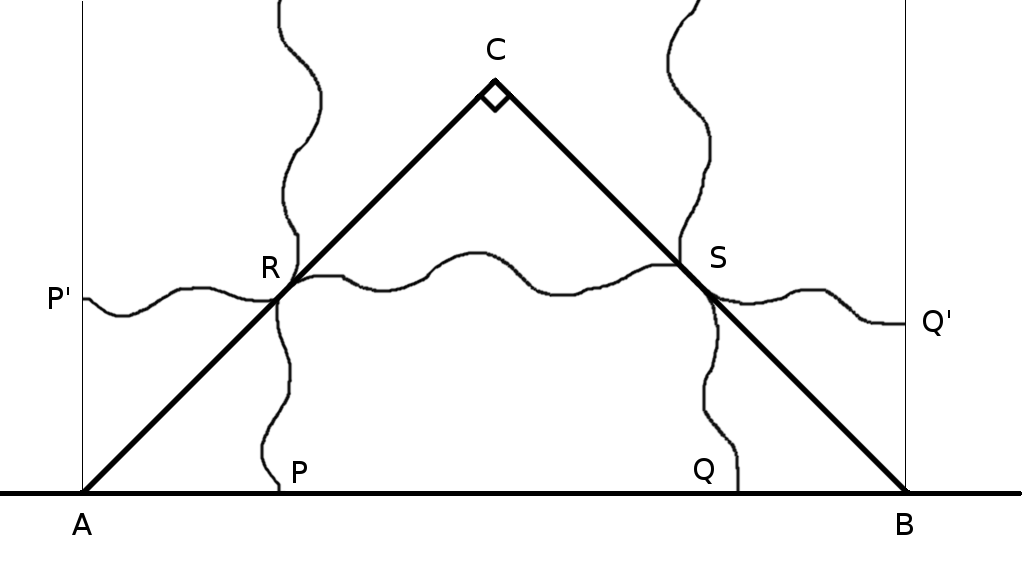

At the base, one finds an ocean, the Sea of the Insignificance. On the continent, Truth is on one side, Falsehood on the other. They are separated by a river, the River of Discernment. It is indeed the faculty of discernment that separates truth from falsehood. It’s Aristotle’s notion: the capacity for contradiction. It’s what separates us from animals: When information is received by them, it’s instantly accepted and it triggers obedience to its message. Human beings, however, have the capacity to withdraw and to question its veracity.

Following the banks of this river, which flows into the Sea of Insignificance, one travels along a coastline that is slightly concave: Situated at one end is the Slough of Ambiguity; at the other end is the Swamp of La Palice. At the head of the river delta, one sees the Stronghold of Tautology: That’s the stronghold of the logicians. One climbs a rampart towards a small temple, a kind of Parthenon: that’s Mathematics.

To the right, one finds the Exact Sciences: Up in the mountains that surround the bay is Astronomy, with an observatory topping its temple; at the far right stand the giant machines of Physics, the accelerator rings at CERN; the animals in their cages indicate the laboratories of Biology. Out of all this, there emerges a creek that feeds into the Torrent of Experimental Science, which flows into the Sea of Insignificance.

To the left is a wide path climbing towards the north west, up to the City of Human Arts and Sciences. Continuing along it one comes to the foothills of Myth. We’ve entered the kingdom of anthropology. Up at the top is the High Plateau of the Absurd. The spine signifies the loss of the ability to discern contraries, something like an excess of universal understanding which makes life impossible.

He explains the central idea in more detail starting on page 173 of the PDF linked above. “It’s something I’ve done to amuse myself, but it reflects something real, I think: The Logos, the possibility of representation by language, only comes into play for humanity in a rather limited number of situations … [O]ne begins to manufacture linguistic entities which do not correspond to real things. … That’s where the River of Discernment runs into the Fortress of Tautology, into the sewers. It’s become invisible, but at the surface it can smell pretty bad.”