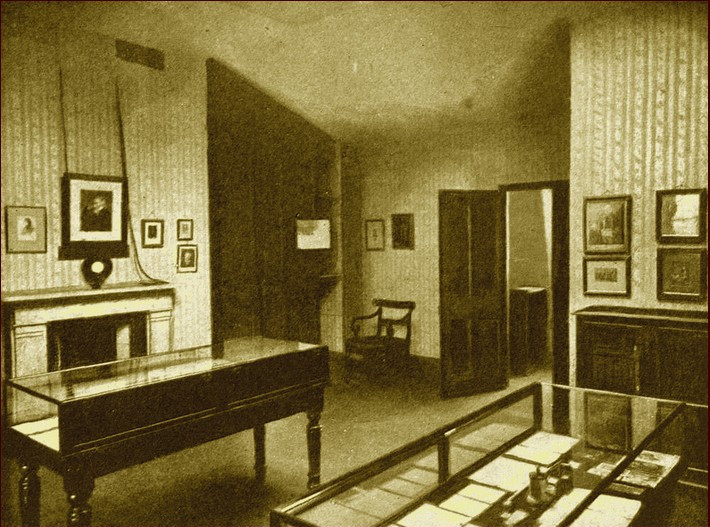

Thomas Carlyle required absolute silence to write, and silence was hard to come by in London’s Chelsea district, where he struggled to compose his biography of Frederick the Great. His wife, Jane, postponed her cleaning until Thomas was away and perpetually tried to quiet neighborhood dogs, roosters, and street vendors. But it wasn’t enough.

In 1853 Carlyle wrote to his sister: “At length, after deep deliberation, I have fairly decided to have a top story put upon the house, one big apartment, twenty feet square, with thin double walls, light from the top, etc., and artfully ventilated, into which no sound can come; and all the cocks in nature may crow round it without my hearing a whisper of them!”

Alas, the skylight wasn’t soundproof, and he was assailed by railway whistles, church bells, and steamer sirens from the Thames. Jane wrote, “The silent room is the noisiest room in the house, and Mr. Carlyle is very much out of sorts.” He finished the biography, finally, but he called it “the Nightmare … the Minotaur … the Unutterable book.”