A calculator made of roller coasters, devised by Marcel Vos using Rollercoaster Tycoon 2.

He explains it in this Imgur album.

A calculator made of roller coasters, devised by Marcel Vos using Rollercoaster Tycoon 2.

He explains it in this Imgur album.

Driving on a highway in 1977, Belgian experimental psychologist Jozef Nuttin noticed that he preferred license plates containing letters from his own name. In testing this idea, he found that it’s generally so: People prefer letters belonging to their own first and last names over other letters, and this seems to be true across letters and languages.

Nuttin found this so surprising that he withheld his results for seven years before going public. (A colleague at his own university called it “so strange that a down-to-earth researcher will spontaneously think of an artifact.”) But it’s since been replicated in dozens of studies in 15 countries and using four different alphabets. When subjects are asked to name a preference among letters, on average they consistently like the letters in their own name best.

(The reason seems to be related to self-esteem. People prefer things associated with the self — for example, they tend to favor the number reflecting the day of the month on which they were born. People who don’t like themselves tend not to exhibit the name-letter effect.)

(Jozef M. Nuttin Jr., “Narcissism Beyond Gestalt and Awareness: The Name Letter Effect,” European Journal of Social Psychology 15:3 [September 1985], 353-361. See Initial Velocity.)

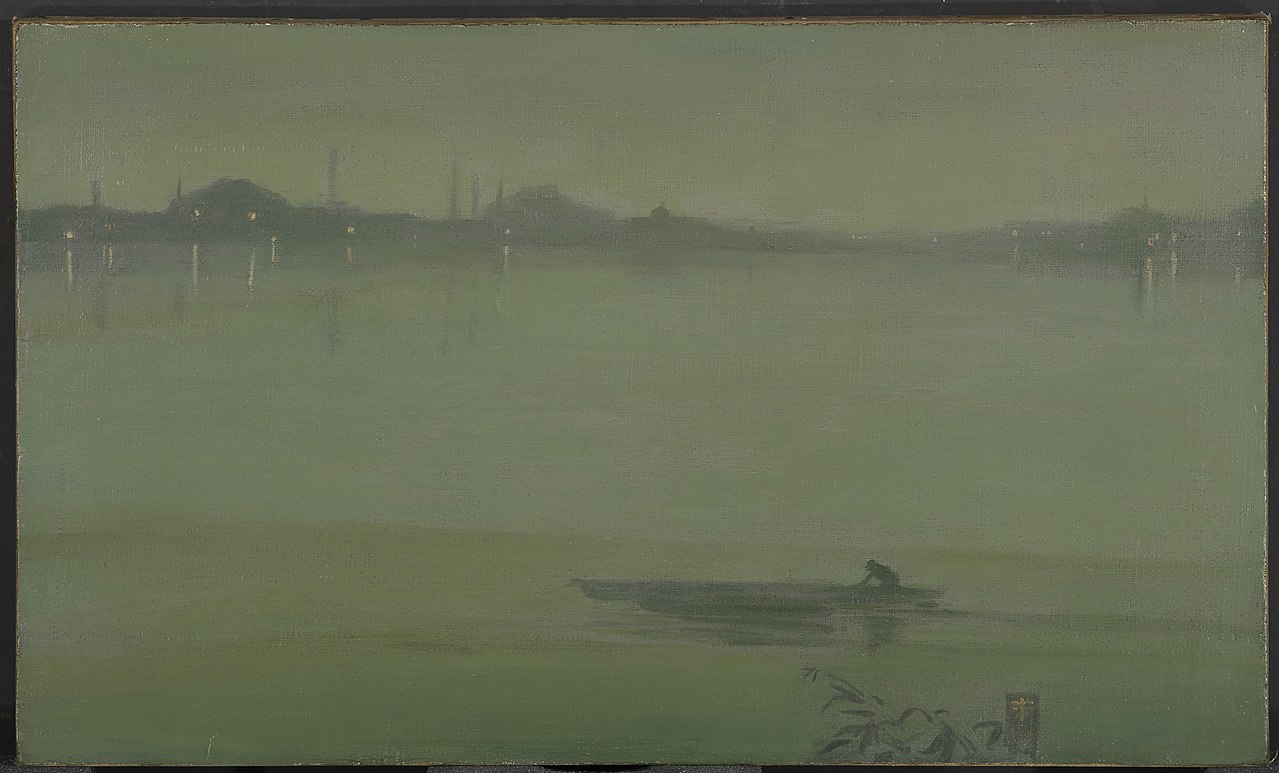

A woman told James McNeill Whistler that the view of the Thames she had just seen reminded her exactly of his series of paintings.

He told her, “Yes, madam. Nature is creeping up.”

In July 1996 a family of four set out from Dresden for a holiday in the American Southwest. Architect Egbert Rimkus, 34, his son Georg, 11, his girlfriend Cornelia Meyer, 27, and her son Max, 4, arrived in Los Angeles and visited Las Vegas, then traveled to Death Valley National Park. Their names appear in the logs of several visitor sites, and it appears they spent their first night camping in a canyon near Telescope Peak.

When they failed to return as planned on July 29, Rimkus’s ex-wife began to make inquiries. When their travel agency learned that the rented van had not been returned, it notified Interpol. Temperatures in the park had topped 120 degrees on the week of the disappearance.

In late October, a helicopter search pilot spotted the van on a closed road in a remote part of the park known as Anvil Canyon. It had been driven at least 200 miles, and the tracks showed that it had run on flat tires and bent wheels for the final two miles. More than 200 search and rescue workers combed the area; under a bush a quarter mile away they found a beer bottle that appeared to have come from a package in the van.

The search was called off on Oct. 26, but 13 years later, in 2009, hikers discovered the skeletal remains of a man and a woman several miles south of that spot, near a photo ID belonging to Cornelia. Authorities said they were fairly sure the bones belonged to Egbert and Cornelia, but the remains of the children have never been found.

(Thanks, Tom.)

J.H. Thomas: I’ve got a ‘orrible ‘eadache.

F.E. Smith: What you need is a couple of aspirates.

In 1726 London was rocked by a bizarre sensation: A local peasant woman began giving birth to rabbits, astounding the city and baffling the medical community. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll review the strange case of Mary Toft, which has been called “history’s most fascinating medical mystery.”

We’ll also ponder some pachyderms and puzzle over some medical misinformation.

When workers took up the floorboards of a French alpine chateau in the early 2000s, they found penciled messages on their undersides. “Happy mortal,” one read. “When you read this, I shall be no more.” Elsewhere the same hand had written, “My story is short and sincere and frank, because none but you shall see my writing.”

It appears that the carpenter who had installed the floor, Joachim Martin, had written 72 message in pencil to be read by a future generation. “These are the words of an ordinary working man, a man of the people,” Sorbonne historian Jacques-Olivier Boudon told the BBC. “And he is saying things that are very personal, because he knows they will not ever be read except a long time in the future.”

The messages concern events in the rural community of Les Crottes, outside the walls of the Château de Picomtal, whose parquet floor Martin had laid. Among other things, he reveals that he overheard the mistress of one of his friends giving birth in a stable one midnight in 1868. “This [criminal] is now trying to screw up my marriage. All I have to do is say one word and point my finger at the stables, and they’d all be in prison. But I won’t. He’s my old childhood friend. And his mother is my father’s mistress.”

Unfortunately, almost nothing is known about Martin. He lived from 1842 to 1897, he had four children, and he played the fiddle at village fetes. But he found a way to avoid being forgotten.

An encounter between theologian and mathematician Isaac Barrow and John Wilmot, the second Earl of Rochester:

Barrow … met Rochester at court, who said to him, ‘doctor, I am yours to my shoe-tie;’ Barrow bowed obsequiously with, ‘my lord, I am yours to the ground;’ Rochester returned this by, ‘doctor, I am yours to the centre;’ Barrow rejoined, ‘my lord, I am yours to the antipodes;’ Rochester, not to be foiled by ‘a musty old piece of divinity,’ as he was accustomed to call him, exclaimed, ‘doctor, I am yours to the lowest pit of hell;’ whereupon Barrow turned from him with, ‘there, my lord, I leave you.’

From William Hone’s Every-Day Book, 1868.

Inspired officials of the East German Communist party, ever diligent in setting standards to which party members may conform, issued a list of the terms which are approved for use in vilifying the West. Henceforth Red speakers will know they are on safe ground if they choose any of the following synonyms for Americans: ‘Monkey killers, lice breeders, mass poisoners, chewing-gum spivs, boogie-woogie tramps, gas-chamber ideologists, leprous heroes, breeders of trichinosis, arsenic mixers, delirious lunatics, exploiters of epidemics.’ For the British a different set of terms must be used: ‘paralytic sycophants, effete betrayers of humanity, carrion-eating servile imitators, arch cowards and collaborators, conceited dandies or playboy soldiers.’

— LIFE, Sept. 14, 1953

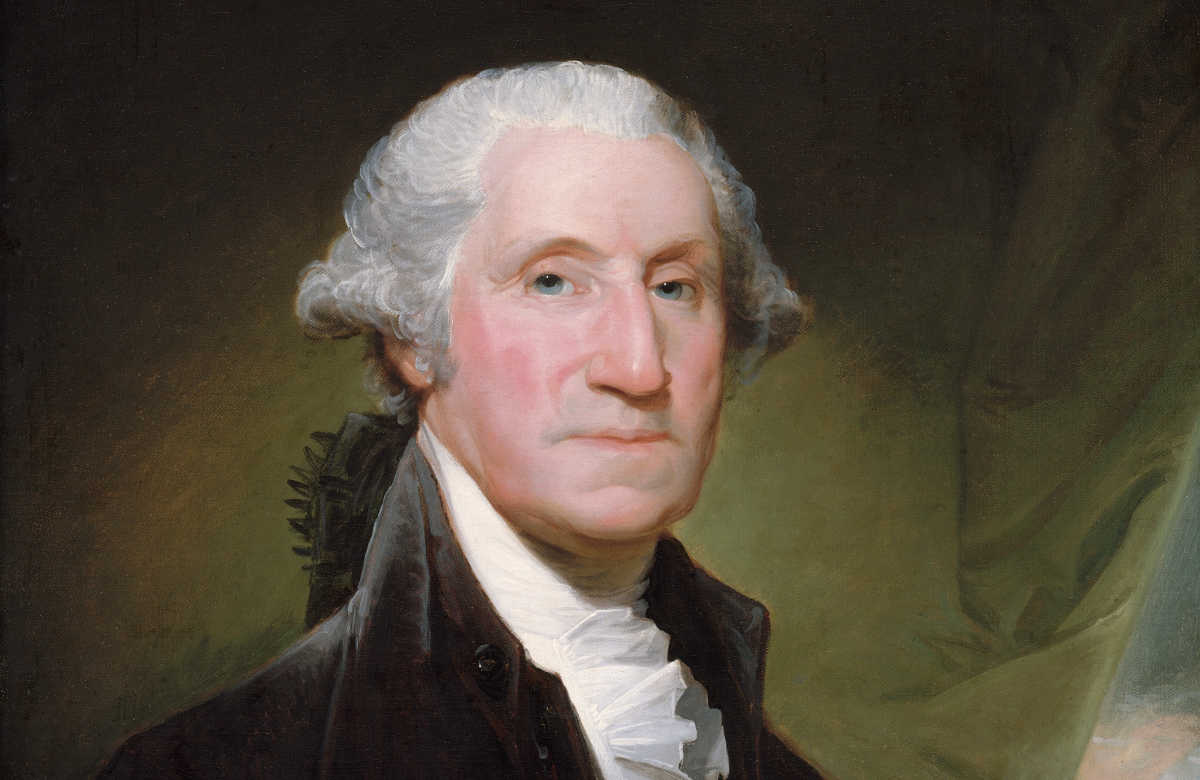

When George Washington died in 1799, the British Royal Navy’s Channel Fleet lowered its flags to half mast.

The London Courier wrote, “The whole range of history does not present to our view a character upon which we can dwell with such entire and unmixed admiration.”