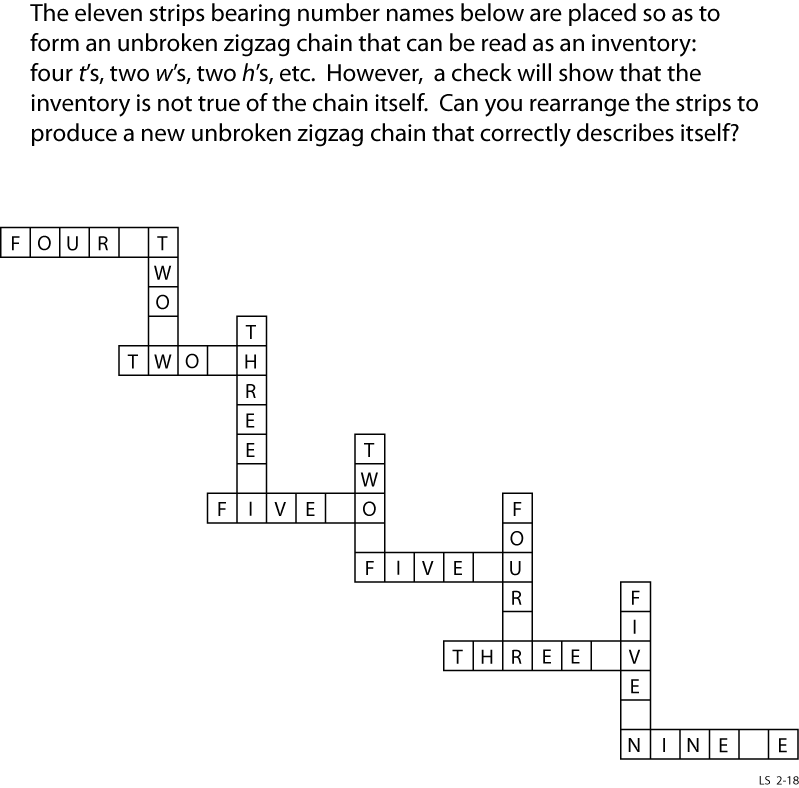

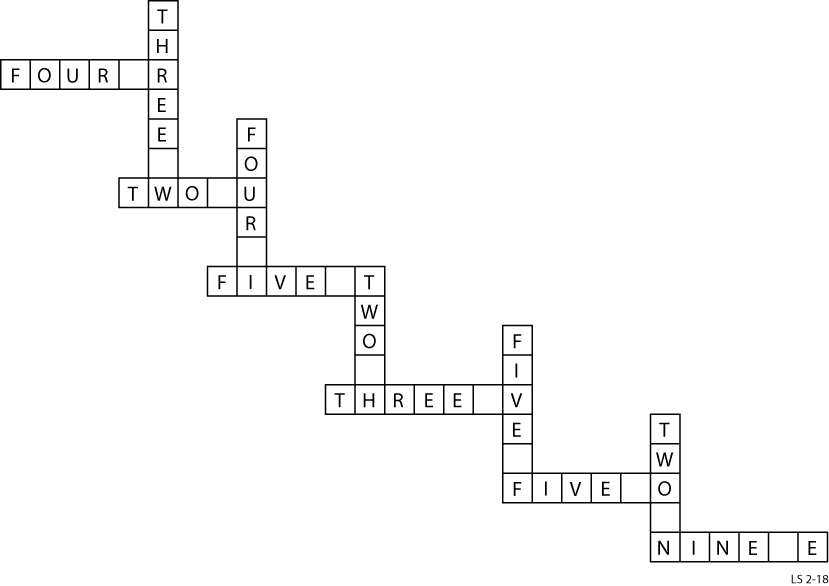

Zigzag

Free Thinking

Arthur Conan Doyle in Tit-Bits, Dec. 15, 1900:

There is one fact in connection with Holmes which will probably interest those who have followed his career from the beginning, and to which, so far as I am aware, attention has never been drawn. In dealing with criminal subjects one’s natural endeavour is to keep the crime in the background. In nearly half the number of the Sherlock Holmes stories, however, in a strictly legal sense no crime was actually committed at all. One heard a good deal about crime and the criminal, but the reader was completely bluffed. Of course, I could not bluff him always, so sometimes I had to give him a crime, and occasionally I had to make it a downright bad one.

A footnote from Leslie Klinger’s New Annotated Sherlock Holmes, 2005:

Fletcher Pratt computes that by 1914, when the record of Holmes’s detective activities ceases, no crimes had taken place in one quarter of the total published cases. In nine of these cases, there was no legal crime. In six no crime took place because Holmes intervened in time to prevent its occurrence.

The Blythe Intaglios

In 1932, pilot George Palmer was flying from Las Vegas to Blythe, Calif., when he saw drawings sketched on the desert. Someone had scraped away the dark surface soil to draw three human figures, two four-legged animals, and a spiral.

Because they’re so large (the largest human figure is 171 feet long), they’d gone unnoticed until then. No local Native American group claims to have made them; radiocarbon dating places their creation between 900 BCE and 1200 CE.

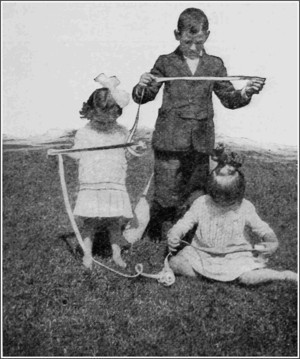

“The Longest Letter in the World”

Your friends are always asking for long letters. To supply this demand a man in Los Angeles, California, has invented a little novelty that has captured the fancy of visiting tourists.

It consists of a roll of paper tape sixty feet long. The paper is made to write on, and has a place for the name and address of the sender and receiver. It goes as first class mail for two cents, like any other letter, and can be mailed in any mail box.

These little ‘long letters’ cause many a laugh and one can write a regular letter on the tape, by merely unrolling it as it is used up.

— Popular Science Monthly, February 1916

Podcast Episode 202: The Rosenhan Experiment

In the 1970s psychologist David Rosenhan sent healthy volunteers to 12 psychiatric hospitals, where they claimed to be hearing voices. Once they were admitted, they behaved normally, but the hospitals diagnosed all of them as seriously mentally ill. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll describe the Rosenhan experiment, which challenged the validity of psychiatric diagnosis and set off a furor in the field.

We’ll also spot hawks at Wimbledon and puzzle over a finicky payment processor.

Right and Wrong

In a series of experiments in 2009, Stanford psychologist Daniel Casasanto investigated whether right- and left-handed people differ in how they associate abstract concepts such as good and bad with horizontal space.

He found that right-handed people associate the space to their right with good things like intelligence, attractiveness, honesty, and happiness more readily than the space to their left. With left-handed people, the opposite applies.

“This means for example that the same portrait photo, when placed on a table to the right of a right-hander, will be seen in a more positive light than when it happens to be placed on the other side,” writes Rik Smits in The Puzzle of Left-Handedness. “It’s as if the preference for one hand over the other radiates out into the vicinity of that hand. It may even mean that when an employer looks at a list of brief descriptions of job applications that has been laid out in two columns, those in the column of the same same side as his or her preferred hand will be judged more favourably. If this turns out to be true, then perhaps elections, selection procedures and recruitment are even less rational processes than we already feared. It seems there isn’t an awful lot we can do about that.”

(Daniel Casasanto, “Embodiment of Abstract Concepts: Good and Bad in Right- and Left-Handers,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 138:3 [August 2009], 351–367.)

Low Tech

Woodworking engineer Matthias Wandel built a 6-bit wooden adding machine driven by marbles.

More info (and more gizmos) at his website.

Hmm

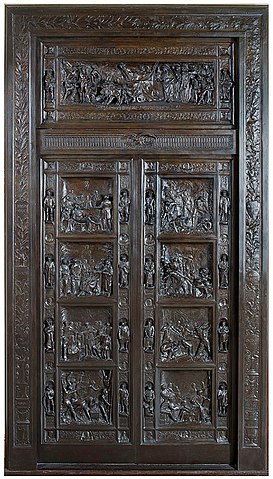

Maybe this is symbolic — the U.S. Capitol contains a pair of “doors to nowhere” that serve no purpose.

In 1901 sculptor Louis Amateis designed a set of bronze doors to grace the reconstructed façade of the building’s West Front. But when the doors were cast in 1910, legislation for the improvement still had not been authorized, so they couldn’t be installed.

The “Amateis Doors” were displayed in various museums until 1967 and then placed in storage. They were finally hung in the Capitol in 1972, just downstairs from the Rotunda … where they seem to promise great things but ultimately lead nowhere.

The Inner World

In 1948 the Italian composer Giacinto Scelsi entered a sanatorium in the Swiss Alps, where he began to pass the time by repeatedly striking a single piano key and listening intently to its sound. He said later:

Reiterating a note for a long time, it grows large, so large that you even hear harmony growing inside it. … When you enter into a sound, the sound envelops you and you become part of the sound. Gradually, you are consumed by it and you need no other sound. … All possible sounds are contained in it.

The result, eventually, was his 1959 composition Quattro pezzi (ciascuno su una nota sola) (“Four Pieces, Each on a Single Note”) for chamber orchestra, in which each movement concentrates on a single pitch, with varying timbre and dynamics.

He wrote, “I will say only that in general, western classical music has devoted practically all of its attention to the musical framework, which it calls the musical form. It has neglected to study the laws of sonorous energy, to think of music in terms of energy, which is life. … The inner space is empty.”

While we’re at it: Here’s how Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up” would sound if all the notes were C:

(Gregory N. Reish, “Una Nota Sola: Giacinto Scelsi and the Genesis of Music on a Single Note,” Journal of Musicological Research 25 [2006] 149–189.)