Here are five new lateral thinking puzzles — play along with us as we try to untangle some perplexing situations using yes-or-no questions.

Here are five new lateral thinking puzzles — play along with us as we try to untangle some perplexing situations using yes-or-no questions.

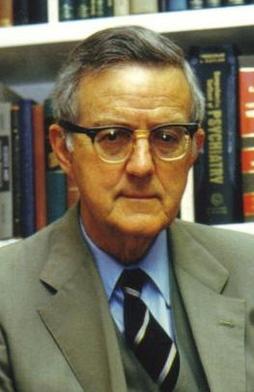

In 1967, Ian Stevenson closed a combination lock and placed it in a filing cabinet in the psychiatry department at the University of Virginia. He had set the combination using a word or phrase known only to himself. He told his colleagues that he would try to communicate the code to them after his death, as potential evidence that his awareness had survived.

The combination “is extremely meaningful to me,” he said. “I have no fear whatever of forgetting it on this side of the grave and, if I remember anything on the other side, I shall surely remember it.”

His colleague Emily Williams Kelly told the New York Times, “Presumably, if someone had a vivid dream about him, in which there seemed to be a word or a phrase that kept being repeated — I don’t quite know how it would work — if it seemed promising enough, we would try to open it using the combination suggested.”

Stevenson died in 2007. As of October 2014, the lock remained unopened.

In 2004, using the memorable experiment above, psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris showed that when viewers are concentrating on a task they can become functionally blind to unexpected objects and events.

Remarkably, Cambridge-based parapsychologist A.D. Cornell had earlier demonstrated a similar effect in an even stranger experiment. In 1959 he dressed up in a white sheet and “haunted” a cow pasture near King’s College; none of approximately 80 passers-by seemed to notice anything at all. When he moved the “ghost walk” to the graveyard of St Peter’s Church, 4 of 142 people gave any clear indication of having seen the “experimental apparition,” and none of them thought they’d seen anything paranormal. (One saw “a man dressed as a woman, who surely must be mad,” one saw “an art student walking about in a blanket,” and two said “we could see his legs and feet and knew it was a man dressed in some white garment.”)

The following year Cornell again dressed as a ghost and passed twice across the screen in an X-rated cinema. 46% of the respondents failed to notice his first passage, and 32% remained completely unaware of him. One person thought she’d seen a polar bear, and another reported a fault in the projector. Only one correctly described a man dressed in a sheet pretending to be a ghost. Cornell concluded that the number of “true” hauntings may be grossly under-reported.

(A.D. Cornell, “An Experiment in Apparitional Observation and Findings,” Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 40:701, 120-124; A.D. Cornell, “Further Experiments in Apparitional Observation,” Journal of the Society for Psychical Research 40:706, 409-418.) (Thanks, Elizabeth.)

“Is the old maxim true about there being an exception to every rule? Well, no doubt we can all think of rules that appear to have no exceptions, but since appearances can be deceiving, maybe the old maxim is true. On the other hand, the maxim is itself a rule, so if we assume that it’s true, it has an exception, which would be tantamount to saying that there is some rule that has no exception. So if the maxim is true, it’s false. That makes it false. Thus we know at least one rule that definitely has an exception, viz., ‘There’s an exception to every rule,’ and, although we haven’t identified it, we know that there is at least one rule that has no exceptions.”

— David L. Silverman, Word Ways, February 1972

Raymond Smullyan used to send emails to friends that read, “Please ignore this message.”

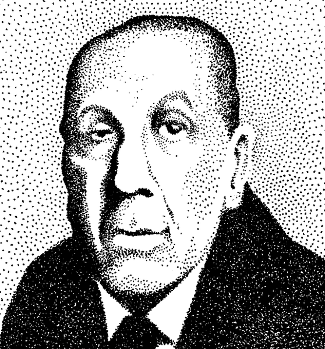

“I don’t like writers who are making sweeping statements all the time. Of course, you might argue that what I’m saying is a sweeping statement, no?” — Jorge Luis Borges, quoted in Floyd Merrell, Unthinking Thinking, 1991

Stare at the cross from a short distance away without moving your eyes. After a few seconds, the colors will fade away.

The effect was discovered by Swiss physician Ignaz Paul Vital Troxler in 1804. The reasons for it aren’t clear — possibly neurons in the visual system adapt to unchanging stimuli and they drop out of our awareness.

Mistaken reports received by the SPCA on the British island of Guernsey:

In June 2016 a member of the public brought in a “dead cat” that turned out to be a dog puppet (“a very muddy, wet, insect covered, cold, collapsed small dog with an injured nose”).

“Both the finder and I were extremely relieved and where an air of sadness had been at the GSPCA it soon turned to laughter,” said SPCA manager Steve Byrne.

They advertised for the owner on Facebook, but I don’t know that anyone ever responded.

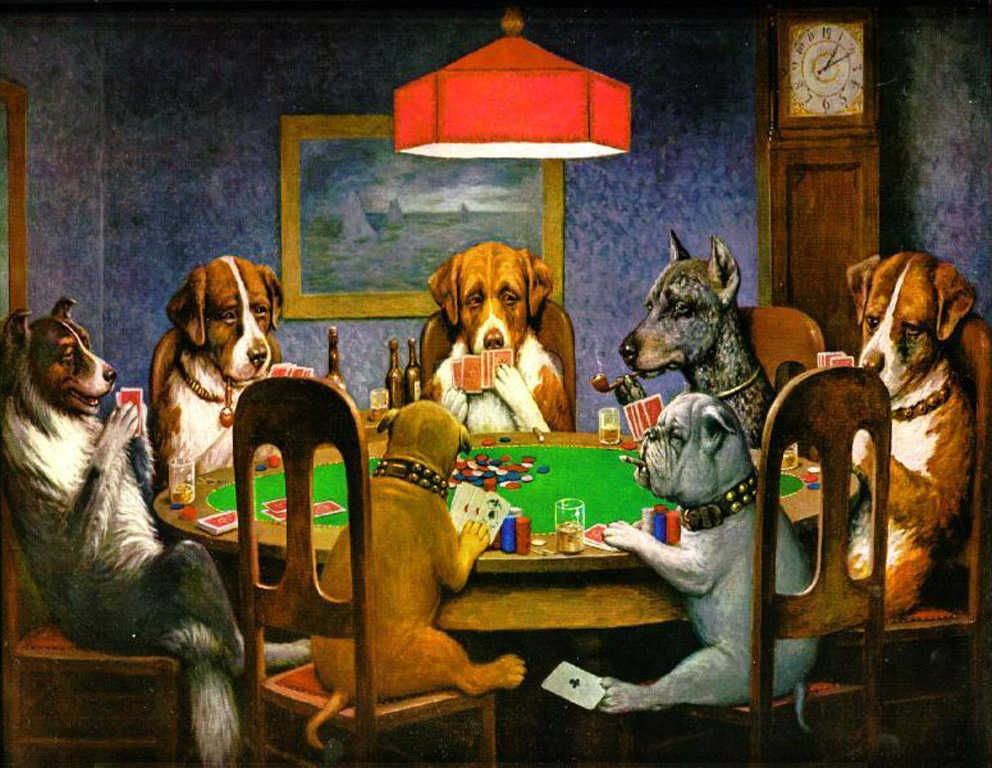

In poker, suppose you’re dealt a pair. Is the probability that your opponent also holds a pair higher, lower, or the same as it would be if you held nothing?

For his 2004 book Tell Me Another!, Jack Aspinwall asked members of Parliament to tell him jokes and stories. Richard Ottaway told him this:

The Duchess returned to the Manor one evening and encountered her butler in her boudoir. She looked the butler straight in the eye and said:

“James, take off my dress.” James took off her dress.

“James, take off my petticoat.” James took off her petticoat.

“James, take off my bra.” James took off her bra.

“James, take off my panties.” James took off her panties. The Duchess turned, faced her butler again and in a soft but firm voice said:

“Now then, James, never let me catch you wearing my clothes again.”

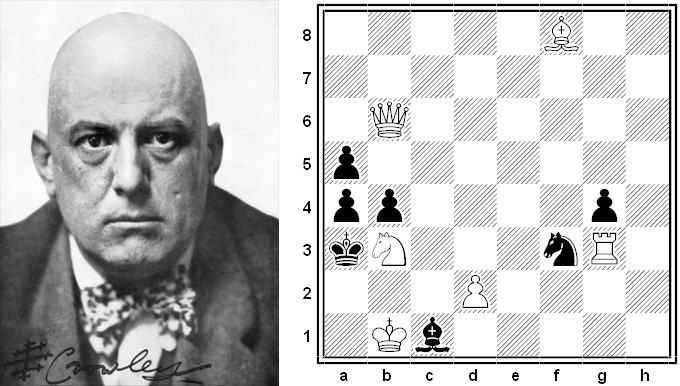

The English occultist Aleister Crowley, “the wickedest man in the world,” was a skilled chess player. In 1894 he published several problems in the Eastbourne Gazette under the pseudonym Ta Dhuibh. This one appeared on Feb. 21. How can White mate in two moves?

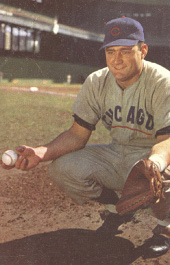

Catcher Harry Chiti pulled a sort of ontological sleight in 1962.

On April 25, while playing for the Cleveland Indians, he was acquired by the expansion New York Mets for a player to be named later.

Seven weeks later, on June 15, he was sent back to the Indians as the “player to be named later” — he’d been traded for himself.

Three other players have since achieved the same feat: Dickie Noles, Brad Gulden, and John McDonald.

(Thanks, Tom.)