In a diary entry in 1843, Sir Oswald Brierly, manager of the whaling station at Twofold Bay in southeast Australia, noted a strange cooperative relationship that had grown up between killer whales and the local whalers:

They [the killer whales] attack the [humpback] whales in packs and seem to enter keenly into the sport, plunging about the [whaling] boat and generally preventing the whale from escaping by confusing and meeting him at every turn. … The whalemen of Twofold Bay are very favourably disposed towards the killers and regard it as a good sign when they see a whale ‘hove to’ by these animals because they regard it as an easy prey when assisted by their allies the killers.

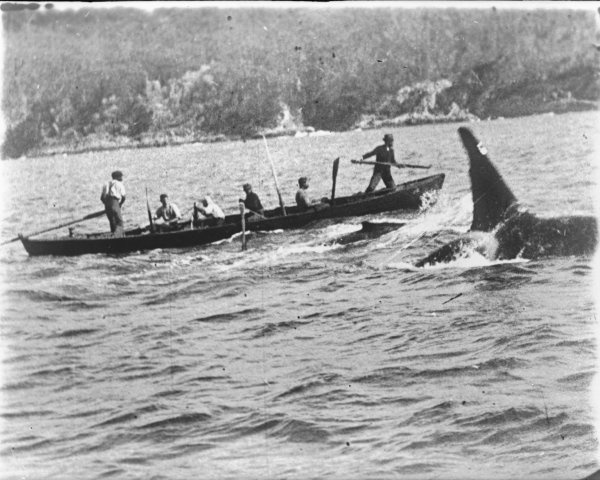

By the early 20th century this curious custom had grown into a complex operation. The killer whales would herd a passing humpback into the bay and harass it there while others swam to the whaling station, breached, and thrashed their tails to alert the whalers. When the whalers arrived and harpooned the humpback, the killers would continue to leap onto its back and blowhole to tire it. In return, the whalers would anchor the dead whale to the bottom for a day or two so that the killers could feast on its lips and tongue.

The whalers came to know many of these killer whales by name: Hooky, Cooper, Typee, Jackson, and so on. The most famous, Old Tom, worked with the Twofold Bay whalers for almost four decades in the early 20th century — he grew famous for gripping the harpoon line with his teeth as each doomed humpback towed the whaleboat through the water. He died in 1930, and his skeleton, complete with grooves in the teeth, now resides in the Eden Killer Whale Museum in New South Wales.

(From Hal Whitehead and Luke Rendell, The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins, 2014. See A Feathered Maître d’.)