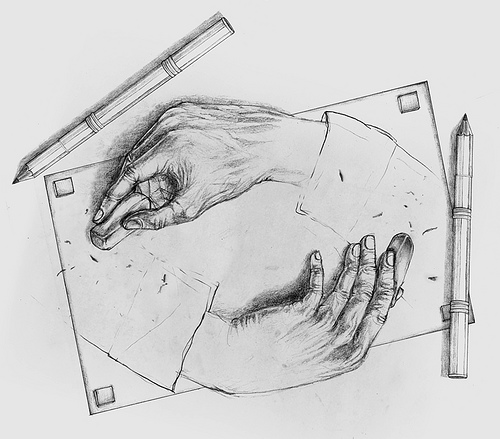

“Erasing Hands,” by Malaysian illustrator Tang Yau Hoong. What happens next?

“Erasing Hands,” by Malaysian illustrator Tang Yau Hoong. What happens next?

In 1914, the rim of the New Zealand volcano Whakaari collapsed, burying a sulfur mining operation and killing 10 men.

“Remarkably, there was one survivor: the camp cat, Peter the Great,” notes Sarah Lowe in New Zealand Geographic. “The cat returned to Whakatane, perhaps with one life less, but with unimpaired virility: many Whakatane cat owners trace their pet’s genealogy back to this hardy beast.”

It’s sometimes said that a cat named Tibbles dispatched the last living Lyall’s wren from Stephens Island, also in New Zealand, making her the only known individual to have extirpated an entire species. It’s more likely that a colony of feral cats overran the island, the birds’ last refuge. But maybe one of them was named Tibbles!

In his notebook, Mark Twain wrote, “A cat is more intelligent than people believe, and can be taught any crime.”

In 2013, artist Kim Beaton and 25 volunteers constructed a 12-foot papier-mâché “tree troll” with the kindly face of the sculptor’s late father, Hezzie Strombo, a Montana lumberjack.

[My father] had died a few months prior at 80 years old. On June 2nd, at 3am, I woke from a dream with a clear vision burning in my mind. The image of my dad, old, withered and ancient, transformed into one of the great trees, sitting quietly in a forest. I leaped from my bed, grabbed some clay and sculpted like my mind was on fire. In 40 minutes I had a rough sculpture that said what it needed to. The next morning I began making phone calls, telling my friends that in 6 days time we would begin on a new large piece. The next 6 days, I got materials and made more calls. On June 8th we began, and 15 days later we were done. I have never in my life been so driven to finish a piece.

The troll now makes holiday appearances at the Bellagio casino in Las Vegas.

(From My Modern Met.)

When American forces overran the Philippine island of Lubang in 1945, Japanese intelligence officer Hiroo Onoda withdrew into the mountains to wait for reinforcements. He was still waiting 29 years later. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll meet the dedicated soldier who fought World War II until 1974.

We’ll also dig up a murderer and puzzle over an offensive compliment.

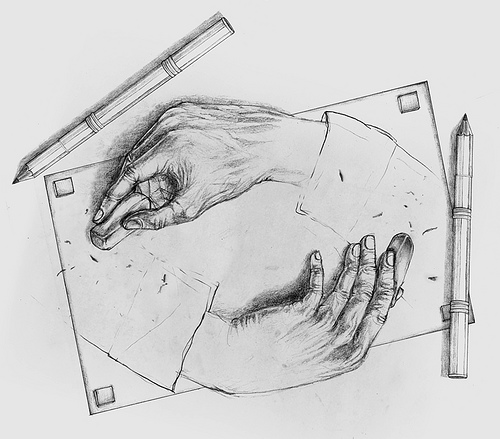

Ukrainian artist Oleg Shuplyak specializes in “Hidden Images,” in which famous faces emerge from simple scenes.

Initially trained as an architect, he’s been a member since 2000 of the National Union of Artists of Ukraine.

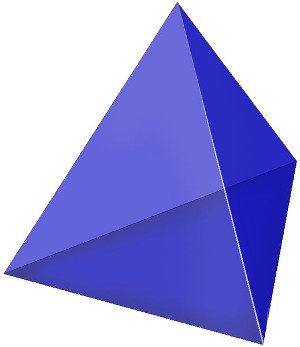

In the humble tetrahedron, each face shares an edge with each other face. Surprisingly, there’s only one other known polyhedron in which this is true — the Szilassi polyhedron, discovered in 1977 by Hungarian mathematician Lajos Szilassi:

If there’s a third such creature it would have 44 vertices and 66 edges, and no one knows whether such a shape could even be contrived. It remains an unsolved problem.

oppidan

adj. of a university town

The Mercantile Library of Cincinnati has a 10,000-year lease. When Cincinnati College burned in 1845, the young men of the city’s Mercantile Library Association helped to rebuild it. As a reward, the library was given a lease of ten millennia on the 11th and 12th floors of the Mercantile Library Building in downtown Cincinnati.

The current lease will expire in the year 11845 — but it’s renewable.

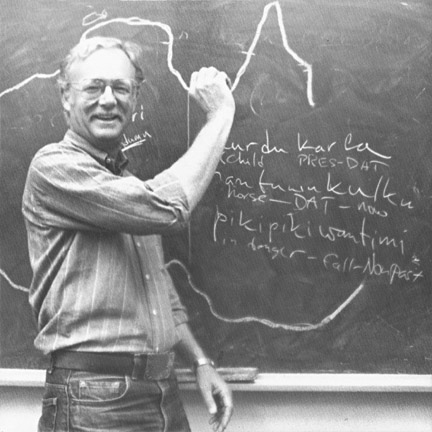

Linguist Ken Hale had a preternatural ability to learn new languages. “It was as if the linguistic faculty which normally shuts off in human beings at the age of 12 just never shut off in him,” said his MIT colleague Samuel Jay Keyser.

“It’s more like a musical talent than anything else,” Hale told The New York Times in 1997. “When I found out I could speak Navajo at the age of 12, I used to go out every day and sit on a rock and talk Navajo to myself.” Acquiring new languages became a lifelong obsession:

In Spain he learnt Basque; in Ireland he spoke Gaelic so convincingly that an immigration officer asked if he knew English. He apologised to the Dutch for taking a whole week to master their somewhat complex language. He picked up the rudiments of Japanese after watching a Japanese film with subtitles.

He estimated that he could learn the essentials of a new language in 10 or 15 minutes, well enough to make himself understood, if he could talk to a native speaker (he said he could never learn a language in a classroom). He would start with parts of the body, he said, then animals and common objects. Once he’d learned the nouns he could start to make sentences and master sounds, writing everything down.

He devoted much of his time to studying vanishing languages around the world. He labored to revitalize the language of the Wampanoag in New England and visited Nicaragua to train linguists in four indigenous languages. In 2001 his son Ezra delivered his eulogy in Warlpiri, an Australian aboriginal language that his father had raised his sons to speak. “The problem,” Ken once told Philip Khoury, “is that many of the languages I’ve learned are extinct, or close to extinction, and I have no one to speak them with.”

“Ken viewed languages as if they were works of art,” recalled another MIT colleague, Samuel Jay Keyser. “Every person who spoke a language was a curator of a masterpiece.”