Allan William Johnson discovered this “magic square of squares” in 1990:

302 2462 1722 452 932 1162 662 2582 1262 1382 2372 442 2602 32 542 1502

Each row, column, and long diagonal totals 93025, or 3052.

Allan William Johnson discovered this “magic square of squares” in 1990:

302 2462 1722 452 932 1162 662 2582 1262 1382 2372 442 2602 32 542 1502

Each row, column, and long diagonal totals 93025, or 3052.

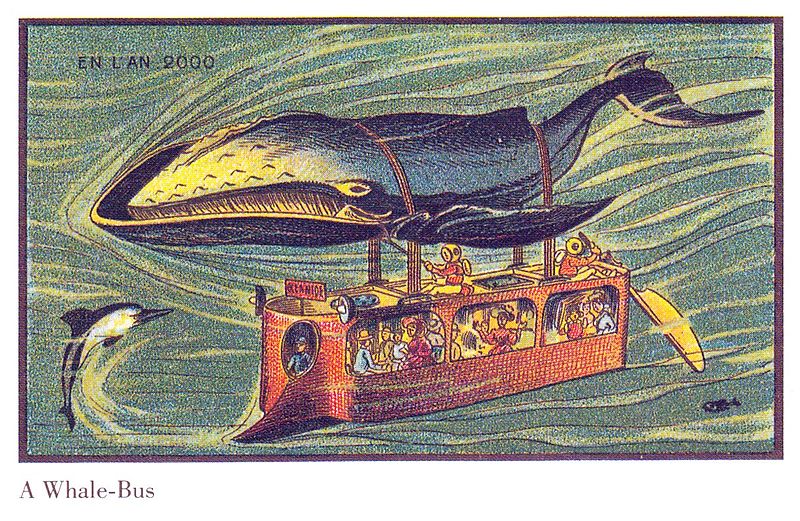

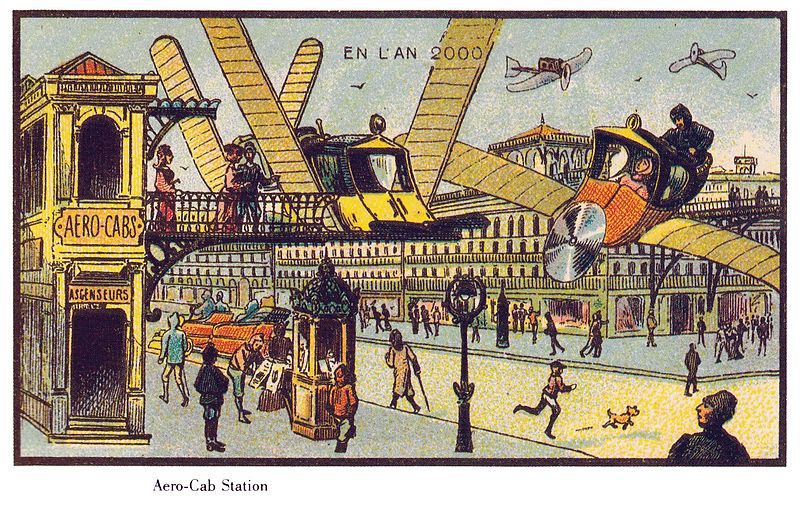

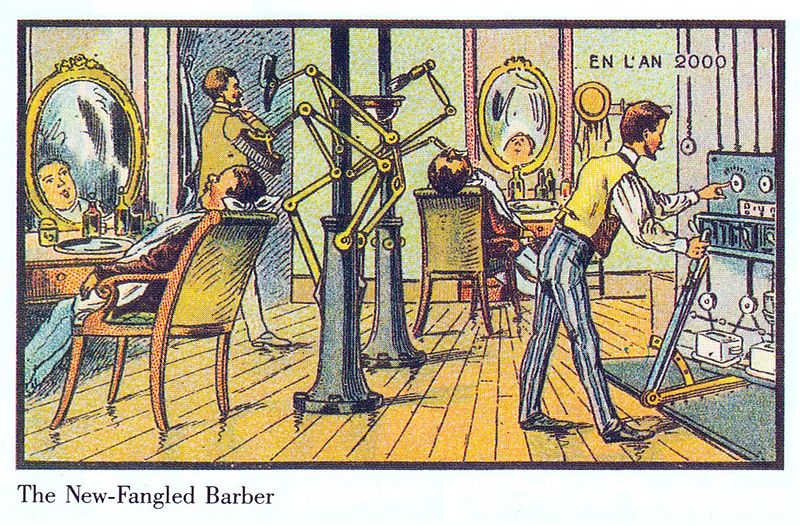

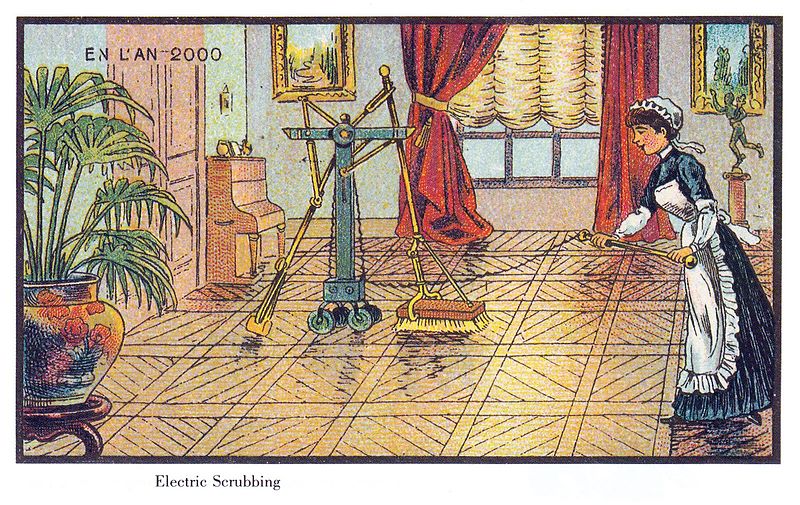

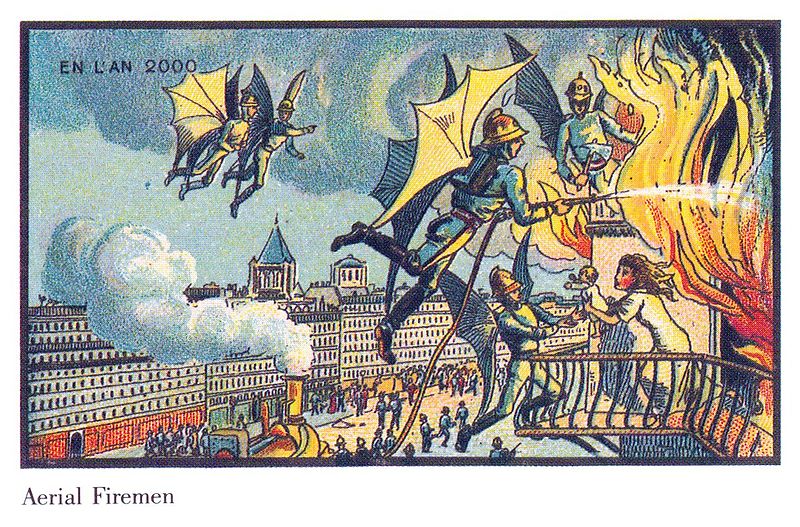

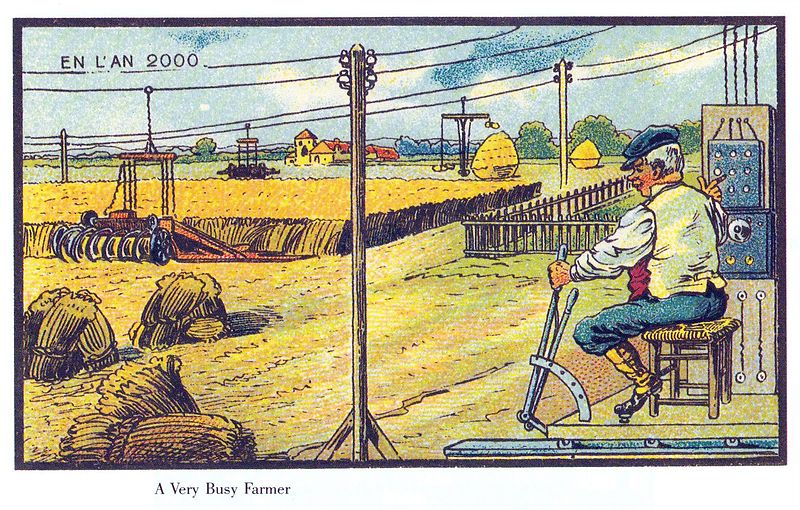

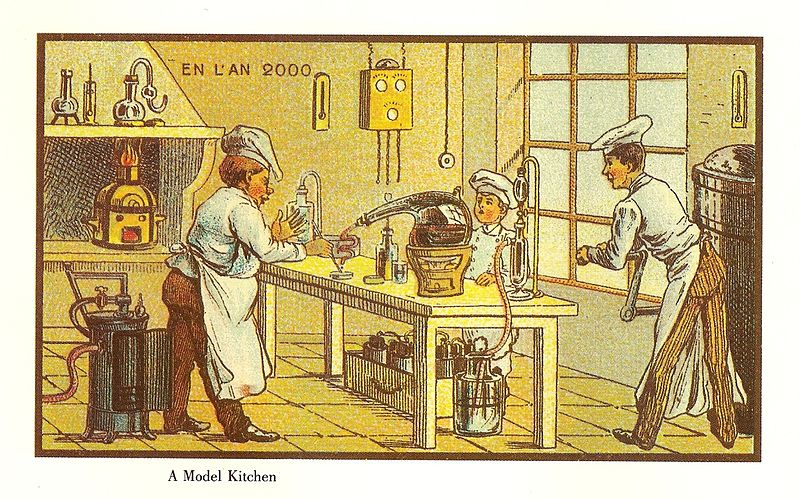

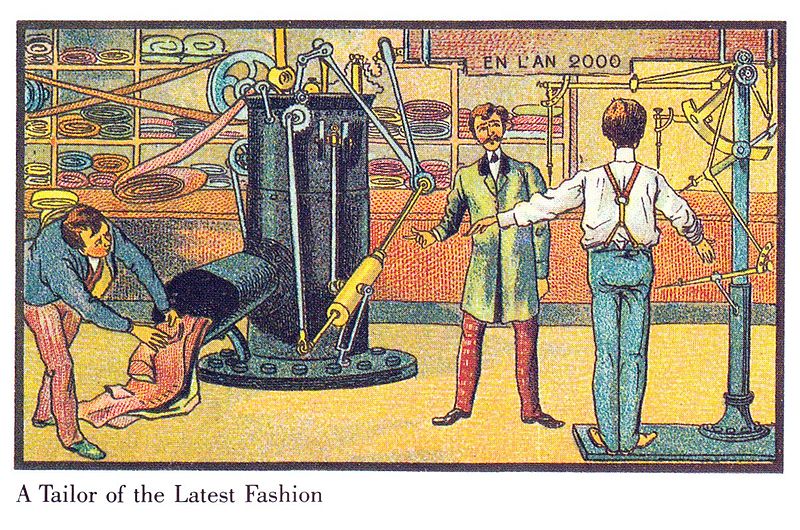

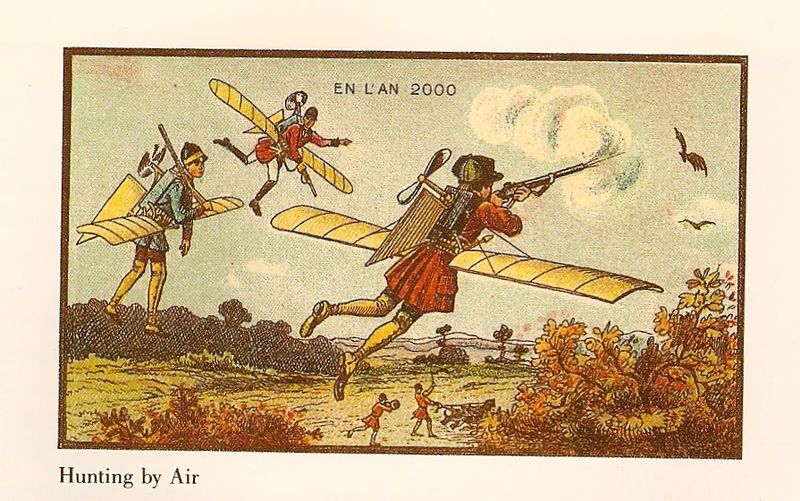

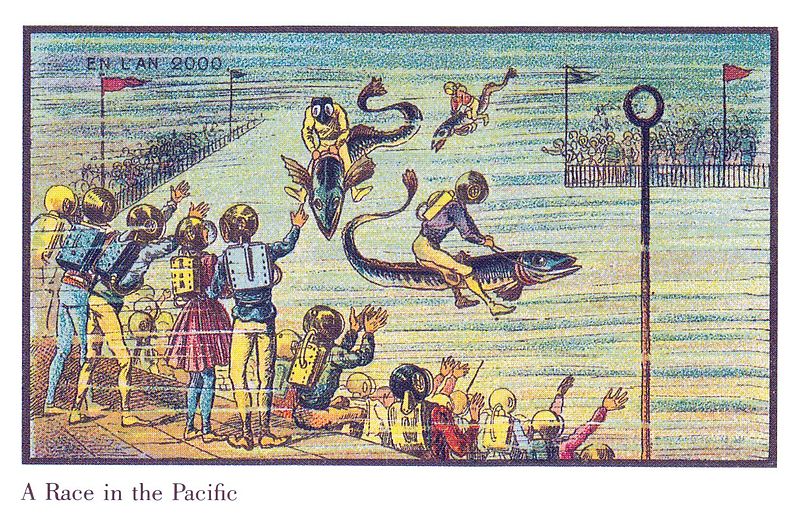

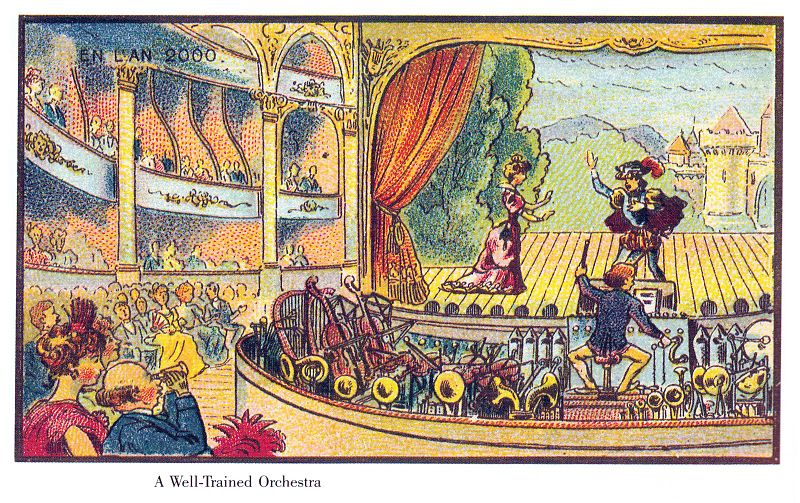

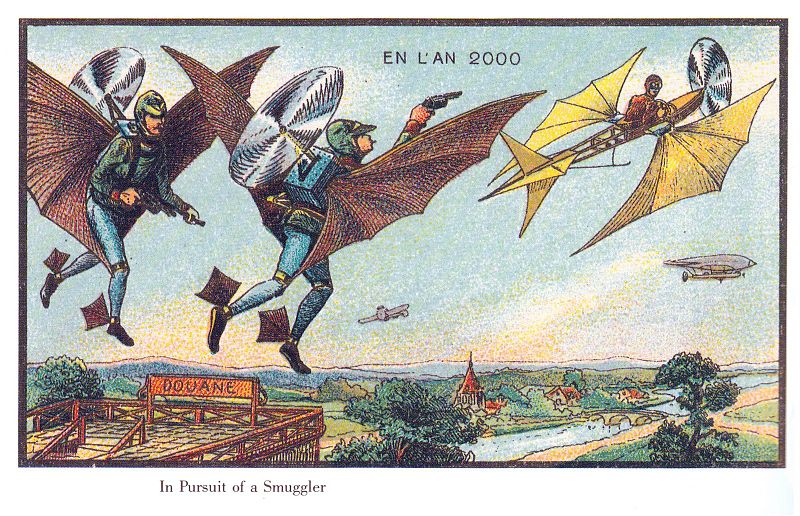

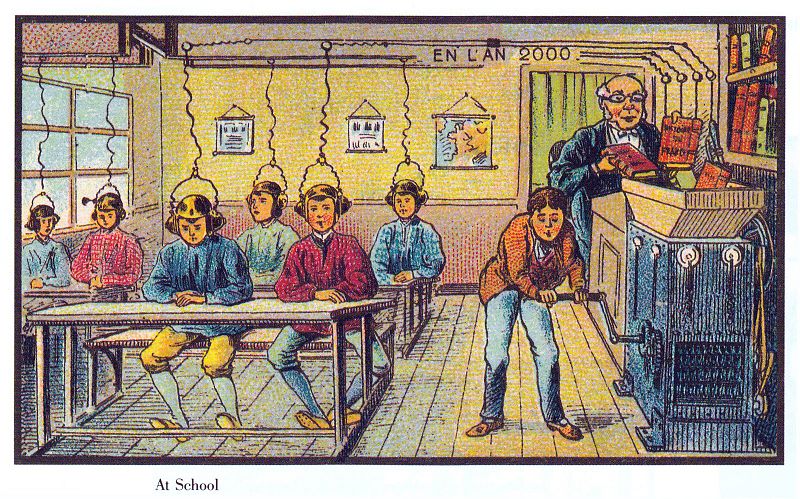

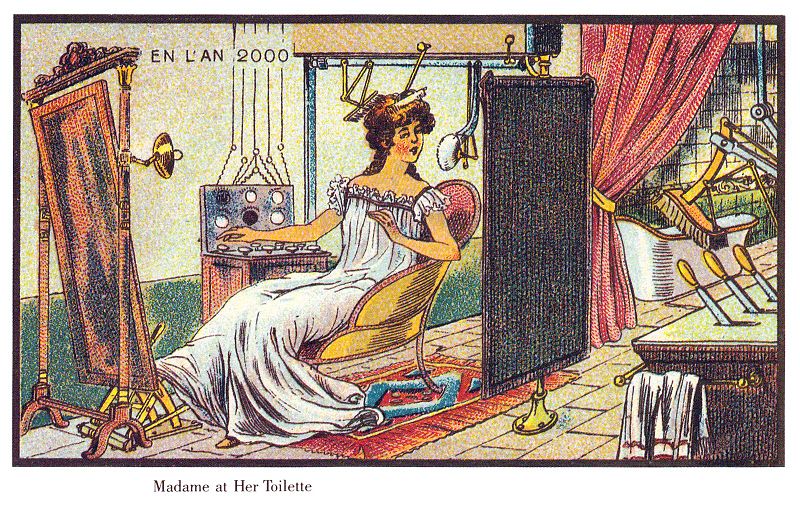

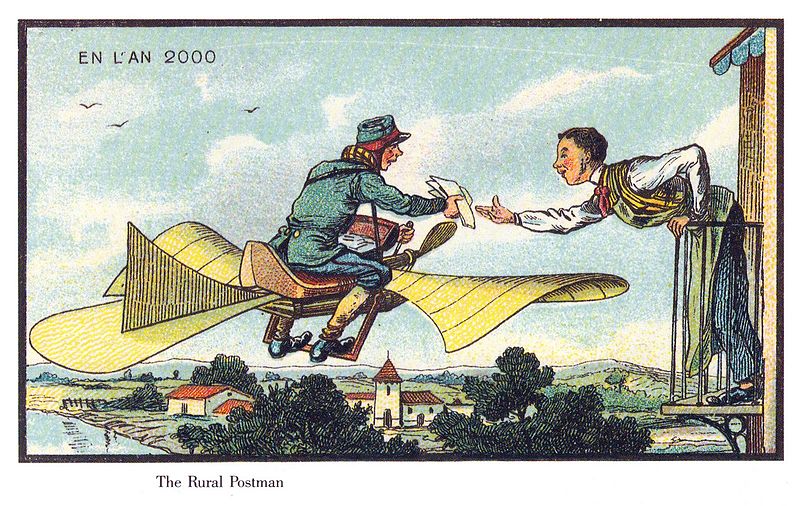

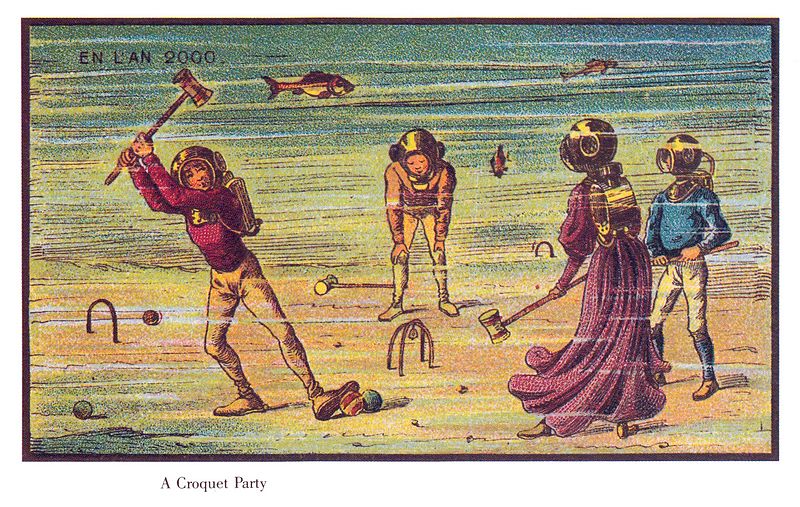

In 1899, preparing for festivities in Lyon marking the new century, French toy manufacturer Armand Gervais commissioned a set of 50 color engravings from freelance artist Jean-Marc Côté depicting the world as it might exist in the year 2000.

The set itself has a precarious history. Gervais died suddenly in 1899, when only a few sets had been run off the press in his basement. “The factory was shuttered, and the contents of that basement remained hidden for the next twenty-five years,” writes James Gleick in Time Travel. “A Parisian antiques dealer stumbled upon the Gervais inventory in the twenties and bought the lot, including a single proof set of Côté’s cards in pristine condition. He had them for fifty years, finally selling them in 1978 to Christopher Hyde, a Canadian writer who came across his shop on rue de l’Ancienne-Comédie.”

Hyde showed them to Isaac Asimov, who published them in 1986 as Futuredays, with a gentle commentary on what Côté had got right (widespread automation) and wrong (clothing styles). But maybe some of these visions are still ahead of us:

“The cocky characters, for some reason, the public seems to like. They don’t like those kinds of people in real life.” — Friz Freleng

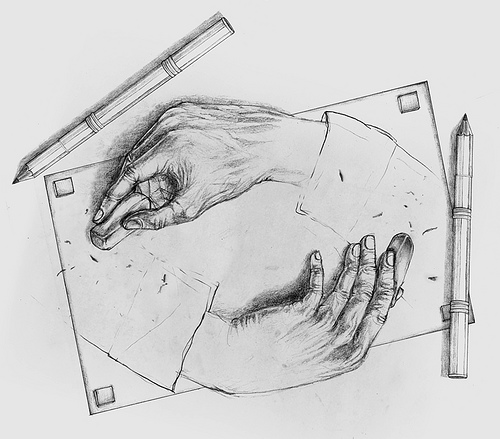

“Erasing Hands,” by Malaysian illustrator Tang Yau Hoong. What happens next?

In 1914, the rim of the New Zealand volcano Whakaari collapsed, burying a sulfur mining operation and killing 10 men.

“Remarkably, there was one survivor: the camp cat, Peter the Great,” notes Sarah Lowe in New Zealand Geographic. “The cat returned to Whakatane, perhaps with one life less, but with unimpaired virility: many Whakatane cat owners trace their pet’s genealogy back to this hardy beast.”

It’s sometimes said that a cat named Tibbles dispatched the last living Lyall’s wren from Stephens Island, also in New Zealand, making her the only known individual to have extirpated an entire species. It’s more likely that a colony of feral cats overran the island, the birds’ last refuge. But maybe one of them was named Tibbles!

In his notebook, Mark Twain wrote, “A cat is more intelligent than people believe, and can be taught any crime.”

In 2013, artist Kim Beaton and 25 volunteers constructed a 12-foot papier-mâché “tree troll” with the kindly face of the sculptor’s late father, Hezzie Strombo, a Montana lumberjack.

[My father] had died a few months prior at 80 years old. On June 2nd, at 3am, I woke from a dream with a clear vision burning in my mind. The image of my dad, old, withered and ancient, transformed into one of the great trees, sitting quietly in a forest. I leaped from my bed, grabbed some clay and sculpted like my mind was on fire. In 40 minutes I had a rough sculpture that said what it needed to. The next morning I began making phone calls, telling my friends that in 6 days time we would begin on a new large piece. The next 6 days, I got materials and made more calls. On June 8th we began, and 15 days later we were done. I have never in my life been so driven to finish a piece.

The troll now makes holiday appearances at the Bellagio casino in Las Vegas.

(From My Modern Met.)

When American forces overran the Philippine island of Lubang in 1945, Japanese intelligence officer Hiroo Onoda withdrew into the mountains to wait for reinforcements. He was still waiting 29 years later. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll meet the dedicated soldier who fought World War II until 1974.

We’ll also dig up a murderer and puzzle over an offensive compliment.

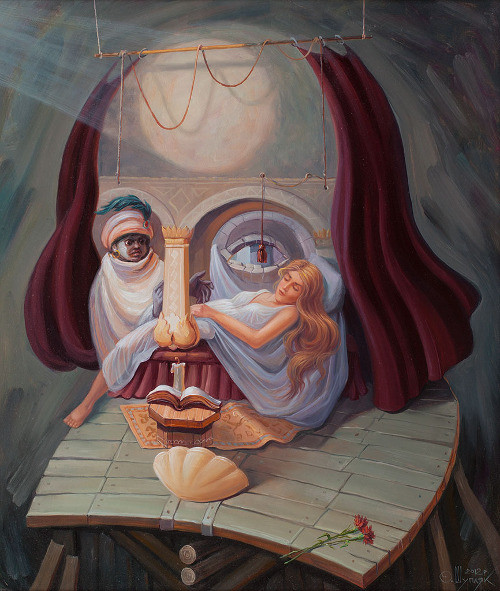

Ukrainian artist Oleg Shuplyak specializes in “Hidden Images,” in which famous faces emerge from simple scenes.

Initially trained as an architect, he’s been a member since 2000 of the National Union of Artists of Ukraine.

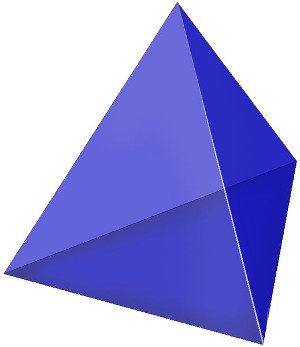

In the humble tetrahedron, each face shares an edge with each other face. Surprisingly, there’s only one other known polyhedron in which this is true — the Szilassi polyhedron, discovered in 1977 by Hungarian mathematician Lajos Szilassi:

If there’s a third such creature it would have 44 vertices and 66 edges, and no one knows whether such a shape could even be contrived. It remains an unsolved problem.