One more Sherlock Holmes oddity: “The Adventure of the Cardboard Box” appeared in the Strand in 1893. In it, Holmes tells Watson, “As a medical man, you are aware, Watson, that there is no part of the body which varies so much as the human ear. Each ear is as a rule quite distinctive and differs from all other ones. In last year’s Anthropological Journal you will find two short monographs from my pen upon the subject.”

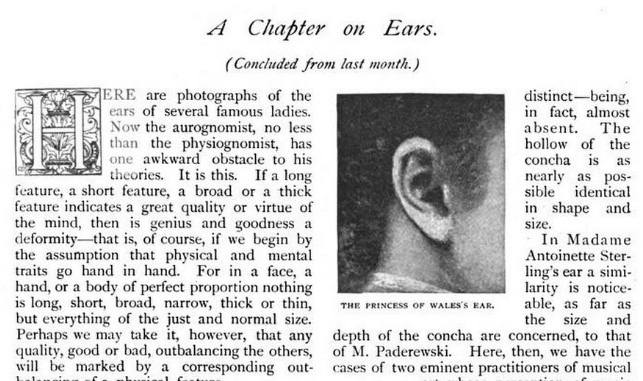

Just a few months later, in October and November 1893, the Strand published “A Chapter on Ears,” analyzing the ears of famous Britons. Interestingly, the article carries no byline. Was it inspired by the story, or is it the work of Sherlock Holmes himself?

Christopher Morley noted that one of the featured ears was that of Oliver Wendell Holmes. “Surely, from so retiring a philosopher, then eighty-four years old, this intimate permission could not have been had without the privileged intervention of Sherlock.”