Amazingly, each of these denominators is the product of two distinct primes (discovered by A.W. Johnson in 1978).

Can a sum of such fractions produce any natural number? That’s conjectured — but so far unproven.

(Thanks, Sid.)

Amazingly, each of these denominators is the product of two distinct primes (discovered by A.W. Johnson in 1978).

Can a sum of such fractions produce any natural number? That’s conjectured — but so far unproven.

(Thanks, Sid.)

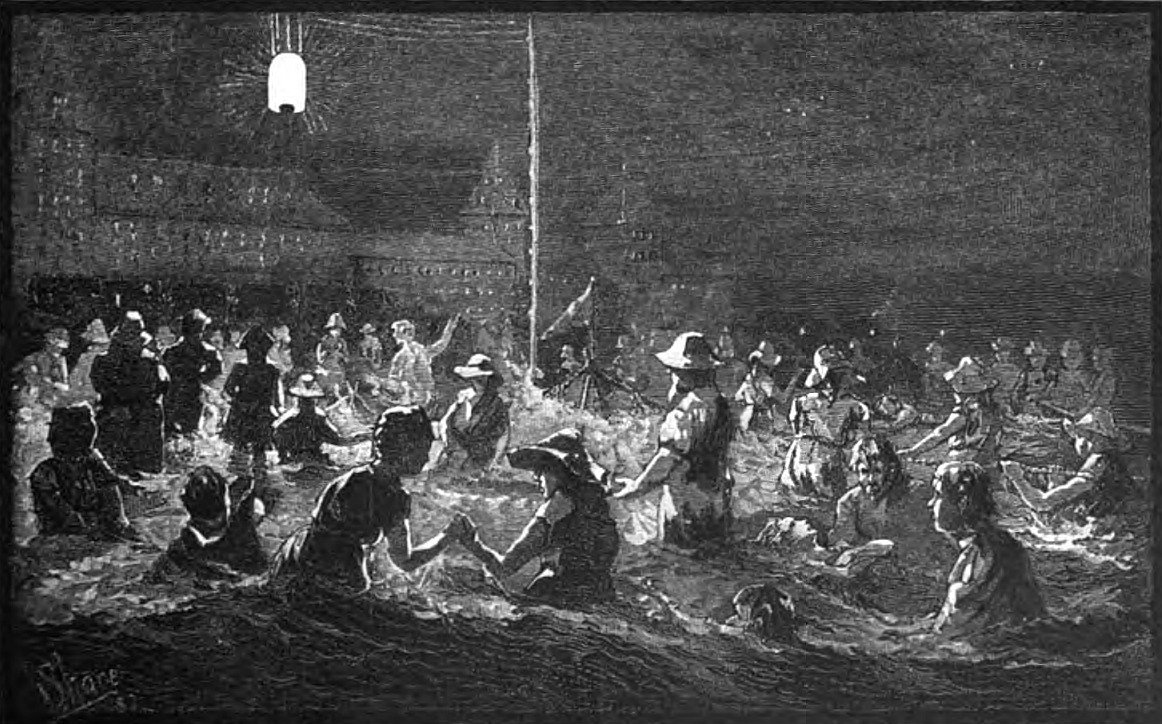

In 1878 Coney Island mounted electric lights on poles so that visitors could play in the surf at night.

“One could take many a long journey and never meet elsewhere with so strange, so truly weird a sight as this,” reported Scribner’s Monthly. “The concentrated illumination falls on the formidable breakers plunging in against the foot of the bridge, and gives them spots of sickly green translucence below and sheets of dazzlingly white foam above. There is a startling spot of foreground and nothing more. A couple who are confident swimmers, possibly a man and his wife, come down the bridge and put off into the cold flood. The woman holds by the man’s belt behind, and he disappears with her into the darkness. A circle disports with hobgoblin glee around a kind of May-pole in the water.”

“Nothing else,” opined the New York Times, “would answer the purpose of those lunatics who persist in bathing after nightfall.”

University of Toronto mathematician Ed Barbeau tells of a Montana student who was asked to find the cost of fencing the perimeter of a rectangular field 132 feet long and 99 feet wide, given that there are 16.5 feet in a rod and that one rod of fencing costs $12.75. The student first worked out five products:

165 × 4 = 660

165 × 7 = 1155

165 × 6 = 990

165 × 9 = 1485

165 × 8 = 1320

He crossed out all but the third and fifth of these and continued:

1275 × 6 = 7650

1275 × 8 = 10200

10200 + 7650 = 17850

17850 + 17850 = 35700

He gave 35700 as the answer. “Indeed the required cost is $357.”

(Ed Barbeau, “Fallacies, Flaws, and Flimflam,” College Mathematics Journal 37:4 [September 2006], 290-292.)

Last year I mentioned Sullivan & Considine’s Theatrical Cipher Code of 1905, a telegraphic code for “everyone connected in any way with the theatrical business.” The idea is that performers, managers, and exhibitors could save money on telegrams by replacing common phrases with short code words:

Filacer – An opera company

Filament – Are they willing to appear in tights

Filander – Are you willing to appear in tights

Filiation – Chorus girls who are shapely and good looking

Filibuster – Chorus girls who are shapely, good looking, and can sing

At the time I lamented that I had only one page. Well, a reader just sent me the whole book, and it is glorious:

Abbacom – Carry elaborate scenery and beautiful costumes

Abbalot – Fairly bristles with hits

Abditarum – This attraction will hurt our business

Addice – Why have not reported for rehearsal

Admorsal – If you do not admit at once will have to bring suit of attachment

Behag – Not the fault of play or people

Bordaglia – Do not advance him any money

Boskop – Understand our agent is drinking; if this is true wire at once

Bosom – Understand you are drinking

Bosphorum – Understand you are drinking and not capable to transact business

Bosser – We are up against it here

Bottle – You must sober up

Bouback – Your press notices are poor

Deskwork – A versatile and thoroughly experienced actress

Despair – Absolute sobriety at all times essential

Detour – Actress for emotional leads

Devilry – Actress with child preferred

Dextral – An actor with fine reputation and proven cleverness

Dishful – Comedian, Swedish dialect

Disorb – Do not want drunkards

Dispassion – Do you object to going on road

Distal – Good dresser(s) both on and off stage

Dormillon – Lady for piano

Drastic – Must be shapely and good looking

Druism – Not afraid of work

Eden – Strong heavy man

Election – What are their complexions

Epic – Does he impress you as being reliable and a hustler

Exclaimer – Are they bright, clever and healthy children

Eyestone – Can you recommend him as an experienced and competent electrician

Faro – A B♭ cornetist

Flippant – Must understand calcium lights

Fluid – Is right up-to-date and understands his business from A to Z

Forester – Acts that are not first class and as represented, will be closed after first performance

Foxhunt – Can deliver the goods

Gultab – The people will not stand for such high prices

Hilbert – State the very lowest salary for which she will work, by return wire

Jansenist – Fireproof theatre

Jinglers – How did the weather affect house

Jolly – Temperature is 15° above zero

There’s also an appendix for the vaudeville circuit:

Kajuit – Trick cottage

Kakour – Grotesque acrobats

Kalekut – Sparring and bag punching act

Kernwort – Troupe of dogs, cats and monkeys

Kluefock – Upside down cartoonist

Koegras – Imitator of birds, etc.

Letabor – Act is poorly staged and arranged

Litterat – The asbestos curtain has not arrived yet

Mallius – How many chairs do you need in the balcony

Meleto – Is the opposition putting on stronger shows than we

The single word “Lechuzo” stands for “Make special effort to mail your report on acts Monday night so as to enable us to determine your opinion of the same, as in many instances yours will be the first house that said act has performed in, and again by receiving your report early it enables us to correct in time any error that may be made regarding performer, salary and efficiency.”

(Thanks, Peter.)

In 1993, reseachers Suzanna Rose and Irene Hanson Frieze asked 135 undergraduates to describe what had happened on their most recent first date:

| Women | Men |

| Groomed and dressed | Picked up date |

| Was nervous | Met parents/roommates |

| (Man:) Picked up date | Left |

| Introduced to parents, etc. | Picked up friends |

| (Man:) Courtly behavior (open doors) | Confirm plans |

| Left | Talked, joked, laughed |

| Confirm plans | Went to movies, show, party |

| Got to know & evaluate date | Ate |

| Talked, joked, laughed | Drank alcohol |

| Enjoyed date | Initiated sexual contact |

| Went to movies, show, party | Made out |

| Ate | Took date home |

| Drank alcohol | Asked for another date |

| Talked to friends | Kissed goodnight |

| Had something go wrong | Went home |

| (Man:) Took date home | |

| (Man:) Asked for another date | |

| (Man:) Told date will call her | |

| (Man:) Kissed date goodnight | |

| Went home |

Of the 20 actions reported by women, 6 were initiated by the man. Of the 15 actions reported by men, none were initiated by the woman.

Thirty-three respondents reported something going wrong. “[O]ne young man had car trouble after picking up his date and was mortified by having to take her back home. Another’s date abandoned her at a party and began to cruise other women, leaving the woman to fend for herself. Embarrassing events were also common. One participant reported having made a fool of herself by throwing the ball backward while bowling; another woman got extremely upset when her date insisted it was ‘love at first sight.'”

“A third type of interruption … was related to perceived violations of gender roles, such as ‘He lost points for not opening my car door’ and ‘We went out to eat later at Pizza Hut and she was a pig.'”

(Suzanna Rose and Irene Hanson Frieze, “Young Singles’ Contemporary Dating Scripts,” Sex Roles 28:9/10, 1993.)

According to Elsdon Smith’s 1967 Treasury of Name Lore, Gwendolyn Kuuleikailialohaopiilaniwailaukekoaulumahiehiekealaoonoaonaopiikea Kekino had a birth certificate to prove her name. Her family called her Piikea.

Albert K. Kahalekula of Wailuku, Hawaii, was a private in the Army in 1957. The K stood for Kahekilikuiikalewaokamehameha. Until Albert’s 29-letter middle name was registered, his brothers had the longest middle names in U.S. military service — each was 22 letters long.

In 1955, restaurant owner George Pappavlahodimitrakopoulous had the longest name in the Lansing, Mich., telephone directory. He made a standing offer of a free meal to anyone who could pronounce the name correctly on the first try (PDF).

Lambros A. Pappatoriantafillospoulous of Chicopee, Mass., joined the Army in 1953, where he was called Mr. Alphabet.

According to Smith, a native policeman in Fiji, British Polynesia, had the name Marika Tuimudremudrenicagitokalauna-tobakonatewaenagaunakalakivolaikoyakinakotamanaenaiivolanikawabualenavalenivolavolaniyasanamaisomosomo, 130 letters long. “The name is said to tell that, with the aid of a northerly wind, Marika’s father sailed from Natewa, on Vanua Levu, to the provincial office at Somosomo, Taveuni, to register the birth of the child.”

The longest name on the Social Security rolls in 1938 was Xenogianokopoulos.

Smith also says that a Fiji Island cricket player bore the 56-letter name Talebulamaineiilikenamainavaleniveivakabulaimakulalakeba.

The oldest Buddhist university in Thailand is Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University.

Above: In 1921 Laurence J. Daly, editor of the Webster Times, proposed lengthening the name of Lake Chaubunagungamaug to Lake Chargoggagoggmanchauggagoggchaubunagungamaugg, which arguably makes it the longest place name in the United States.

Many locals just call it Webster Lake.

All cats are mortal.

Socrates is mortal.

Therefore Socrates is a cat.

— Ionesco, Rhinocéros

How a woman assails a man’s heart, by German map publisher Matthäus Seutter, 1730. Princeton map curator John Delaney explains:

[F]orces are attacking and defending the fortress of Manhood that sits in a frozen, passionless sea. The side of Love, representing the fairer sex, employs four sets of artillery batteries (on the left) to bombard the walls with appeals to vanity, offering delightful surprises, charms, and joys, and plying with tenderness, wishful thinking, and ‘un certain je ne sais quoi.’ Over the walls, naval ships lob such feminine wiles and virtues as beauty, pleasant conversation, gentleness, and ‘regards languissant’ (languishing looks). Love’s forces are camped for the duration (at the lower left), commanded by their general, Cupid.

As the key states, there are also methods for defending and conserving one’s heart against this unrelenting onslaught: memory, prudence, industry, experience (see the lettered outposts along the fortress walls). Ultimately, however, it is a war of attrition. As the trail winding through the fortress and along the coastline proves, the love-struck victim surrenders, retreating, first, to his friends for advice, deliberation, and information, before moving onward to the garden of pleasure and his first encounter with his beloved. … From there, via a subterranean passage, he arrives at the Palace of Love — note the change from fortress to palace — which resides in a sea of peace. Entering is easy, according to the note, but leaving is impossible without losing one’s liberty. Another definition of a prison?

There’s a high-resolution image in Cornell’s rare manuscript collection.

“An object in possession seldom retains the same charm that it had in pursuit.” — Pliny the Younger

In the 1860s, San Francisco’s most popular tourist attraction was not a place but a person: Joshua Norton, an eccentric resident who had declared himself emperor of the United States. Rather than shun him, the city took him to its heart, affectionately indulging his foibles for 21 years. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll consider the reign of Norton I and the meaning of madness.

We’ll also keep time with the Romans and puzzle over some rising temperatures.