perhorresce

v. to shudder at

perhorresce

v. to shudder at

In May 1920, wealthy womanizer Joseph Elwell was found shot to death alone in his locked house in upper Manhattan. The police identified hundreds of people who might have wanted Elwell dead, but they couldn’t quite pin the crime on any of them. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll review the sensational murder that the Chicago Tribune called “one of the toughest mysteries of all times.”

We’ll also learn a new use for scuba gear and puzzle over a sympathetic vandal.

Anthony Burgess based his 1974 novel Napoleon Symphony explicitly on the structure of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3, the Eroica:

There he lies,

Ensanguinated tyrant

O bloody, bloody tyrant

See

How the sin within

Doth incarnadine

His skin

From the shin to the chin.

Overall, Burgess said, he wanted to pursue “one mad idea”: “to give / Symphonic shape to verbal narrative” and to “impose on life … the abstract patterns of the symphonist.”

He dedicated the novel to Stanley Kubrick, hoping that it might form the basis of the director’s long-planned biography of the emperor, but Kubrick decided that “the [manuscript] is not a work that can help me make a film about the life of Napoleon.” Undismayed, Burgess developed it instead into an experimental novel. The critics didn’t like it, but he said it was “elephantine fun” to write.

(From Theodore Ziolkowski, Music Into Fiction, 2017.)

Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer proposed this design for a museum of modern art in Caracas in 1955. He conceived it as a pyramid standing on its apex; the roof would be one vast skylight, and daylight would penetrate the levels inside thanks to spaces at the edges of the floor slabs. There are no side windows so as not to disturb the unity of the slanted walls.

The ground floor would house an auditorium; above that, successively, were a foyer, an exhibition gallery, a mezzanine exhibition space, and the roof, with a sculpture terrace. To free the exhibition halls of load-bearing supports, the mezzanine would be suspended from the four corners of the pyramid by perpendicular tensors.

The whole thing would have perched on a cliff overlooking central Caracas. A change in regime meant that it never got beyond the planning stage.

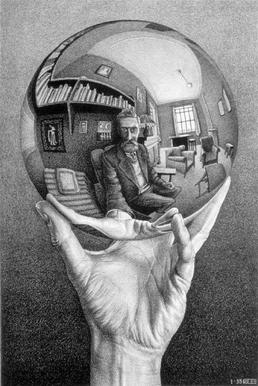

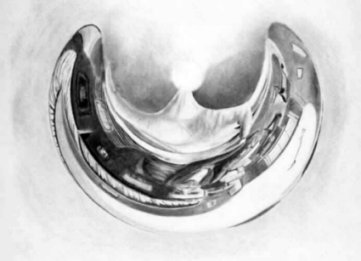

M.C. Escher’s 1935 lithograph Hand With Reflecting Sphere gave artist Kelly M. Houle an idea.

She drew this image in charcoal on a piece of illustration board:

Now when a cylindrical mirror is placed at the center, it produces this reflection:

“When the original image is bent and stretched into a circular swath, the shadows seem to fall in all directions,” she wrote. “When the curved mirror is used to reflect the anamorphic distortion, the forms take on the familiar rules of light and shading that make them seem three-dimensional.”

(Kelly M. Houle, “Portrait of Escher: Behind the Mirror,” in D. Schattschneider and M. Emmer, eds., M.C. Escher’s Legacy, 2003.)

Chicago artist Jerzy Kenar put up this bronze statue in front of his East Village home as a gentle reminder: “I hoped it would motivate dog owners to pick up after their pets.”

When the water’s running it looks even more realistic than this. But both mayor Richard M. Daley and Father Michael Pfleger, pastor of St. Sabina Church, attended the unveiling in 2005.

Kenar says that the statue, at 1003 North Wolcott Avenue, is intended to be whimsical, and that most visitors take it in that spirit, posing and even drinking from the fountain. “Only one little old lady didn’t get the joke,” he said.

He also designed the Black History Fountain near St. Sabina … so this one is sometimes called his “number two fountain.”

(From Greg Borzo, Chicago’s Fabulous Fountains, 2017.)

Western Kentucky University geoscientist John All was traversing Nepal’s Mount Himlung in May 2014 when the ice collapsed beneath him and he fell into a crevasse, dislocating his shoulder and breaking some ribs. He landed on a ledge, but now he faced a 70-foot climb back to the surface alone without the use of his right arm or upper leg.

“That’s when I pulled my research camera out and started talking to myself about all my options,” he told National Geographic. “I take photos of everything I do because, if I’m working in Africa and I need to recall a detail, that’s going to be the best way to do it. I was also thinking about my mom and my friends and family and realized that just talking wouldn’t convey what was happening to me nearly as well. So I started recording things.”

“It probably took me four or five hours to climb out,” he said. “I kept moving sideways, slightly up, sideways, slightly up, until I found an area where there was enough hard snow that I could get an ax in and pull myself up and over. I knew that if I fell at any time in that entire four or five hours, I, of course, was going to fall all the way to the bottom of the crevasse. Any mistake, or any sort of rest or anything, I was going to die.”

After reaching the top he rolled as much as walked back to his tent, called for help, and waited 16 hours for a helicopter to arrive. He wrote later, “I had dug myself out of my own grave.”

A poem by Louis Phillips: “If the Modern Artist Ralph Goings Had Met the Poet E.E. Cummings”:

Goings?

Cummings?

Cummings,

Goings.

Goings,

Cummings.

Going,

Goings?

Yep.

Cummings,

Going?

Nope.

In talking about superheroes, these sentences seem natural and right:

(la) Clark Kent went into the phone booth and Superman came out.

(2a) Superman leapt over tall buildings.

(3a) Superman is more successful with women than Clark Kent.

(4a) Batman wears a mask.

But these seem inappropriate or wrong:

(lb) Clark Kent went into the phone booth and Clark Kent came out.

(2b) Clark Kent leapt over tall buildings.

(3b) Clark Kent is more successful with women than Clark Kent.

(4b) Bruce Wayne wears a mask.

Why is this? If we know that Superman is Clark Kent, then those terms should be interchangeable — a statement about Superman is a statement about Clark Kent; they’re the same person.

“At least in some conversational scenarios, utterances of (la)-(4a) strike us as true, and utterances of (lb) (4b) appear to be false,” writes University of Nottingham philosopher Stefano Predelli. “(3a), for instance, seems just the right thing to say when discussing women’s fascination with men in blue leotard; utterances of (3b), on the other hand, seem trivially false. Similarly, during a discussion of why the famed superhero never engages in extraordinary feats when playing the part of the timid journalist, utterances of (2a) seem unobjectionable, but utterances of (2b) will not do.” Why?

(Stefano Predelli, “Superheroes and Their Names,” American Philosophical Quarterly 41:2 [April 2004], 107-123.)