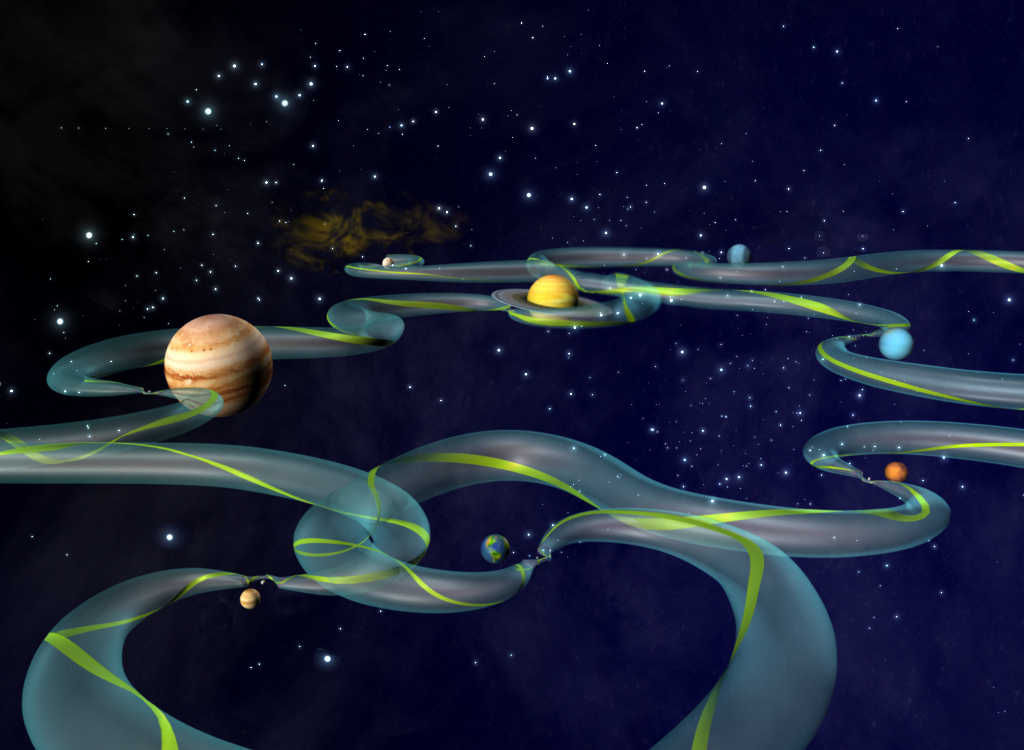

A thrifty space traveler can explore the solar system by following the Interplanetary Transport Network, a series of pathways determined by gravitation among the various bodies. By plotting the course carefully, a navigator can choose a route among the Lagrange points that exist between large masses, where it’s possible to change trajectory using very little energy.

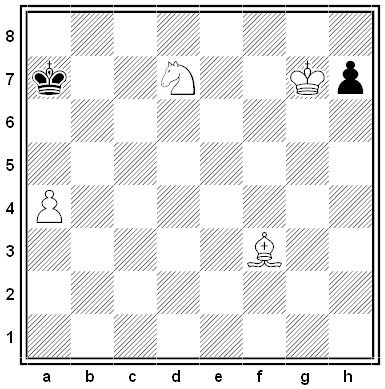

In the NASA image above, the “tube” represents the highway along which it’s mathematically possible to travel, and the green ribbon is one such route.

The good news is that these paths lead to some interesting destinations, such as Earth’s moon and the Galilean moons of Jupiter. The bad news is that such a trip would take many generations. Virginia Tech’s Shane Ross writes, “Due to the long time needed to achieve the low energy transfers between planets, the Interplanetary Superhighway is impractical for transfers such as from Earth to Mars at present.”