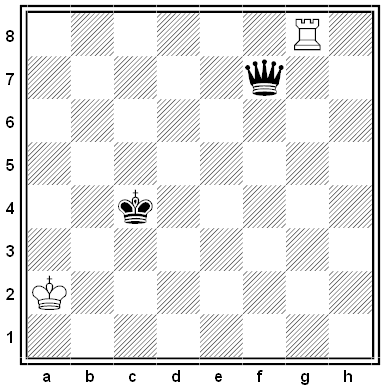

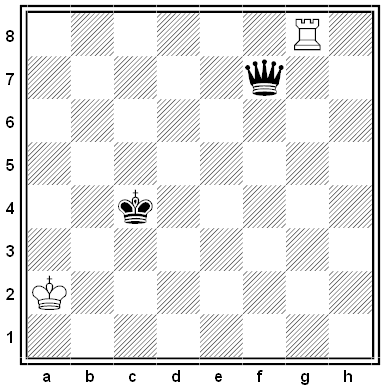

A “maximummer-selfmate” by T.R. Dawson, from 1934. White wants to force Black to checkmate him, and Black always makes the geometrically longest move available to him. How can White accomplish his goal in three moves?

A “maximummer-selfmate” by T.R. Dawson, from 1934. White wants to force Black to checkmate him, and Black always makes the geometrically longest move available to him. How can White accomplish his goal in three moves?

Another puzzle from Kendall and Thomas’ Mathematical Puzzles for the Connoisseur (1971):

Take three consecutive positive integers and cube them. Add up the digits in each of the three results, and add again until you’ve reached a single digit for each of the three numbers. For example:

463 = 97336; 9 + 7 + 3 + 3 + 6 = 28; 2 + 8 = 10; 1 + 0 = 1

473 = 103823; 1 + 0 + 3 + 8 + 2 + 3 = 17; 1 + 7 = 8

483 = 110592; 1 + 1 + 0 + 5 + 9 + 2 = 18; 1 + 8 = 9

Putting the three digits in ascending order will always give the result 189. Why?

altivolant

adj. high-flying

aspectable

adj. capable of being seen, visible

terriculament

n. a source of fear

John Lithgow’s eyes pop out of his head momentarily at the climax of “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” the final segment in Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983). In the segment, a remake of the famous television episode from 1963, Lithgow plays a nervous air passenger who discovers a gremlin on the wing of his plane. At the moment when he lifts the shade, the edit shows the monster for 17 frames, then Lithgow’s face for 10 frames, then the monster for 42 frames, and then a 5-frame shot of Lithgow’s head incorporating the eye-popping effect.

Of these 5 frames, the first three show a wild-eyed Lithgow, the fourth shows bulging eyes, and the fifth is shown below. “This 5-frame sequence is on the screen for 1/5 second, but the most distorted image is only visible for 1/24 second,” writes William Poundstone in Bigger Secrets. “Blink at the wrong time, and you miss it. But if you watch the shot carefully at normal speed, the sequence is detectable. Lithgow’s eyes seem to inflate with an accelerated, cartoon-like quality.”

Here’s the frame:

“If you think that you can think about a thing, inextricably attached to something else, without thinking of the thing it is attached to, then you have a legal mind.” — Thomas Reed Powell

A lawyer advertised for a clerk. The next morning his office was crowded with applicants — all bright, many suitable. He bade them wait until all should arrive, and then ranged them in a row and said he would tell them a story, note their comments, and judge from that whom he would choose.

‘A certain farmer,’ began the lawyer, ‘was troubled with a red squirrel that got in through a hole in his barn and stole his seed corn. He resolved to kill the squirrel at the first opportunity. Seeing him go in at the hole one noon, he took his shot gun and fired away; the first shot set the barn on fire.’

‘Did the barn burn?’ said one of the boys.

The lawyer without answer continued: ‘And seeing the barn on fire, the farmer seized a pail of water and ran to put it out.’

‘Did he put it out?’ said another.

‘As he passed inside, the door shut to and the barn was soon in flames. When the hired girl rushed out with more water’ —

‘Did they all burn up?’ said another boy.

The lawyer went on without answer:–

‘Then the old lady came out, and all was noise and confusion, and everybody was trying to put out the fire.’

‘Did any one burn up?’ said another.

The lawyer said: ‘There that will do; you have all shown great interest in the story.’ But observing one little bright-eyed fellow in deep silence, he said: ‘Now, my little man, what have you to say?’

The little fellow blushed, grew uneasy, and stammered out:–

‘I want to know what became of that squirrel; that’s what I want to know.’

‘You’ll do,’ said the lawyer; ‘you are my man; you have not been switched off by a confusion and a barn burning, and the hired girls and water pails. You have kept your eye on the squirrel.’

— Ballou’s Monthly Magazine, February 1892

Poet Brendan Behan began his career as a housepainter. While in Paris, he was asked to paint a sign on the window of a café to attract English-speaking tourists. He painted:

Come in, you Anglo-Saxon swine

And drink of my Algerian wine.

‘Twill turn your eyeballs black and blue

And damn well good enough for you.

“At least I got paid for it,” he said later. “But I ran out of the place before the patron could get my handiwork translated.”

(From his wife Beatrice’s My Life With Brendan, 1973.)

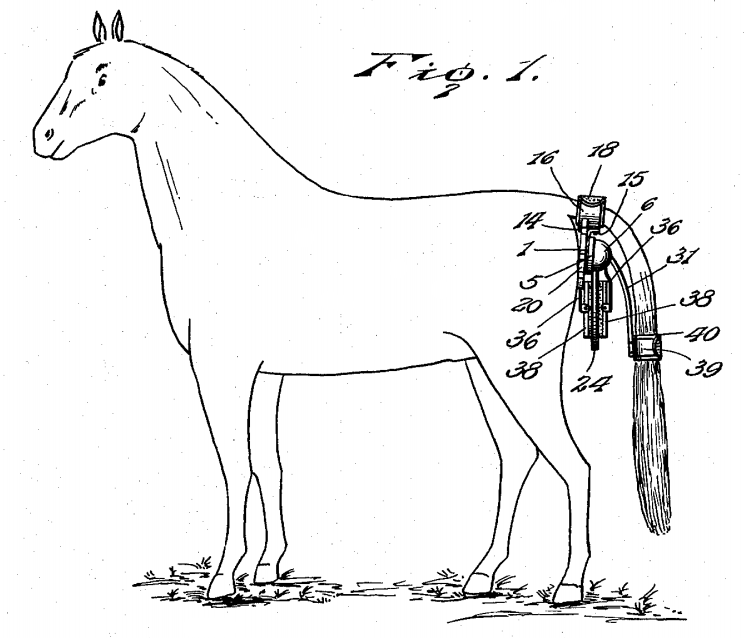

In 1936, J.E. Torbert patented a taillight for horses:

When a person is riding a horse along a road at night and an automobile approaches the horse from the rear, the signals will be illuminated by reflecting light from the headlights of the automobile and thus permit the driver of the automobile to see that there is a horse ahead of him and eliminate danger of the automobile striking and injuring the horse.

Simple enough. By that time we already had headlights for horses. What’s next?

For 500 years it was thought that Geoffrey Chaucer had written The Testament of Love, a medieval dialogue between a prisoner and a lady.

But in the late 1800s, British philologists Walter Skeat and Henry Bradshaw discovered that the initial letters of the poem’s sections form an acrostic, spelling “MARGARET OF VIRTU HAVE MERCI ON THINUSK” [“thine Usk”].

It’s now thought that the poem’s true author was Thomas Usk, a contemporary of Chaucer who was accused of conspiring against the duke of Gloucester. Apparently he had written the Testament in prison in an attempt to seek aid — Margaret may have been Margaret Berkeley, wife of Thomas Berkeley, a literary patron of the time.

If it’s aid that Usk was seeking, he never found it: He was hanged at Tyburn in March 1388.

A puzzle by Matt Parker of standupmaths:

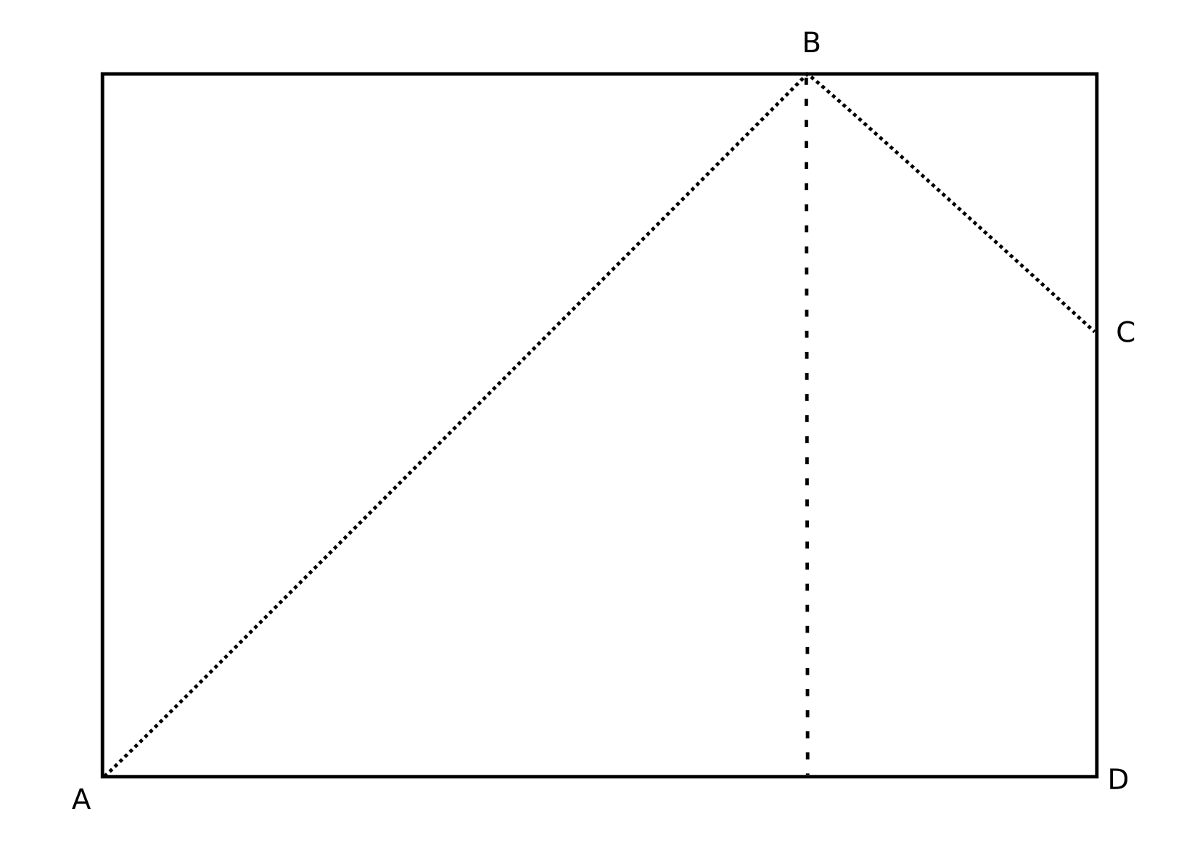

The standard paper size A4 has dimensions in the ratio . Hold a piece of A4 paper horizontally, as shown, and fold down the top left corner to meet the other side, creating fold AB, as if you were going to make a paper square. Then fold down the top right corner to meet the edge of this 1 × 1 square (making fold BC).

The perimeter of the original sheet was . What is the perimeter of the folded shape (the quadrilateral ABCD above)?

I’ll honor Matt’s request not to reveal the answer, but here’s a clue: The shape ABCD is a kite. See Matt’s video for a more visual explanation and a non-spoilery way to tell whether you have the right answer.

(Thanks to Dave Lawrence for the tip and the diagram.)

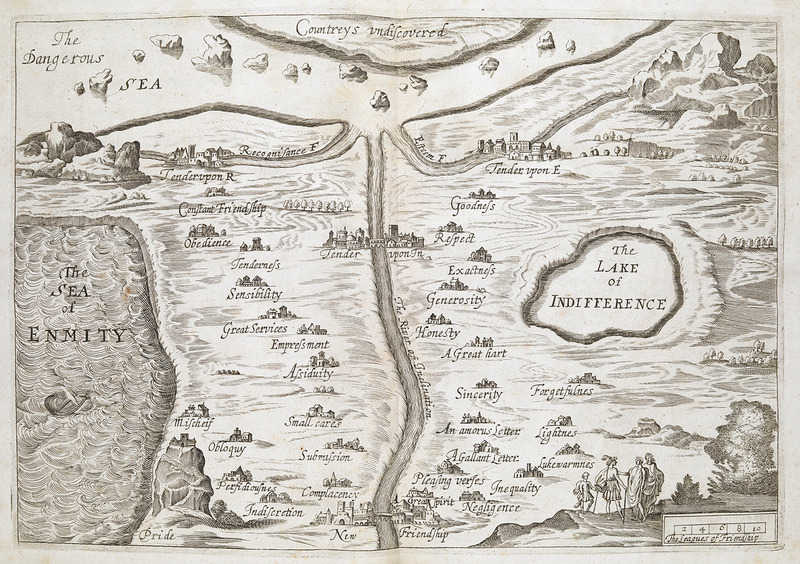

Here’s why your relationships keep falling apart — finding the right course is almost impossible. The French noblewoman Madeleine de Scudéry devised this map of the “Land of Tenderness” in 1653, for her romance Clelia. A couple starting at New Friendship, at the bottom, can take any of four roads. Two of them stay safely near the River of Inclination: One of these passes through Complacency, Submission, Small Cares, Assiduity, Empressment, Great Services, Sensibility, Tenderness, Obedience, and Constant Friendship to reach “Tender Upon Recognisance”; the other passes through Great Spirit, Pleasing Verses, A Gallant Letter, An Amorous Letter, Sincerity, A Great Heart, Honesty, Generosity, Exactness, Respect, and Goodness to reach “Tender Upon Esteem.” But there are two more dangerous outer roads: One passes through Indiscretion, Perfidiousness, Obloquy, and Mischief to end in the Sea of Enmity; the other through Negligence, Inequality, Lukewarmness, Lightness, and Forgetfulness to reach the Lake of Indifference. And even lovers who reach a happy outcome may go too far, passing into the Dangerous Sea and perhaps beyond it into Countreys Undiscovered.

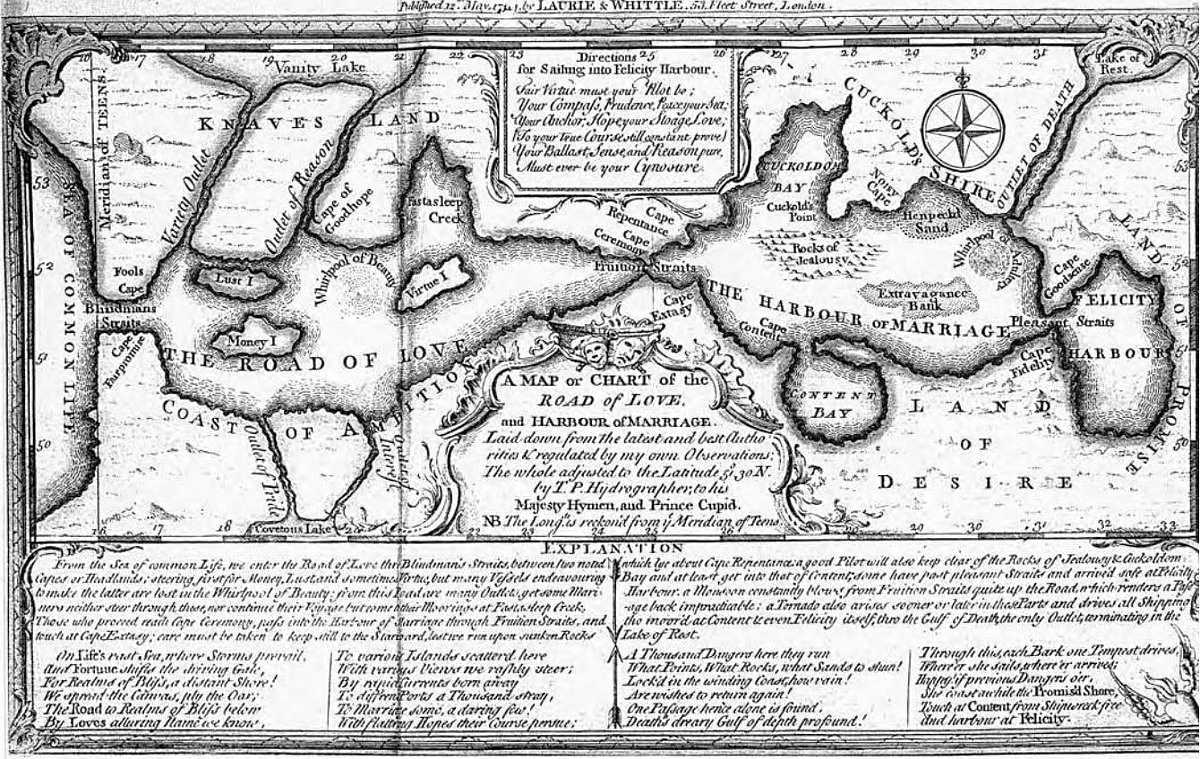

Even worse is this vision, a “Map or Chart of the Road of Love, and Harbour of Marriage” published by “T.P. Hydrographer, to his Majesty Hymen, and Prince Cupid” in 1772. The traveler has to find the way from the Sea of Common Life at left to Felicity Harbour and the Land of Promise at right, and the only way to get there is by the Harbour of Marriage, in which lurk Henpecked Sand and the disastrous Whirlpool of Adultery. The explanation at the bottom describes the treacherous course:

From the Sea of Common Life, we enter the Road of Love thro’ Blindmans Straits, between two noted Capes or Headlands; steering first for Money, Lust, and sometimes Virtue, but many Vessels endeavouring to make the latter are lost in the Whirlpool of Beauty; from this Road are many outlets, yet some Mariners neither steer through these, nor continue their Voyage but come to their Moorings at Fastasleep Creek. Those who proceed reach Cape Ceremony, pass into the Harbour of Marriage through Fruition Straits and touch at Cape Extasy; care must be taken to keep still to the Starboard, lest we run upon sunken Rocks which lye about Cape Repentance; a good Pilot will also keep clear of the Rocks of Jealousy & Cuckoldom Bay and at least get into that of Content, some have past pleasant Straits and have arrived safe at Felicity Harbour, a Monsoon constantly blows from Fruition Straits quite up the Road, which renders a Passage back impracticable; a Tornado also arises sooner or later in those Parts and drives all Shipping tho moor’d at Content & even Felicity itself, thro the Gulf of Death, the only Outlet, terminating in the Lake of Rest.

The map provides some general advice: “Your Virtue must your Pilot be; Your Compass, Prudence, Peace your Sea; Your Anchor, Hope; your Sto[w]age, Love; (To your true Course still constant prove) Your Ballast, Sense, and Reason pure, Must ever be your Cynosure.”

(From Ashley Baynton-Williams, The Curious Map Book, 2015.)

German playwright Ernst Toller was arrested for socialist activities in 1919. His 1937 collection of letters from prison, Look Through the Bars, includes this memory:

Stadelheim 1919

Dear ——,

We are a hundred men here in prison, separated from our wives for months. Every conversation between any two men always ends in the same way — women.

The high walls prevent any view. Within the walls is a small hut. It was, we heard, some sort of wash-house, which was not used. One day one of us saw that the shutters of the hut were opened. He saw two women at work. One stayed in the wash-house, the other went away and locked the door. Soon we knew all. The two women were a wardress and a prisoner, who was to be released in a short time. She had been sentenced to eight years’ imprisonment for child-murder. She had already served five years; in a few weeks’ time she was to be pardoned.

It would be too complicated to tell you how we contrived to exchange notes with the girl. First playful and harmless ones, then feverish, passionate and confused ones. Everything which, in that closed-in existence, had come in dreams, wishes and fantasies went out to that woman. One morning she gave us a signal. We were to stand near the window at a certain hour.

Impossible to describe what happened. The woman opened her dress and stood naked at the window. She was surprised and taken away. We never saw her again. But we learned that the pardon had been annulled.

Never has a woman moved me so much as that little prisoner, who, in order to make men happy for a few seconds (in a very questionable way) suffered with unsophisticated wisdom three more years in prison.