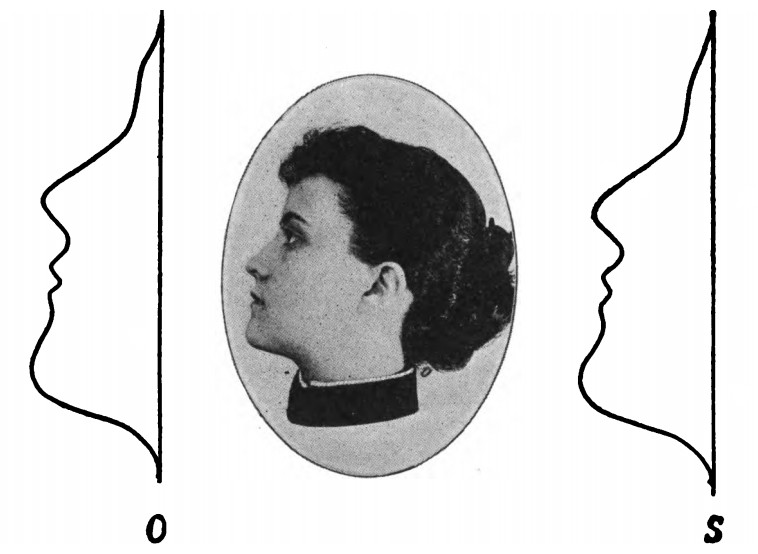

In his 1916 book The Science of Musical Sounds, Dayton Clarence Miller uses harmonic analysis to convert the line of a woman’s profile (left) into an equation of 18 terms. Then he uses this equation to reproduce the profile synthetically (right). “If mentality, beauty, and other characteristics can be considered as represented in a profile portrait,” he writes, “then it may be said that they are also expressed in the equation of the profile.”

He repeats the synthesized profile to produce a waveform:

“In this sense beauty of form may be likened to beauty of tone color, that is, to the beauty of a certain harmonious blending of sounds.”

In Noise, Water Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts, Douglas Kahn writes, “The simple beauty of the female expressed in the line thus becomes also the simple beauty of mathematics, graphic representation, and instrumentation, let alone mediation and reproduction, involved in the production of the equation and profile. Thus, we move beyond Lord Kelvin’s fascination with a beauty of mathematics to a fascination with a mathematics of beauty.”