GIROLAMO SAVONAROLA alternates vowels and consonants.

(Thanks, Joseph.)

GIROLAMO SAVONAROLA alternates vowels and consonants.

(Thanks, Joseph.)

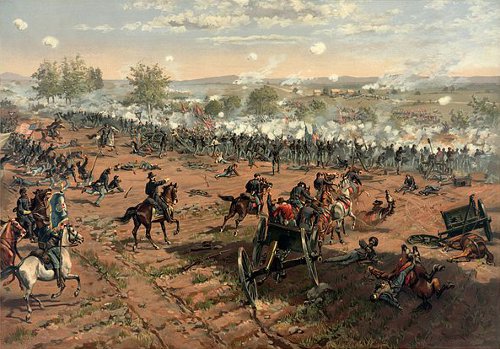

On June 23, 1858, the Catholic Church removed 6-year-old Edgardo Mortara from his family in Bologna. The reason they gave was surprising: The Mortaras were Jewish, and Edgardo had been secretly baptized. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll tell the story of little Edgardo and learn how his family’s plight shaped the course of Italian history.

We’ll also hear Ben Franklin’s musings on cultural bigotry and puzzle over an unexpected soccer riot.

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs is still paying a pension earned by a Civil War soldier.

Union infantryman Mose Triplett was 19 at the war’s end in 1865. In the 1920s he married a woman nearly 50 years his junior, and they had a daughter, Irene, in 1930, when Mose was 83 and his wife was 34.

Irene Triplett, now 85 years old and the last child of any Civil War veteran still on the VA benefits rolls, lives today in a nursing home in Wilkesboro, N.C. She collects $73.13 each month through the pension her father earned for her in 1865.

(Thanks, Tom.)

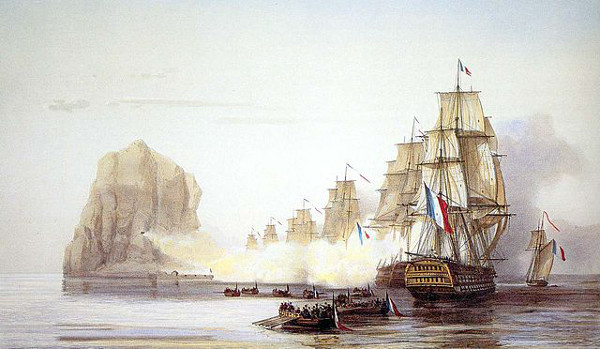

Ordered to blockade Martinique in 1803, Commodore Sir Samuel Hood covered an island with guns and declared it a sloop-of-war. Perched 175 meters above the sea, the guns denied all entrance to Fort-de-France, the island’s main port, for 17 months.

The British Royal Navy still regards “HMS Diamond Rock” as being in commission — when passing the island, personnel on Royal Navy ships stand at attention and salute the rock.

Since that time, a naval establishment on land has been referred to as a “stone frigate.”

In 1985, as the U.S. Senate was considering whether to declare the rose America’s national flower, Sen. Howell Heflin (D-Ala.) read out a seven-verse poem in support of the measure:

Marigolds and dogwood,

Camellias and more,

All flowers are beautiful

And made to adore.

But today there are deficits,

And farm bills and trade,

Aren’t these the subjects

On which decisions should be made?

Still, if on a nation’s flower

A few moments we spend,

We might be refreshed and

Come down to Earth again.

Besides, to select a flower

As America’s might not be bad,

Because I sure don’t want

To make the garden clubs mad.

But all flowers are delicate.

Each can refresh and amuse,

And that is the reason

I feel no flower should lose.

Still the rose is universal,

Its support has a strong voice,

So there should be no question

That the rose is the choice.

So let us raise our voice and

Proclaim with all our power

That the rose is more than beautiful —

It is “America’s Flower.”

Sen. Bennett Johnston (D-La.), who sponsored the joint resolution, replied in kind:

Roses are red,

Violets are blue,

Heflin should be

A co-sponsor of this bill too.

Ronald Reagan signed the measure into law the following year.

(Thanks, Sam.)

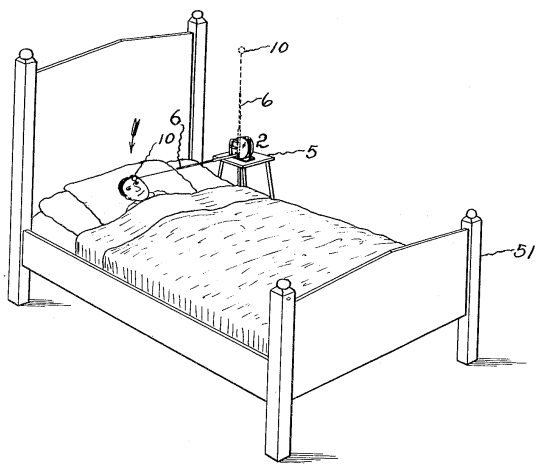

In 1919 John D. Humphrey patented an alarm clock designed “to impart a blow to an individual.”

There’s no bell. At the appointed hour, the clock drops a rubber ball onto your face to awaken you “without unnecessary shock.”

Humphrey intended it chiefly for the deaf. He described it as “simple in construction and positive and certain in action.”

“To the memory of Miss Emily Kay, cousin to Miss Ellen Gee, of Kew, who died lately at Ewell, and was buried in Essex.”

Sad nymphs of U L, U have much to cry for,

Sweet M L E K U never more shall C!

O S X maids! come hither and D 0,

With tearful I, this M T L E G.

Without X S she did X L alway,

Ah me! it truly vexes 1 2 C

How soon so D R a creature may D K,

And only leave behind X U V E!

Whate’er 1 0 to do she did discharge,

So that an N M E it might N D R:

Then why an S A write? — then why N

Or with my briny tears B D U her B R?

When her Piano-40 she did press,

Such heavenly sounds did M N 8, that she

Knowing her Q, soon 1 U 2 confess

Her X L N C in an X T C.

Her hair was soft as silk, not Y R E,

It gave no Q, nor yet 2 P to view:

She was not handsome; shall I tell U Y?

U R 2 know her I was all S Q.

L 8 she was, and prattling like a J;

How little, M L E! did you 4 C,

The grave should soon M U R U, cold as clay,

And you shall cease to be an N T T!

While taking T at Q with L N G,

The M T grate she rose to put a :

Her clothes caught fire — no 1 again shall see

Poor M L E, who now is dead as Solon.

O L N G! in vain you set at 0

G R and reproach for suffering her 2 B

Thus sacrificed; to J L U should be brought,

Or burnt U 0 2 B in F E G.

Sweet M L E K into S X they bore,

Taking good care the monument 2 Y 10,

And as her tomb was much 2 low B 4,

They lately brought fresh bricks the walls to 10.

— Horace Smith, in A Budget of Humorous Poetry, 1866

(This is a bit more recondite than the Ellen Gee poem. “D 0” is decipher, “1 0 to” is one ought to, N is enlarge, 10 is heighten, and “X U V E,” I am pleased to understand, is exuviae, “an animal’s cast or sloughed skin.” Let’s hope it stopped here.)

A city has 10 bus routes. Is it possible to arrange the routes and bus stops so that if one route is closed it’s still possible to get from any one stop to any other (possibly changing buses along the way), but if any two routes are closed, there will be at least two stops that become inaccessible to one another?

When Michael Hordern took on the role of King Lear, he asked John Gielgud whether he had any advice to help him get through the run.

“Yes,” Gielgud said. “Get a small Cordelia.”

In 1895, hoping to marry sound and pictures, William Kennedy Laurie Dickson played a violin into a phonograph horn in Thomas Edison’s experimental film studio, and the sound was recorded on a wax cylinder.

The experiment went well, but the team made no attempt to unite sound and image at the time. The film portion remained well known, but the wax cylinder drifted into another archive and was rediscovered only in the 1960s. It wasn’t until 2000 that film editor Walter Murch succeeded in adding the music to the long-famous fragment, and Dickson’s violin could finally be heard.

The vignette, now the oldest known piece of sound film, shows that sound was not a late addition to moviemaking, film preservationist Rick Schmidlin told the New York Times. “This teaches that sound and film started together in the beginning.”