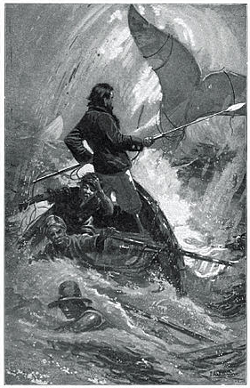

How does Ahab find Moby-Dick? On more than 11 occasions in Melville’s novel we are given cardinal points, the accurate location of well-known cruising grounds, and changes in the ship’s direction as the Pequod follows a “zig-zag world-circle” in search of the great white whale. But we are never told how he hopes to find it, a task that seems flatly impossible.

In writing the book, Melville consulted maps, guidebooks, charts, and logbooks to lay out a route typical of a three-year whaling voyage. Ahab, as an experienced captain, might have known the migratory patterns of sperm whales, their feeding grounds, the ocean currents, and the locations of previous sightings. “But even with this seasoned knowledge, he is not guaranteed to track down an entire pod of whales, let alone one eccentric loner,” writes Eric Bulson in Novels, Maps, Modernity (2007).

Ishmael notes that “though Moby-Dick had in a former year been seen, for example, on what is called the Seychelle ground in the Indian ocean, or Volcano Bay on the Japanese coast; yet it did not follow, that were the Pequod to visit either of those spots at any subsequent corresponding season, she would infallibly encounter him there. … For as the secrets of the currents in the seas have never yet been divulged, even to the most erudite research; so the hidden ways of the Sperm Whale when beneath the surface remain, in great part, unaccountable to his pursuers.”

At one point Melville contends that the Pequod‘s circumnavigating route “would sweep almost all the known Sperm Whale cruising grounds of the world,” a conceit that the New York Albion called “more than sufficient motive” to justify the otherwise “intolerably absurd” idea of “a nautical Don Quixote chasing a particular fish from ocean to ocean.”

But even Ahab himself seems helpless in his task until the whale’s unexplained appearance at the novel’s end. In a dramatic address to the sun, he says, “Thou tellest me truly where I am — canst thou cast the least hint where I shall be? Or canst thou tell where some other thing besides me is this moment living? Where is Moby-Dick?”