Vacancies

Between 1937 and 1939, Nazi Germany built a colossal beach resort on the island of Rügen in the Baltic Sea. Its scale was enormous: Meant to host 20,000 holiday-makers at a time in shifts of 10 days, the six-story edifice of 10,000 double rooms stretches for 4.5 kilometers, requiring almost an hour to walk its length. At the end of the war seven of a planned eight blocks and part of a main square had been completed. Since then it’s housed small-scale projects, including a youth and a family hostel, a skating hall, a theatre, workshops, museums, art galleries, secondhand shops, and a disco. Today five of the blocks have been developed as apartments and a new hostel, while the remaining three lie in ruins.

Until four years ago, fully 1 percent of Greenland’s population was housed in a single building, Blok P. Erected in the 1960s, it was five stories high and stretched 200 meters, the largest construction project in the Kingdom of Denmark, with one end boasting the world’s largest flag of Greenland. But its poor design made the building a difficult and depressing home for its residents, and it was demolished in 2012.

Before the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974, the tourist district of Varosha was the nation’s premier vacation destination, with high-rise hotels, shopping centers, restaurants, and nightclubs. With the invasion, the entire population of 39,000 fled, leaving behind an opulent ghost town. Since then it’s been fenced off, accessible only by the Turkish military and United Nations personnel. Negotiations continue, but after 40 years of mounting disrepair it’s not clear how much of it might still be salvaged.

(Thanks, Matthias and Steve.)

A Splitting Headache

Tom has a crystal ball that shows him the future. One day it shows him a bomb going off in the city. He alerts the authorities, who disable the bomb, saving millions of people. Tom is glad, but he wonders: How can this outcome be logically consistent with the future that the crystal ball had shown him? In that future he saw millions of people die, but in this future they’re still alive. He realizes that when he contacted the authorities the timeline must have split in two. In the original timeline, the bomb went off just as the crystal ball had foretold, and the city’s population did die. But in this new timeline, the authorities defused the bomb and everyone lived.

This understanding seems to explain what has happened, but it leaves a worrying subjective question. If there are two timelines then there are two Toms, both sharing the same history and presumably each realizing that two instances of his identity now exist. “We are familiar with physical things splitting into two, and can accept in principle that they could even be duplicated,” writes Western University philosopher John L. Bell. “But it is extremely difficult to make sense of the idea that an individual consciousness can be so split.”

The doomed Tom might ask himself, “Why am I the doomed Tom?” Objectively the answer is that he’s the Tom who failed to alert the authorities to the coming catastrophe. “But from a subjective point of view he can ask: why was I the Tom who failed to act? Why couldn’t I have been the saved Tom? There seems to be no satisfactory answer to this question.”

In his Philosophy of Mathematics and Natural Science, mathematician Hermann Weyl notes that Leibniz thought he had resolved the tension between freedom and predestination by letting God consider the infinite number of possible universes and assign existence to one of them. “This solution may objectively be sufficient,” Weyl wrote, “but it is shattered by the desperate outcry of Judas, ‘Why did I have to be Judas?'”

(From Oppositions and Paradoxes, 2016.)

Immaterial

British author Sarah Caudwell wrote four mystery novels without revealing the main character’s gender.

Like Caudwell herself, sleuth Hilary Tamar taught law at Oxford and was witty, erudite, and incisive. In the four novels — Thus Was Adonis Murdered, The Shortest Way to Hades, The Sirens Sang of Murder, and The Sybil in Her Grave — Tamar acts as mentor to four barristers in “legal whodunits” that revolve around the intricacies of the British legal system. Tamar, who serves as both storyteller and detective, writes in the first person, often communicates with the other characters by letter, and is addressed directly when present:

‘So you see, Hilary,’ said Selena, ‘no one’s on holiday. Except Julia, of course. She should be in Venice by now.’

‘Julia?’ I said, much astonished. ‘You haven’t let Julia go off on her own to Venice, surely?’

‘Am I,’ asked Selena, ‘Julia’s keeper?’

‘Yes,’ I said, rather severely, for her attitude seemed to me irresponsible.

“Others speak to Hilary or use the name — one never knows for sure whether Hilary is woman or man,” notes Sally McConnell-Ginet in Greville G. Corbett’s The Expression of Gender. “Caudwell manages this so skillfully that people reading the novels do not always notice the absence of definitive gendering of Hilary: they sometimes mentally provide she or he on the basis of whichever familiar gender assumptions happen to attract their attention.”

“Very few people seemed to notice that there was any doubt,” Caudwell said. “Usually they referred to Hilary as certainly female or certainly male. It’s now mentioned in the jacket copy and, having been tipped off, readers become very angry at me for not resolving it at the end of the book.” But she had determined never to reveal Tamar’s gender. “I think Hilary is sort of a quintessential Oxford don,” she said. “I don’t really regard Oxford dons as being determined by gender.”

This never bothered her fans, who love the books for their brilliance and humor. Writing in The New York Times Book Review, Newgate Callendar praised Caudwell’s “polished, stylized prose,” “a kind of English that has not been around since the days of Oscar Wilde.” Robert Bork once said, “In my opinion, there can’t be too many Sarah Caudwell novels.” Alas, there are only four — she passed away in 2000.

Smoothly

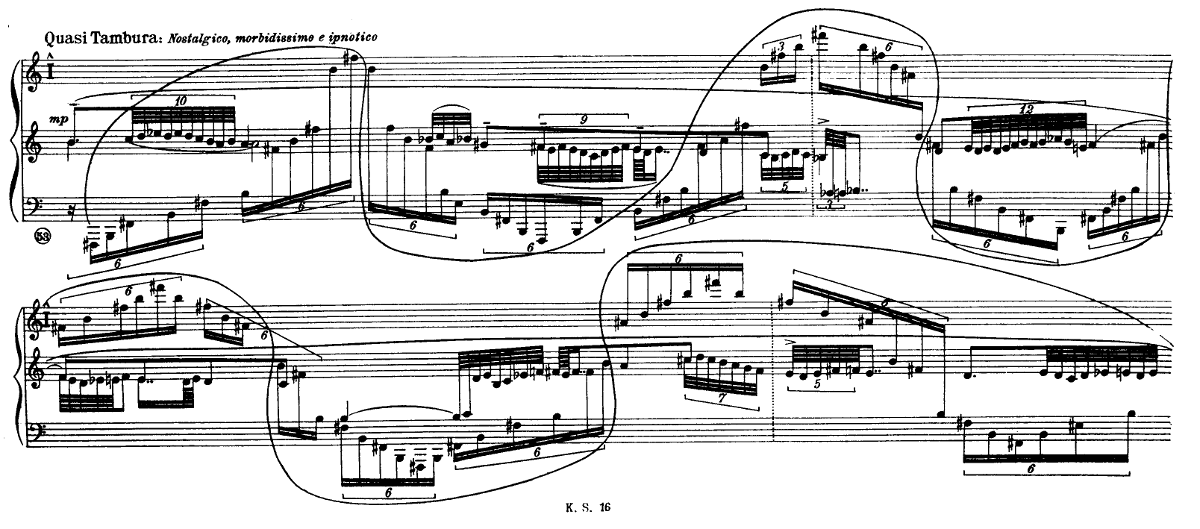

This is an excerpt from Kaikhosru Sorabji’s Opus Clavicembalisticum of 1930. The snaky line running through it is a slur (!) encompassing the whole complex passage.

Indiana University information scientist Donald Byrd observes, “It has a total of 10(!) inflection points; it spans three systems, repeatedly crosses three staves (this is also the most staves within a system for any slur I know of), and goes slightly backwards — i.e., from right to left — several times.”

More at Byrd’s Gallery of Interesting Music Notation.

Harms and the Man

The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) is a list of more than 10,000 diseases and maladies that patients might present. The medical community uses it for recordkeeping — for example, a patient admitted to the hospital with whooping cough would be logged in the database with code A37. Reader Will Beattie sent me a list of some of the stranger complaints on the list:

- Urban rabies – A821

- Lobster-claw hand, bilateral – Q7163

- Fall into well – W170

- Complete loss of teeth, unspecified cause – K0810

- Pecked by turkey – W6143

- O’nyong-nyong fever – A921

- Hang glider explosion injuring occupant – V9615

- Contact with hot toaster – X151

- Major anomalies of jaw size – M260

- Intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) – N3642

- Underdosing of cocaine – T405X6

- Prolonged stay in weightless environment – X52

Will says his favorite so far is “Burn due to water skis on fire – V9107.” It’s a dangerous world,” he writes. “Be safe out there.”

Related: Each year the Occupational Safety and Health Administration publishes a list of workplace deaths, with a brief description of each incident:

- Worker died when postal truck became partially submerged in lake.

- Worker was caught between rotating drum and loading hopper of a ready-mix truck.

- Worker fatally engulfed in dry cement when steel storage silo collapsed.

- Worker on ladder struck and killed by lightning.

- Worker was pulled into a tree chipper machine.

- Worker was caught between two trucks and crushed.

- Worker died when his head was impaled by metal from the drive section of a Ferris wheel. The employee slipped after acknowledging he was clear and the wheel began to turn, trapping his head.

- Worker was draining a tank; one of the employees climbed to the top of the tank and lit a cigarette and waved it over the opening in the tank. The tank exploded, killing the worker.

- Worker was kicked by an elephant.

- Sheriff Deputy was walking through the woods, working a cold case, and fell 161 feet into a sink hole.

It’s hard to pick the worst one. “Worker was operating a skid-steer cleaning out a dairy cattle barn near an outdoor manure slurry pit. The skid-steer and the worker fell off the end of the push-off platform into the manure slurry pit, trapping the worker in the vehicle. Worker died of suffocation due to inhalation of manure.”

Practicalities

If 6 cats can kill 6 rats in 6 minutes, how many will be needed to kill 100 rats in 50 minutes?

It’s easy enough to work out that the answer is 12, but consider what this means. “When we come to trace the history of this sanguinary scene through all its horrid details, we find that at the end of 48 minutes 96 rats are dead, and that there remain 4 live rats and 2 minutes to kill them in,” observed Lewis Carroll in the Monthly Packet in February 1880. “The question is, can this be done?”

Consider the original statement: 6 cats can kill 6 rats in 6 minutes. What can this actually mean? Carroll counts at least four possibilities:

A. “All 6 cats are needed to kill a rat; and this they do in one minute, the other rats standing meekly by, waiting for their turn.”

B. “3 cats are needed to kill a rat, and they do it in 2 minutes.”

C. “2 cats are needed, and they do it in 3 minutes.”

D. “Each cat kills a rat all by itself, and takes 6 minutes to do it.”

Now try to apply these to our conclusion that 12 cats can kill 100 rats in 50 minutes. Cases A and B work out, but Case C can work only if we understand that fractional deaths are possible: that 2 cats could kill two-thirds of a rat in 2 minutes. Similarly, Case D works only if a cat can kill one-third of a rat in 2 minutes.

The only way to resolve this absurdity, it seems, is to supply extra cats. “In case C less than 2 extra cats would be of no use. If 2 were supplied, and if they began killing their 4 rats at the beginning of the time, they would finish them in 12 minutes, and have 36 minutes to spare, during which they might weep, like Alexander, because there were not 12 more rats to kill. In case D, one extra cat would suffice; it would kill its 4 rats in 24 minutes, and have 24 minutes to spare, during which it could have killed another 4. But in neither case could any use be made of the last 2 minutes, except to half-kill rats — a barbarity we need not take into consideration.”

“To sum up our results: If the 6 cats kill the 6 rats by method A or B, the answer is ’12’; if by method C, ’14’; if by method D, ’13’.”

(Another problem: “If a cat can kill a rat in a minute, how long would it be killing 60,000 rats? Ah, how long, indeed! My private opinion is that the rats would kill the cat.”)

In a Word

celsitude

n. height; elevation; altitude

faineant

n. one who does nothing; an idler

ataraxia

n. a pleasure that comes when the mind is at rest

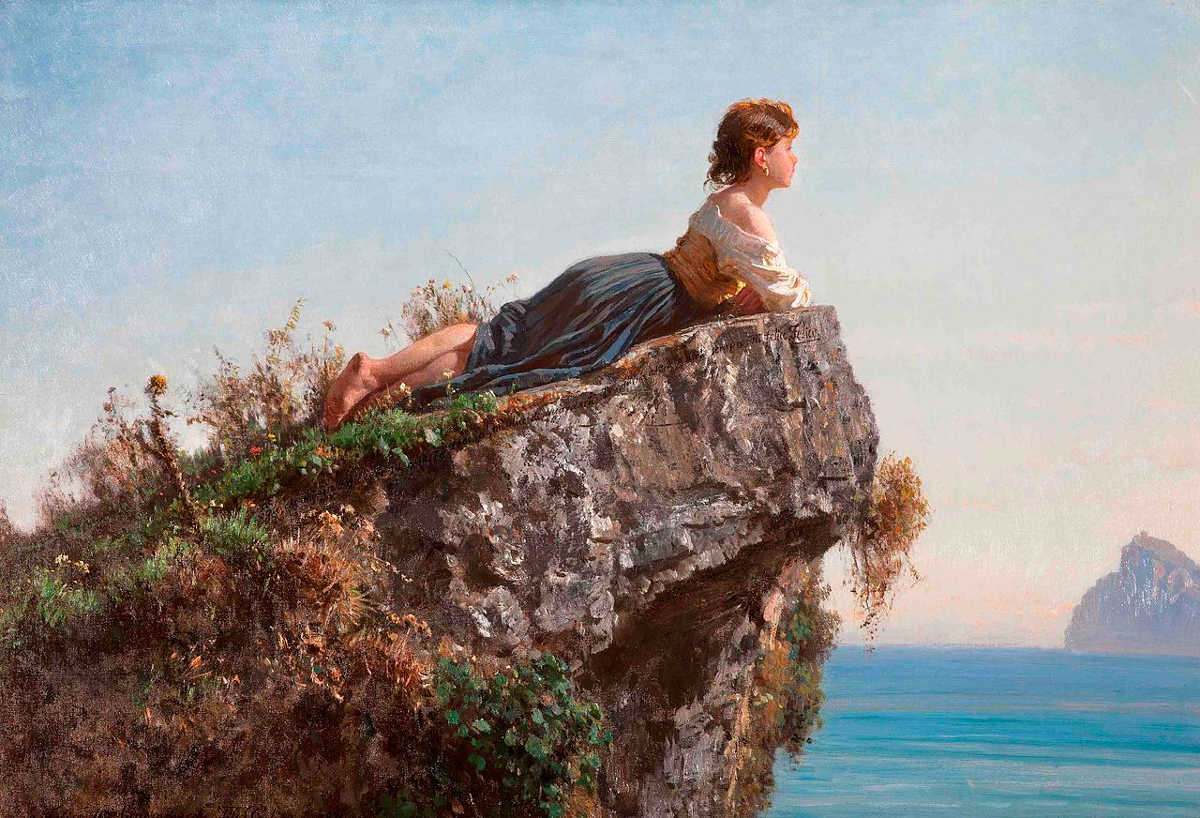

Inspiration

A poor artist is visited by a time traveler from the future. The traveler is an art critic who has seen the artist’s work and is convinced that he’s one of the greatest painters of his time. In looking at the artist’s current paintings, the critic realizes that the artist hasn’t yet reached the zenith of his ability. He gives him some reproductions of his later work and then returns to the future. The artist spends the rest of his life copying these reproductions onto canvas, securing his reputation.

What is the problem here? Kurt Gödel showed in 1949 that time travel might be physically possible, and there’s no contradiction involved in the critic arriving in the artist’s garret, giving him the reproductions, and later admiring the painter’s copies of them — that loop might simply exist in the fabric of time.

What’s missing is the source of the artistic creativity that produces the paintings. “No one doubts the aesthetic value of the artist’s paintings, nor the sense in which the critic’s reproductions reflect this value,” writes philospher Storrs McCall. “What is incomprehensible is: who or what creates the works that future generations value? Where is the artistic creativity to be found? Unlike the traditional ‘paradoxes of time travel’, this problem has no solution.”

(Storrs McCall, “An Insoluble Problem,” Analysis 70:4 [October 2010], 647-648.)

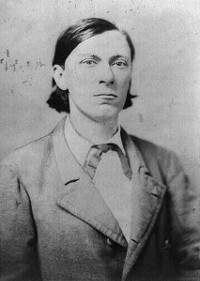

A Point of Duty

Secessionist Roger A. Pryor was visiting Fort Sumter just before the outbreak of the Civil War when he accidentally drank a bottle of poison. A Union doctor named Samuel Crawford pumped his stomach, saving his life.

“Some of us questioned the doctor’s right to interpose in a case of this kind,” wrote Union captain Abner Doubleday. “It was argued that if any rebel leader chose to come over to Fort Sumter and poison himself, the Medical Department had no business to interfere with such a laudable intention.”

“The doctor, however, claimed, with some show of reason, that he himself was held responsible to the United States for the medicine in the hospital, and therefore he could not permit Pryor to carry any of it away.”