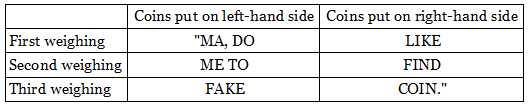

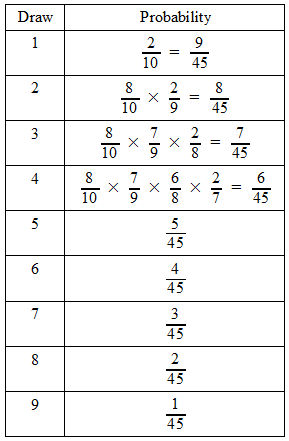

This is from Puzzling Stack Exchange, which gives the following solution (unfortunately the second page of Tolkien’s letter is missing):

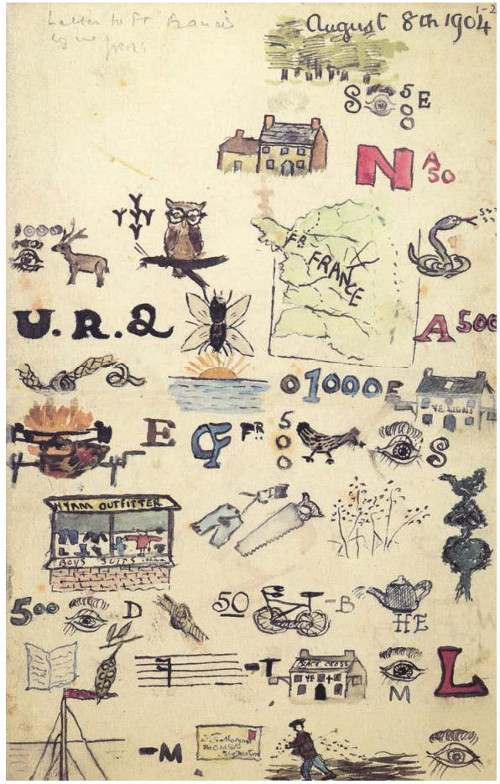

Tolkien’s address, in the upper right, is Woodside House, Rednal (wood, S, eye, 500=D, E, house, red [N, A, 50=L])

The rest of the page reads:

My dear wise owl Fr. Francis, (1000=M, eye, deer, Y’s, owl, “Fr.”, France, hiss)

You are too bad (U, R, 2, bee, A, 500=D)

not to come in (knot, 2, sea, O, 1000=M, E, inn)

spite of Fr. Dennis. (spit, E, “OF:, “Fr.”, 500=D, hen, eye, S)

I am so sorry you (Hyam, sew, saw, rye, yew)

did not like the (500=D, eye, D, knot, 50=L, “bike” – B, tea, HE)

word “piano” in my l… (words, pea, “note” – T, inn, M, eye, 50=L)

…ast letter. So I… (“mast” – M, letter, sow, eye)

As some of the commenters mention, the “word piano” interpretation seems uncertain, but it’s hard to know what was intended given so little context. Any ideas?

UPDATE: Many readers point out that the “note” is a rest, which suggests that the word may be something like letterpress (letter, pea, rest – t) or padres (pod, rest – t), the latter of which might indeed have drawn an objection from Father Morgan. This may be the rest of the letter. (Thanks, Bruce.)