concentus

n. a harmonious combination, especially of sounds

catachthonian

adj. subterranean

Reverberating harmonies in Ambleside Cave, Cumbria:

concentus

n. a harmonious combination, especially of sounds

catachthonian

adj. subterranean

Reverberating harmonies in Ambleside Cave, Cumbria:

A replacement for the Turing test has been proposed. The original test, in which a computer program tries to fool a human judge into thinking it’s human during a five-minute text-only conversation, has been criticized because the central task of devising a false identity is not part of intelligence, and because some conversations may require relatively little intelligent reasoning.

The new test would be based on so-called Winograd schemas, devised by Stanford computer scientist Terry Winograd in 1972. Here’s the classic example:

The city councilmen refused the demonstrators a permit because they [feared/advocated] violence.

If the word feared is used, to whom does they refer, the councilmen or the demonstrators? What if we change feared to advocated? You know the answers to these questions because you have a practical understanding of anxious councilmen. Computers find the task more difficult because it requires not only natural language processing and commonsense reasoning but a working knowledge of the real world.

“Our WS [Winograd schemas] challenge does not allow a subject to hide behind a smokescreen of verbal tricks, playfulness, or canned responses,” wrote University of Toronto computer scientist Hector Levesque in proposing the contest in 2014. “Assuming a subject is willing to take a WS test at all, much will be learned quite unambiguously about the subject in a few minutes.”

In July 2014 Nuance Communications announced that it will sponsor an annual Winograd Schema Challenge, with a prize of $25,000 for the computer that best matches human performance. The first competition will be held at the 2016 International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, July 9-15 in New York City.

Here’s another possibility: Two Dartmouth professors have proposed a Turing Test in Creative Arts, in which “we ask if machines are capable of generating sonnets, short stories, or dance music that is indistinguishable from human-generated works, though perhaps not yet so advanced as Shakespeare, O. Henry or Daft Punk.” The results of that competition will be announced May 18 at Dartmouth’s Digital Arts Exposition.

(Thanks, Kristján and Sharon.)

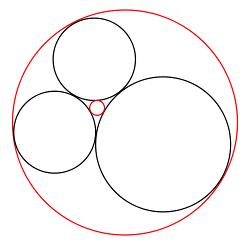

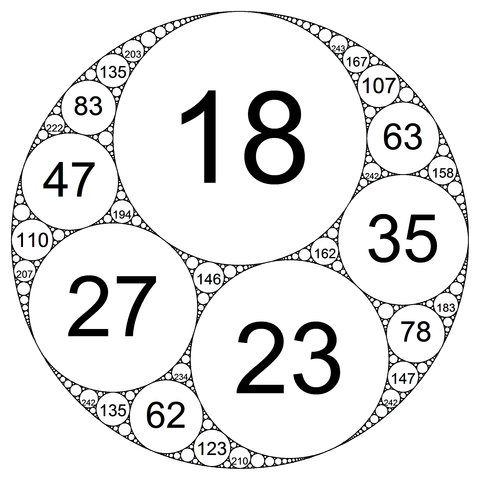

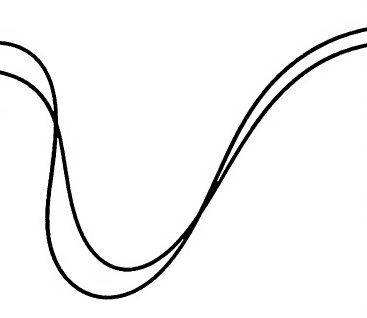

In 2014 I described Descartes’ theorem, which shows how to find a fourth circle that’s tangent to three “kissing circles.”

Descartes’ equation refers to the “curvature” of each circle: this is just the reciprocal of the radius, so a circle with radius 1/3 would have a curvature of 3. (This makes sense intuitively — a circle with a small radius “curves more” than a larger one.)

Remarkably, if the four starting circles all have integer curvature, then so will every circle we pack into the figure, each kissing the three around it. In the limit the figure becomes a fractal containing an infinite number of circles. It’s called an Apollonian gasket.

07/29/2016 UPDATE: By coincidence, the U.S. quarter, nickel, and dime make three of the four generating circles in an integral packing — see the caption accompanying the first figure on this page. (Thanks, Trevor.)

Is immortality really so attractive? Even the most pleasant activities would begin to pall with repetition, so the only way to avoid an endlessly boring existence would be to undergo continual changes in personality, taking on different interests and values from those we have today. But such a person would be very different from our present self — so different, argues Cambridge philosopher Bernard Williams, that we could not judge her life to be good from our own present point of view. We would have no reason to hope to become that person. Thus immortality must be either endlessly boring or an existence with which we cannot identify. On balance, then, it’s worse than the mortal existence we know.

“Immortality, or a state without death, would be meaningless,” writes Williams, “so, in a sense, death gives the meaning to life.”

(Bernard Williams, “The Makropulos Case,” in Problems of the Self, 1973.)

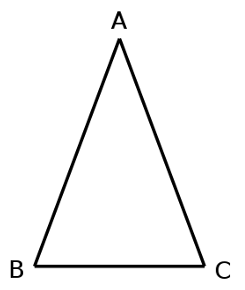

Here’s an isosceles triangle. Sides AB and AC are equal, and this means that the angles opposite those sides are equal as well.

That’s intuitively reasonable, but proving it is tricky. Teachers of Euclid’s Elements came to call it the pons asinorum, or bridge of donkeys, because it was the first challenge that separated quick students from slow.

The simplest proof, attributed to Pappus of Alexandria, requires no additional construction at all. We know that two triangles are congruent if two sides and the included angle of one triangle are congruent to their corresponding parts in the other (the “side-angle-side” postulate). So Pappus suggested simply picking up the triangle above, flipping it over, and putting it down again, to produce a second triangle ACB. Now if we compare the respective parts of the two triangles, we find that angle A is equal to itself, AB = AC, and AC = AB. Thus the “left-hand” angles of the two triangles are congruent, and it follows that the base angles of the original triangle above are equal.

In his 1879 book Euclid and his Modern Rivals, Lewis Carroll accepts the proof but remarks that it “reminds one a little too vividly of the man who walked down his own throat.”

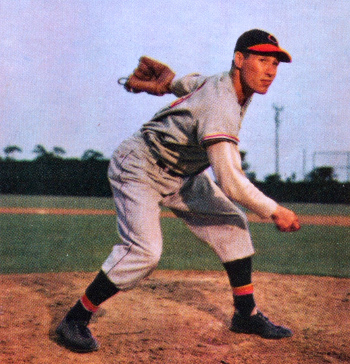

On Mother’s Day, May 14, 1939, Cleveland Indians pitcher Bob Feller took his mother to Comiskey Park to see him pitch against the Chicago White Sox. Lena Feller, who had traveled 250 miles from Van Meter, Iowa, with her husband and daughter, sat in the grandstand between home and first base and watch her son amass a 6-0 lead in the first three innings.

Then, in the bottom of the third, Chicago third baseman Marvin Owen hit a line drive into her face.

Feller was following through with his pitching motion and saw it happen. “I felt sick,” he wrote later, “but I saw that Mother was conscious. … I saw the police and ushers leading her out and I had to put down the impulse to run to the stands. Instead, I kept on pitching. I felt giddy and I became wild and couldn’t seem to find the plate. I know the Sox scored three runs, but I’m not sure how.”

The injury was painful but not serious. Feller managed to win the game (9-4) and then hurried to the hospital. In his 1947 autobiography, Strikeout Story, he wrote, “Mother looked up from the hospital bed, her face bruised and both eyes blacked, and she was still able to smile reassuringly. ‘My head aches, Robert,’ she said, ‘but I’m all right. Now don’t go blaming yourself … it wasn’t your fault.'”

My lousy car has an odometer without 4s — in every position, the counter advances from 3 directly to 5. For example, when it read 000039 I drove one mile and watched it roll over to 000050. Today the odometer reads 002005. How many miles has the car actually traveled?

Bombers in World War I were typically manned by two crew members, a pilot and an observer. The pilot operated the forward machine gun and the observer the rear one, so they depended on one another for their survival. In addition, the two men would share the same hut or tent, eat their meals together, and often spend all their free time together. This closeness produced “some remarkable and amusing results,” writes Hubert Griffith in R.A.F. Occasions (1941):

There were pilots who took the precaution of teaching their observers to fly, with the primitive dual-control fitted to the R.E.8 of those days — and at least one couple who used to take over the controls almost indiscriminately from one another: there was the story that went round the mess, of Creaghan (the pilot) arriving down out of the air one day and accusing his observer of having made a bad landing, and of Vigers, the observer, in turn accusing Creaghan of having made a bad landing. It turned out on investigation that each of them had thought the other to be in control of the aircraft; that because of this neither of them, in fact, had been in control at all; and that, in the absence of any guiding authority, the machine had made a quite fairly creditable landing on her own.

Griffith writes, “It was, I suppose, the most personal relationship that ever existed.”

You come upon the track of a bicycle in the mud. Was the bicycle traveling to the left or the right?

A British officer in the 44th regiment, who had occasion, when in Paris, to pass one of the bridges across the Seine, had his boots, which had been previously well polished, dirtied by a poodle Dog rubbing against them. He in consequence went to a man who was stationed on the bridge, and had them cleaned. The same circumstance having occurred more than once, his curiosity was excited, and he watched the Dog. He saw him roll himself in the mud of the river, and then watch for a person with well polished boots, against which he contrived to rub himself. Finding that the shoeblack was the owner of the Dog, he taxed him with the artifice; and, after a little hesitation, he confessed that he had taught the Dog the trick in order to procure customers for himself. The officer being much struck with the Dog’s sagacity, purchased him at a high price, and brought him to England. He kept him tied up in London for some time, and then released him. The dog remained with him a day or two, and then made his escape. A fortnight afterwards he was found with his former master, pursuing his old trade on the bridge.

— Samuel Griswold Goodrich, Tales of Animals, 1835