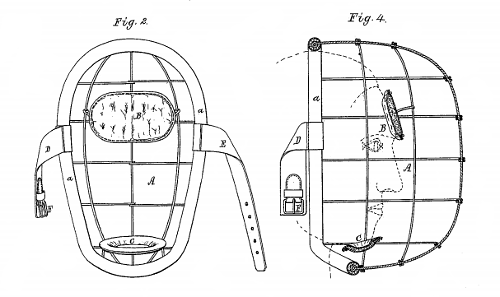

In the 1870s baseball catchers played bare-faced, routinely suffering broken noses and teeth; to protect themselves they stood two dozen feet behind the batter, which prevented the pitcher from throwing his best pitches. Finally Fred Winthrop Thayer, captain of Harvard’s team, invented a “Safety-Mask for Base-Ball Players” to minimize the damage.

“It is not an unfrequent occurrence in the game of base-ball for a player to be severely injured in the face by a ball thrown against it,” he wrote in the patent application. “With my face-guard such an accident cannot happen.”

When catcher Jim Tyng first wore Thayer’s mask on April 12, 1877, it was roundly derided. Spectators yelled “Mad dog!” and “Muzzle ’em!”, and opposing players greeted Tyng with “good natured though somewhat derisive pity.” The Portland, Maine, Sunday Telegram wrote, “There is a great deal of beastly humbug in contrivances to protect men from things which do not happen. There is about as much sense in putting a lightning rod on a catcher as there is a mask.”

Catchers finally submitted when sportwriter Henry Chadwick faulted their “moral courage.” “Plucky enough to face the dangerous fire of balls from the swift pitcher,” he wrote, “they tremble before the remarks of the small boys of the crowd of spectators, and prefer to run the risk of broken cheek bones, dislocated jaws, a smashed nose or blackened eyes, than stand the chaff of the fools in the assemblage.”

Today Thayer’s Harvard mask is in the National Baseball Hall of Fame.