“Ingliz menuyu” presented to writer William Dalrymple at a family restaurant in Turkey in 1986:

SOAP

Ayas soap

Turkish tripte soap

Sheeps foot

Macaront

Water pies

EATS FROM MEAT

Deuner kepab with pi

Kebap with green pe

Kebap in paper

Meat pide

Kebap with mas patato

Samall bits of meat grilled

Almb chops

VEGETABLES

Meat in earthenware stev pot

Stfue goreen pepper

Stuffed squash

Stuffed tomatoes z

Stuffed cabbages lea

Leek with finced meat

Clery

SALAD

Brain salad

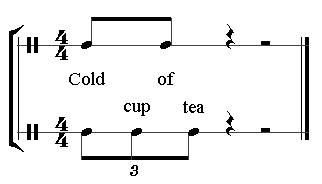

Cacik — a drink made ay ay

And cucumber

FRYING PANS

Fried aggs

Scram fried aggs

Scrum fried omlat

Omlat with brain

SWEETS AND RFUITS

Stewed atrawberry

Nightingales nests

Virgin lips

A sweet dish of thinsh of batter with butter

Banane

Meon

Leeches

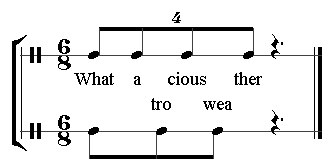

“It was a difficult choice,” he writes. From In Xanadu, 1989.