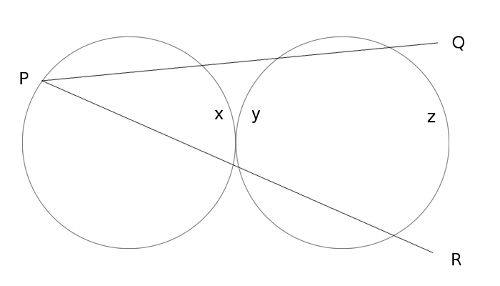

If two unit circles are tangent externally as shown, and from a point P on one circle rays PQ and PR are drawn intersecting both circles, then arc lengths x + y = z.

From Claudi Alsina and Roger B. Nelsen, Icons of Mathematics, 2011.

If two unit circles are tangent externally as shown, and from a point P on one circle rays PQ and PR are drawn intersecting both circles, then arc lengths x + y = z.

From Claudi Alsina and Roger B. Nelsen, Icons of Mathematics, 2011.

In a special football game, a team scores 7 points for a touchdown and 3 points for a field goal. What’s the largest mathematically unreachable number of points that a team can score (in an infinitely long game)?

More maxims of François VI, Duc de La Rochefoucauld (1613–1680):

And “‘Tis a Mistake to imagine that only the violent Passions, such as Ambition and Love, can triumph over the rest. Laziness, languid as it is, often masters them all; she indeed influences all our Designs and Actions, and insensibly consumes and destroys both the Passions and the Virtues.”

A problem by Atlantic College mathematician Paul Belcher:

Anna and Bert invite n other couples to a dinner party. Before the meal begins, some people shake hands. No one shakes hands with their own partner, no one shakes hands with themselves, and no two people shake hands with each other more than once. Afterward, Anna asks all the other 2n + 1 people how many times they shook hands, and she gets a different answer from each of them. How many times did Anna shake hands?

topolatry

n. excessive reverence for a place

Of the million or so Japanese who visit Paris each year, about 12 have to be repatriated due to “Paris syndrome,” a transient psychological disorder brought on when the mundane reality of the city clashes with their romanticized expectations.

The syndrome was first diagnosed by Hiroaki Ota, a Japanese psychiatrist working in France. Symptoms include delusional states, hallucinations, feelings of persecution, and anxiety.

“Fragile travellers can lose their bearings,” psychologist Hervé Benhamou told Le Journal du Dimanche. “When the idea they have of the country meets the reality of what they discover, it can provoke a crisis.”

(A. Viala et al., “Les japonais en voyage pathologique à Paris : un modèle original de prise en charge transculturelle,” Nervure 5 (2004): 31–34.)

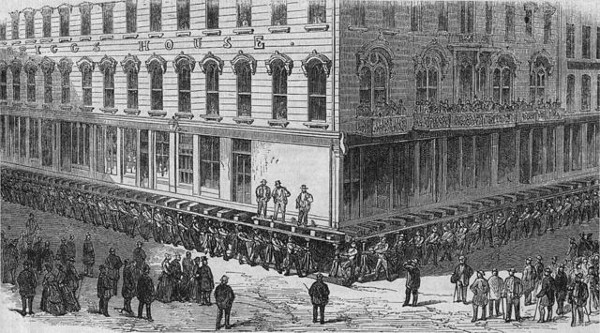

In 1868, visiting Scotsman David Macrae was astonished to see Chicago transforming itself — dozens of buildings were transplanted to the suburbs, and hotels weighing hundreds of tons were raised on jackscrews. In this week’s episode of the Futility Closet podcast we’ll follow the city’s astounding 20-year effort to rid itself of sewage and disease.

We’ll also learn how a bear almost started World War III and puzzle over the importance of a ringing phone.

In 1946, when Japanese prime minister Hideki Tojo was being held prisoner by the victorious Allies, he asked for a set of dentures so that he could speak clearly during his war crimes trial.

The dentures were made by 22-year-old military dentist E.J. Mallory. “I figured it was my duty to carry out the assignment,” Mallory remembered in 1988. “But that didn’t mean I couldn’t have fun with it.”

An amateur ham radio operator, he inscribed the phrase “Remember Pearl Harbor” in Morse code into the dentures and delivered them to Tojo.

Mallory and his colleague George Foster told a few friends, but the secret got out and the two had to awaken Tojo in the middle of the night to borrow back the dentures and grind out the message. The next day, when a colonel confronted them, they were able to say truthfully that there was no message.

It’s not known whether Tojo ever found out what had happened. He was executed in 1948.

“It wasn’t anything done in anger,” Mallory remembered in 1995. “It’s just that not many people had the chance to get those words into his mouth.”

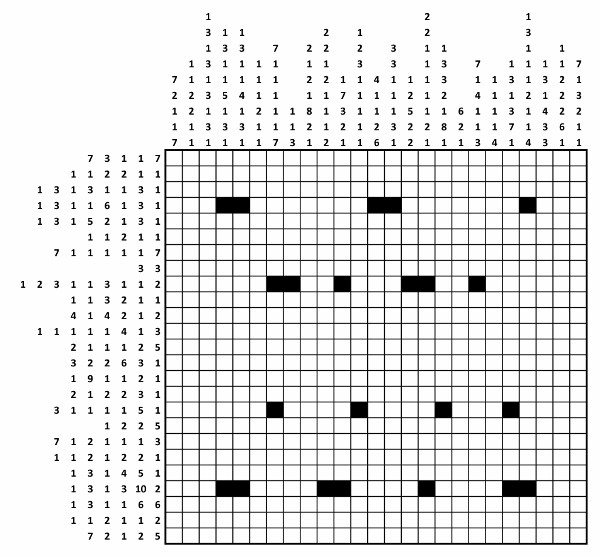

Here’s a unique challenge for the holidays — one of the United Kingdom’s intelligence agencies, GCHQ, is distributing the puzzle above on its Christmas card this year. (See GCHQ’s website for details and a high-resolution grid.)

The puzzle is a nonogram: Each row and column bears a string of numbers that indicates the lengths of consecutive runs of black squares that will appear there when the grid has been completed. For example, “3 3” in the eighth row means that in the finished puzzle two shaded sections of 3 squares each will appear somewhere along its length. Some squares in the grid have already been shaded to get you started.

“By solving this first puzzle players will create an image that leads to a series of increasingly complex challenges,” notes the agency. “Once all stages have been unlocked and completed successfully, players are invited to submit their answer via a given GCHQ email address by 31 January 2016. The winner will then be drawn from all the successful entries and notified soon after.” The agency invites players to make a donation to the U.K.’s National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children if they’ve enjoyed the puzzle.

(Thanks, Alex.)

02/08/2016 UPDATE: The answers have now been revealed — see the link at the bottom of this post.

A reader passed this along — in a lecture at the University of Maryland (starting around 34:18), Douglas Hofstadter presents Napoleon’s theorem by means of a sonnet:

Equilateral triangles three we’ll erect

Facing out on the sides of our friend ABC.

We’ll link up their centers, and when we inspect

These segments, we find tripartite symmetry.

Equilateral triangles three we’ll next draw

Facing in on the sides of our friend BCA.

Their centers we’ll link up, and what we just saw

Will enchant us again, in its own smaller way.

Napoleon triangles two we’ve now found.

Their centers seem close, and indeed that’s the case:

They occupy one and the same centroid place!

Our triangle pair forms a figure and ground,

Defining a six-edgéd torus, we see,

Whose area’s the same as our friend, CAB!

(Thanks, Evan.)