ploration

n. weeping

begrutten

adj. having a face swollen from weeping

Niobe

n. an inconsolably bereaved woman, a weeping woman

ploration

n. weeping

begrutten

adj. having a face swollen from weeping

Niobe

n. an inconsolably bereaved woman, a weeping woman

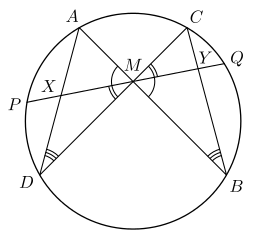

Draw a circle, choose any chord PQ, and draw two further chords AB and CD through its midpoint M. Now, if AD and BC intersect PQ at X and Y, M will always be the midpoint of XY.

In Icons of Mathematics (2011), Claudi Alsina and Roger Nelsen write, “The surprise is the unexpected symmetry arising from an almost random construction.” The theorem first appeared in 1815.

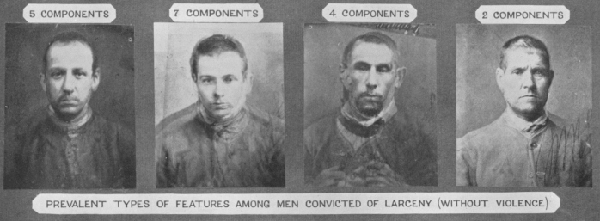

In 1883 Francis Galton tried an experiment: He combined multiple photographs of criminals into composite images, hoping to discover an underlying “type.” He didn’t get a strong result, but he did notice something odd about the composite faces: They tended to be more attractive than the individual images that made them up. He found similar effects with other groups — a composite “sick person” seemed healthier than its constituent images, and a group of good-looking people became even more beautiful in composite. In one case he made a “singularly beautiful combination of the faces of six different Roman ladies, forming a charming ideal profile.”

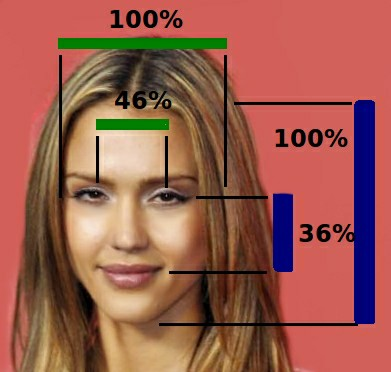

The lesson seems to be that we find an “average” face most attractive — a face is appealing not because it has unusual features but because it lacks them. For example (below), a University of Toronto study found that the shape of Jessica Alba’s face approaches the average for all female profiles: The distance between her pupils is 46 percent of the width of her face, and the distance between her eyes and her mouth is 36 percent of the length of her face. The fact that we find this attractive makes some evolutionary sense: Natural selection tends to drive out disadvantageous features, so a partner with an “average” face is more likely to be healthy and fertile.

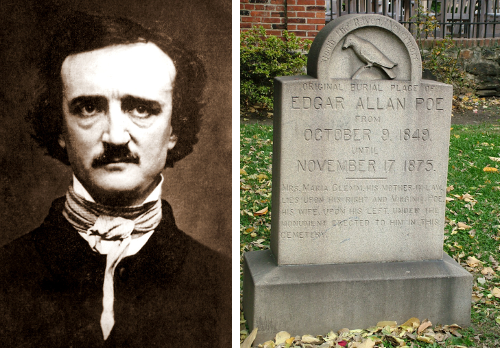

For most of the 20th century, a man in black appeared each year at the grave of Edgar Allan Poe. In the predawn hours of January 19, he would drink a toast with French cognac and leave behind three roses in a distinctive arrangement. No one knows who he was or why he did this. In this episode of the Futility Closet podcast we review the history of the “Poe Toaster” and his long association with the great poet’s memorial.

We’ll also consider whether Winnie-the-Pooh should be placed on Ritalin and puzzle over why a man would shoot an unoffending monk.

In A Thing or Two About Music (1972), Nicolas Slonimsky describes a series of “puzzle minuets” composed by 18th-century harpsichordist Johann Schobert:

Schobert is not a misprint for Schubert. He was an estimable Silesian-born musician who settled in Paris in 1760 and wrote many compositions in the elegant style of the time. Mozart knew his music well and was even influenced by his easy grace in writing piano pieces. Schobert was something of a musical scientist. Among his compositions is a page entitled, ‘A Curious Musical Piece Which Can Be Played on the Piano, on the Violin, and on the Bass, and at that in Different Ways.’ This page contained five minuets, one of which could be played upside down without any change, one which would result in a new piece when turned upside down, and one which would furnish a continuation upside down. Two could be played on the violin and on the bass by assigning the treble clef right side up and the bass clef upside down.

The full page is here. I haven’t tried playing it.

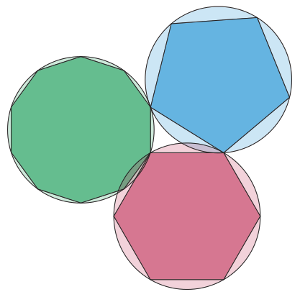

Draw three circles of equal size and inscribe them with a pentagon, a hexagon, and a decagon.

The sides of these figures form a right triangle — and half of a golden rectangle.

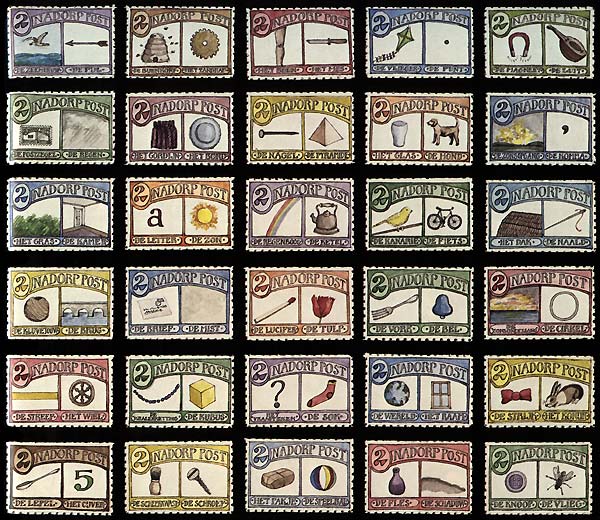

Artist Donald Evans spent his life painting the postage stamps of nonexistent countries. “The stamps are a kind of diary or journal,” he said. “It’s vicarious traveling for me to a made-up world that I like better than the one that I’m in.”

“On little paper rectangles he painted precise transcriptions of his life,” wrote Willy Eisenhart in The World of Donald Evans (1980). “He commemorated everything that was special to him, disguised in a code of stamps from his own imaginary countries — each detailed with its own history, geography, climate, currency and customs — all of it representative of the real world but, like real stamps, apart from it in calm tranquility.”

He painted them as watercolors the size of actual stamps, handling the paper with tweezers and working always with the same trusty brush. When they were finished he would sometimes cancel them with a fanciful postmark carved from a rubber eraser. He preserved them in a 330-page book modeled on a real stamp catalogue, recording in each case the name of the fictional country, the fictional date, the subject and occasion of the stamp’s issue, and the date on which he had completed the painting. He called this book his Catalogue of the World.

By the time he died in an Amsterdam fire in 1977, Evans had painted nearly 4,000 stamps from 42 imaginary nations, bearing dates from 1852 to 1973. He told the Paris Review, “The more I do, the more crazy and minuscule the detail becomes and the more stamplike they become. And that intrigues me. … One of the things I get excited about in making this work is that I try to make it look real.”

The guiding principle for his work, he said, was “basically that it describes something which I think is interesting and that it looks like a stamp.”

We cannot seek or attain health, wealth, learning, justice or kindness in general. Action is always specific, concrete, individualized, unique. And consequently judgments as to acts to be performed must be similarly specific. … A man who aims at health as a distinct end becomes a valetudinarian, or a fanatic, or a mechanical performer of exercises, or an athlete so one-sided that his pursuit of bodily development injures his heart. When the endeavor to realize a so-called end does not temper and color all other activities, life is portioned out into strips and fractions. Certain acts and times are devoted to getting health, others to cultivating religion, others to seeking learning, to being a good citizen, a devotee of fine art and so on. This is the only logical alternative to subordinating all aims to the accomplishment of one alone — fanaticism. This is out of fashion at present, but who can say how much of distraction and dissipation in life, and how much of its hard and narrow rigidity is the outcome of men’s failure to realize that each situation has its own unique end and that the whole personality should be concerned with it?

— John Dewey, Reconstruction in Philosophy, 1920

A.B. Kempe’s provocatively titled How to Draw a Straight Line (1877) addresses a fundamental question. In the Elements, Euclid derives his results by drawing straight lines and circles. We can draw a circle by rotating a rigid body (such as a pair of compasses) around a fixed point. But how can we produce a straight line? “If we are to draw a straight line with a ruler, the ruler must itself have a straight edge; and how are we going to make the edge straight? We come back to our starting-point.”

Kempe’s solution is the Peaucellier–Lipkin linkage, an ingenious mechanism that was invented in 1864 by the French army engineer Charles-Nicolas Peaucellier, forgotten, and rediscovered by a Russian student named Yom Tov Lipman Lipkin. In the figure shown here, the colors denote bars of equal length. The green and red bars form a linkage called a Peaucellier cell, and adding the blue links causes the red rhombus to flex as it moves. A pencil fixed at the outer vertex of the rhombus will draw a straight line.

James Sylvester introduced Peaucellier’s discovery to England in a lecture at the Royal Institution in January 1874, which Kempe says “excited very great interest and was the commencement of the consideration of the subject of linkages in this country.” Sylvester writes that when he showed a model of the linkage to Lord Kelvin, he “nursed it as if it had been his own child, and when a motion was made to relieve him of it, replied ‘No! I have not had nearly enough of it — it is the most beautiful thing I have ever seen in my life.'”

“It is true that that may hold in these things, which is the general root of superstition; namely, that men observe when things hit, and not when they miss; and commit to memory the one, and forget and pass over the other.” — Francis Bacon