Have Gun

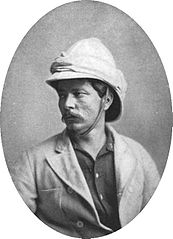

Welshman Henry Morton Stanley — famous for seeking explorer David Livingstone in Africa — fought on both sides in the American Civil War.

In April 1862, when just 21 years old, he fought in the Confederate Army’s 6th Arkansas infantry regiment at the Battle of Shiloh. Captured, he swore allegiance to the United States and joined the Union Army in June. He was discharged after two weeks’ service due to severe illness, but recovered and went on to join the U.S. Navy in 1864.

In The Galvanized Yankees, Dee Brown writes, Stanley “probably became the only man ever to serve in the Confederate Army, the Union Army, and the Union Navy.”

Reckoning

Two mathematicians were having dinner. One was complaining: ‘The average person is a mathematical idiot. People cannot do arithmetic correctly, cannot balance a checkbook, cannot calculate a tip, cannot do percents, …’ The other mathematician disagreed: ‘You’re exaggerating. People know all the math they need to know.’

Later in the dinner the complainer went to the men’s room. The other mathematician beckoned the waitress to his table and said, ‘The next time you come past our table, I am going to stop you and ask you a question. No matter what I say, I want you to answer by saying “x squared.”‘ She agreed. When the other mathematician returned, his companion said, ‘I’m tired of your complaining. I’m going to stop the next person who passes our table and ask him or her an elementary calculus question, and I bet the person can solve it.’ Soon the waitress came by and he asked: ‘Excuse me, Miss, but can you tell me what the integral of 2x with respect to x is?’ The waitress replied: ‘x squared.’ The mathematician said, ‘See!’ His friend said, ‘Oh … I guess you were right.’ And the waitress said, ‘Plus a constant.’

— Michael Stueben, Twenty Years Before the Blackboard, 1998

Piggyback

Between Grana and Casorzo, Italy, grows a cherry tree atop a mulberry tree.

It’s not uncommon for a small tree to grow on a larger one, but it’s rare for them to reach such a large size. The cherry even flowers in the spring.

The pair are known as the Bialbero de Casorzo, or “double tree of Casorzo.”

In a Word

cogitabund

adj. musing, meditating, thoughtful, deep in thought

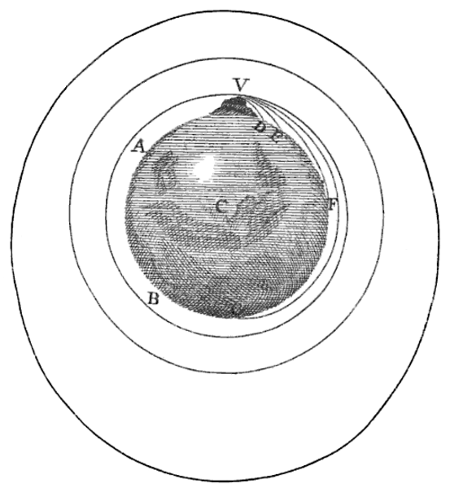

In his Treatise of the System of the World, Isaac Newton imagines firing cannonballs with greater and greater velocity from a high mountaintop. “The body projected with a less velocity, describes the lesser arc VD, and with a greater velocity, the greater arc VE, and augmenting the velocity, it goes farther and farther to F and G; if the velocity was still more and more augmented, it would reach at last quite beyond the circumference of the Earth, and return to the mountain from which it was projected.”

Indeed, if air resistance is not a factor, the cannonball will return to the mountain with the same velocity with which it left it, “and retaining the same velocity, it will describe the same curve over and over, by the same law,” like the moon. Thus with a simple thought experiment Newton conceived that gravity was the key force underlying planetary motion.

In a fitting tribute, the diagram above is now traveling beyond the solar system on the Voyager Golden Record, on a journey that its author helped to make possible.

Comment

Whoever prepared the index for Desmond Ryan’s 1967 book The Fenian Chief: A Biography of James Stephens had a mordant sense of humor — it contains this entry:

O'Brien, An: never turns his back on an enemy, 32 would never retreat from fields in which ancestors were kings, 33 does, 34

Roaring Blazes

For his 1991 film Backdraft, director Ron Howard wanted fire to have a “brain,” like the shark in Jaws. So sound designer Gary Rydstrom added animal growls and howls to the sound of the flames. “You don’t hear them as animal sounds, but subconsciously it gives it an intelligence or a complexity it wouldn’t normally have.”

“For the suck in of air we used coyote howls. It wasn’t just a simple wind — it was more intelligent.”

“A lot of the fireball explosions were sweetened with monkey screams and different animal growls. Cougars make a great fire explosion sweetener. There’s a complexity to natural sounds, especially animal sounds, that is really wonderful.”

(From Vincent LoBrutto, Sound-on-Film, 1994.)

A Many-Sided Story

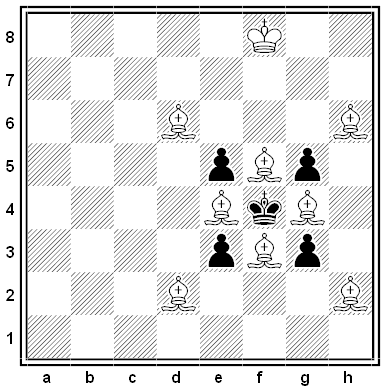

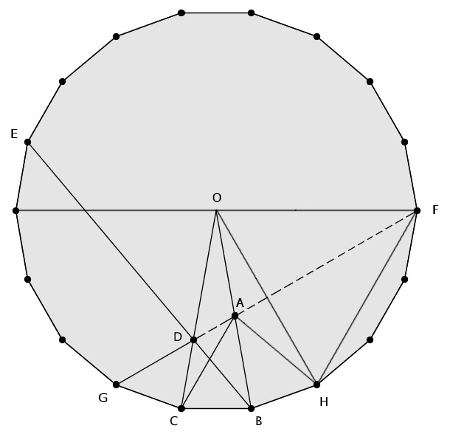

Back in September I posted a geometry problem mentioned by Andy Liu in Math Horizons in November 1997. Several readers recognized it and wrote in with the pretty solution — here it is:

As before, we’re given that ∠DCA = 20°, ∠ACB = 60°, ∠CBD = 50°, and ∠DBA = 30°, and we’re asked to find ∠CAD. Start by extending CD and BA to intersect at O, and draw a circle with O as the center and OB as the radius. Now, because ∠OCB and ∠OBC both measure 80°, BC is one side of an 18-gon inscribed in this circle.

Let E be the fifth vertex of this 18-gon to the left of C and F be the fifth vertex to the right of C. Also let G be the first vertex to the left of C and H be the first vertex to the right of B. Then, by symmetry, EB, GF, and OC meet. And by the central angle theorem ∠EBC is half the measure of ∠EOC, or 50°, so EB, GF, and OC meet at D.

Now, OFH is an equilateral triangle (by symmetry and the fact that ∠FOH is 60°), and ∠GFH is half the measure of ∠GOH, or 30° (again by the central angle theorem). So GF bisects OH.

Finally, by symmetry, AC = AH. But ∠ACD = 20° = ∠AOD, so triangle AOC is equilateral and AC = AO. Then AO = AH, and by symmetry AF bisects OH. And that means that GF passes through A.

Therefore, ∠BAD = ∠OAF, which is half of ∠OAH, or 70°. And from the information given at the start we can infer that ∠CAB = 40°. So ∠CAD = 30°.

I’m told that there are more problems like this in I.F. Sharygin’s 1988 book Problems in Plane Geometry. Thanks to the folks who wrote in about this.

11/06/2015 UPDATE: Another reader pointed out an alternate solution, discovered by Edward Mann Langley in 1922. (Thanks, January.)

“The Man in the Moon”

Phil Rizzuto’s digressive speaking style earned him a faithful following during his 40-year career as announcer for the New York Yankees. In 1993, Tom Peyer and Hart Seely found that the announcer’s disjointed speech worked exceptionally well as found poetry, and they edited a collection titled O Holy Cow! The Selected Verse of Phil Rizzuto. Here’s a sample: the announcer’s thoughts on the death of Yankees catcher Thurman Munson in an airplane crash:

The Yankees have had a traumatic four days.

Actually five days.

That terrible crash with Thurman Munson.

To go through all that agony,

And then today,

You and I along with the rest of the team

Flew to Canton for the services,

And the family …

Very upset.

You know, it might,

It might sound a little corny.

But we have the most beautiful full moon tonight.

And the crowd,

Enjoying whatever is going on right now.

They say it might sound corny,

But to me it’s like some kind of a,

Like an omen.

Both the moon and Thurman Munson,

Both ascending up into heaven.

I just can’t get it out of my mind.

I just saw the full moon,

And it just reminded me of Thurman Munson,

And that’s it.

Oops

In 1726, the Swiss naturalist Johann Jakob Scheuchzer mistook the skull and vertebral column of a large salamander from the Miocene epoch for the “betrübten Beingerüst eines alten Sünders” (sad bony remains of an old human sinner) and dubbed it Homo diluvii testis, “the man who witnessed the Deluge.” The fossil lacked a tail or hind legs, so he thought it was the remains of a trampled human child:

It is certain that this [rock] contains the half, or nearly so, of the skeleton of a man; that the substance even of the bones, and, what is more, of the flesh and of parts still softer than the flesh, are there incorporated in the stone; in a word it is one of the rarest relics which we have of that accursed race which was buried under the waters. The figure shows us the contour of the frontal bone, the orbits with the openings which give passage to the great nerves of the fifth pair. We see there the remains of the brain, of the sphenoidal bone, of the roots of the nose, a notable fragment of the maxillary bone, and some vestiges of the liver.

The fossil made its way to Teylers Museum in the Netherlands, where in 1811 Georges Cuvier recognized it as a giant salamander. Ironically, Scheuchzer’s original belief is reflected in the fossil’s modern name, Andrias scheuchzeri — Andrias means “image of man.”