Belgian painter Antoine Wiertz unveiled a gruesome triptych in 1853: Thoughts and Visions of a Severed Head depicts a guillotined head’s impressions of its final three minutes of awareness.

Wietz added a verbal description of each of the panels. Here’s an excerpt from the second minute, “Under the Scaffold”:

For the first time the executed prisoner is conscious of his position.

He measures with his fiery eyes the distance that separates his head from his body and tells himself, ‘My head really is cut off.’

Now the frenzy redoubles in force and energy.

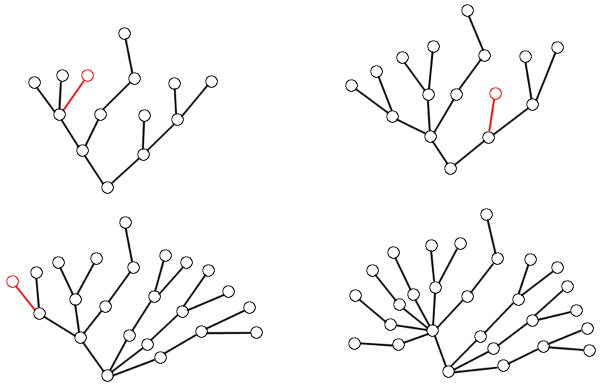

The executed prisoner imagines that his head is burning and turning on itself, that the universe is collapsing and turning with it, that a phosphorescent fluid is whirling around his skull as it melts down.

In this midst of this horrible fever, a mad, incredible, unheard of idea takes possession of the dying brain.

Would you believe it? This man whose head has been chopped off still conceives of a hope. All the blood that remains bubbles, gushes, and courses with fury through all the canals of life to grasp at this hope.

At this moment the executed prisoner is convinced that he is stretching out his convulsive and rage-filled hands toward his expiring head.

I don’t know what this imaginary movement means. Wait … I understand … It’s horrible!

Oh! My God, what is life that it continues the struggle to the very last drop of blood?

In the same year, American author Theodore Witmer had recorded his own impressions of seeing an execution in the 1840s. “Why don’t somebody give us ‘The Reflections of a Decapitated Man?'” he asked. “If it turned out stupid, he might excuse himself for want of a head.”