thersitical

adj. abusive, foul-mouthed, reviling

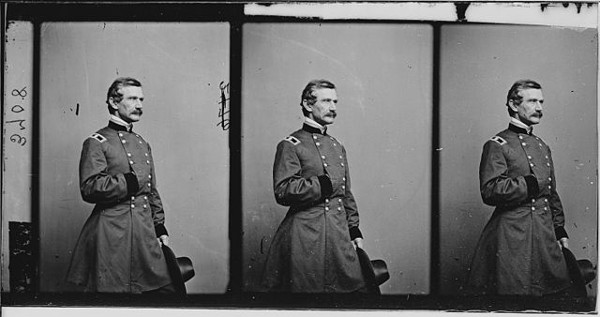

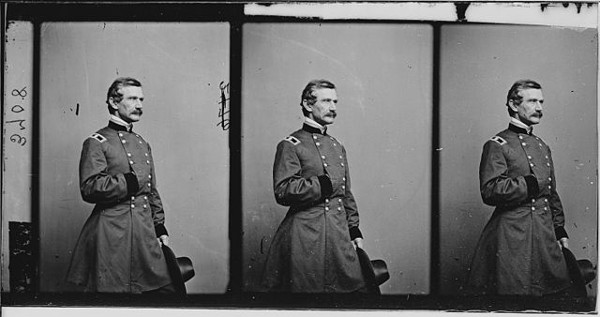

In his Recollections of the Civil War, Charles Anderson Dana called Union general Andrew Atkinson Humphreys “one of the loudest swearers that I ever knew.” “The men of distinguished and brilliant profanity in the war were General Sherman and General Humphreys — I could not mention any others that could be classed with them. General Logan also was a strong swearer, but he was not a West Pointer: he was a civilian. Sherman and Humphreys would swear to make everything blue when some dispatch had not been delivered correctly or they were provoked.”

In Rex v. Sparling (1722), a leather dresser named James Sparling was alleged in the course of 10 days to “profanely swear fifty-four oaths, and profanely curse one hundred and sixty curses, contra formam statuti.” His conviction was overturned because the charge sheet had failed to list them. “For what is a profane oath or curse is a matter of law, and ought not to be left to the judgment of the witness … it is a matter of great dispute among the learned, what are oaths and what curses.”

When in 1985 a man named Callahan called a California highway patrolman a “fucking asshole,” California Court of Appeal Justice Gerald Brown referred to this phrase as the “Callahan epithet” to avoid having to repeat it continuously, “which arguably would assist its passage into parlor parlance.” And he reversed Callahan’s conviction:

A land as diverse as ours must expect and tolerate an infinite variety of expression. What is vulgar to one may be lyric to another. Some people spew four-letter words as their common speech such as to devalue its currency; their repetition dulls the senses; Billingsgate thus becomes commonplace. Not everyone can be a Daniel Webster, a William Jennings Bryan or a Joseph A. Ball. …

Fifty years ago the words ‘damn’ and ‘hell’ were as shocking to the sensibilities of some people as the Callahan epithet is to others today. The first word in Callahan’s epithet has many meanings. When speaking about coitus, not everyone can be an F.E. Smith (later Earl of Birkenhead) who, in his speech in 1920 in the House of Commons on the Matrimonial Causes Act, referred to ‘that bond by which nature in its ingenious telepathy has contrived to secure and render agreeable the perpetuation of the species.’