Meteors are more commonly seen between midnight and dawn than between dusk and midnight. Why?

Meteors are more commonly seen between midnight and dawn than between dusk and midnight. Why?

The King sent for his wise men all

To find a rhyme for W;

When they had thought a good long time

But could not think of a single rhyme,

“I’m sorry,” said he, “to trouble you.”

— James Reeves

(Thanks, Dave.)

“I would rather discover a single causal connection than win the throne of Persia.” — Democritus

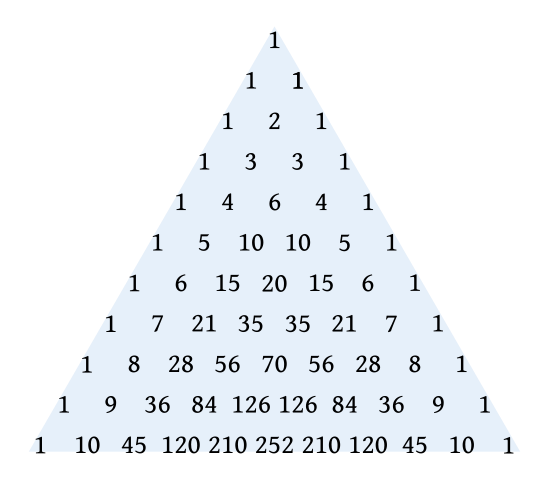

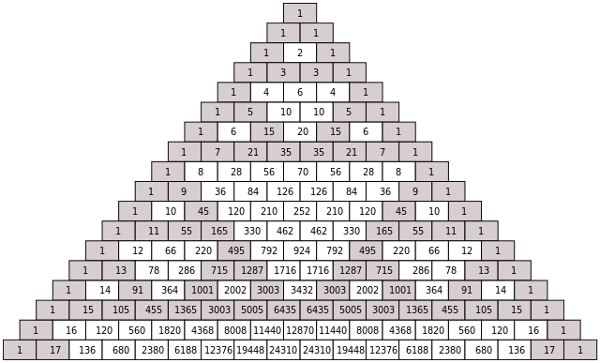

In 1653, Blaise Pascal composed a triangular array in which the number in each cell is the sum of the two directly above it:

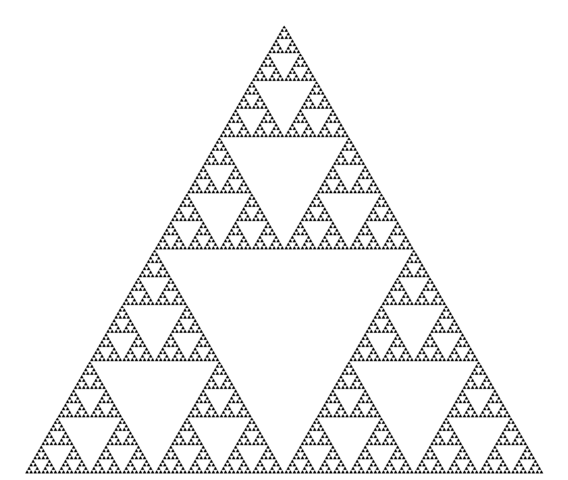

In 1915, Polish mathematician Waclaw Sierpinski described an equilateral triangle in which the central fourth is removed and the same procedure is applied to all the succeeding smaller triangles. Perplexingly, the resulting structure has zero area:

Interestingly, if the odd numbers in Pascal’s triangle are shaded, they produce an approximation to Sierpinski’s triangle:

And as this triangle grows toward infinity, it becomes Sierpinski’s triangle — an arrangement of numbers that takes the shape of a geometrical object.

‘Twas the nocturnal segment of the diurnal period preceding the annual Yuletide celebration, and throughout our place of residence, kinetic activity was not in evidence among possessors of this potential, including that species of domestic rodent knows as Mus musculus.

Hosiery was meticulously suspended from the forward edge of the wood-burning caloric apparatus, pursuant to our anticipatory pleasure regarding an imminent visitation from an eccentric philanthropist among whose folkloric appellations is the honorific title of St. Nicholas.

The prepubescent siblings, comfortably ensconced in their respective accommodations of repose, were experiencing subconscious visual hallucinations of variegated fruit confections moving rhythmically through their cerebrums.

My conjugal partner and I, attired in our nocturnal head coverings, were about to take slumbrous advantage of the hibernal darkness when upon the avenaceous exterior portion of the grounds there ascended such a cacophony of dissonance that I felt compelled to arise with alacrity from my place of repose for the purpose of ascertaining the precise source thereof.

Hastening to the casement, I forthwith opened the barriers sealing this fenestration, noting thereupon that the lunar brilliance without, reflected as it was on the surface of a recent crystalline precipitation, might be said to rival that of the solar meridian itself — thus permitting my incredulous optical sensory organs to behold a miniature airborne runnered conveyance drawn by eight diminutive specimens of the genus Rangifer, piloted by a minuscule aged chauffer so ebullient and nimble that it became instantly apparent to me that he was indeed our anticipated caller.

With his ungulate motive power travelling at what may possibly have been more vertiginous velocity than patriotic alar predators, he vociferated loudly, expelled breath musically through contracted labia, and addressed each of the octet by his or her respective cognomen — “Now Dasher, now Dancer …” et al. — guiding them to the uppermost exterior level of our abode, through which structure I could readily distinguish the concatenations of each of the 32 cloven pedal extremities.

As I retracted my cranium from its erstwhile location, and was performing a 180-degree pivot, our distinguished visitant achieved — with utmost celerity and via a downward leap — entry by way of the smoke passage.

He was clad entirely in animal pelts soiled by the ebony residue from the oxidations of carboniferous fuels which had accumulated on the walls thereof. His resemblance to a street vendor I attributed largely to the plethora of assorted playthings which he bore dorsally in a commodious cloth receptacle.

His orbs were scintillant with reflected luminosity, while his submaxillary dermal indentations gave every evidence of engaging amiability. The capillaries of his malar regions and nasal appurtenance were engorged with blood that suffused the subcutaneous layers, the former approximating the coloration of Albion’s floral emblem, the latter that of the Prunus avium, or sweet cherry.

His amusing sub- and supralabials resembled nothing so much as a common loop knot, and their ambient hirsute facial adornment appeared like small tabular and columnar crystals of frozen water. Clenched firmly between his incisors was a smoking piece whose gray fumes, forming a tenuous ellipse about his occiput, were suggestive of a decorative seasonal circlet of holly. His visage was wider than it was high, and when he waxed audibly mirthful, his corpulent abdominal region undulated in the manner of impectinated fruit syrup in a hemispherical container.

He was, in short, neither more nor less than an obese, jocund, superannuated gnome, the optical perception of whom rendered me visibly frolicsome despite every effort to refrain from so being.

By rapidly lowering and then raising one eyelid and rotating his head slightly to one side, he indicated that trepidation on my part was groundless. Without utterance and with dispatch, he commenced filling the aforementioned appended hosiery with various articles of merchandise extracted from a dorsally transported cloth receptacle. Upon completion of this task, he executed an abrupt about-face, placed a single manual digit in lateral juxtaposition to his olfactory organ, inclined his cranium forward in a gesture of leave-taking, and forthwith affected his egress by renegotiating (in reverse) the smoke passage.

He then propelled himself in a short vector onto his conveyance, directed a musical expulsion of air through his contracted oral sphincter to the antlered quadrupeds of burden, and proceeded to soar aloft in a movement hitherto observable chiefly among the seed-bearing portions of a common weed. But I overheard his parting exclamation, audible immediately prior to his vehiculation beyond the limits of visibility: “Ecstatic yuletide to the plenary constituency, and to that selfsame assemblage, my sincerest wishes for a salubriously beneficial and gratifyingly pleasurable period between sunset and dawn!”

(Author unknown)

clancular

adj. secret, private

“Special Correspondence. I learn from a very high authority, whose name I am not at liberty to mention, (speaking to me at a place which I am not allowed to indicate and in a language which I am forbidden to use) — that Austria-Hungary is about to take a diplomatic step of the highest importance. What this step is, I am forbidden to say. But the consequences of it — which unfortunately I am pledged not to disclose — will be such as to effect results which I am not free to enumerate.” — Stephen Leacock, The Hohenzollerns in America, 1919

“A tomahawk is what if you go to sleep and suddenly wake up without your hair, there is an Indian with.”

— University of Texas El Burro, 1969, from A Century of College Humor

You never laugh at anything nice. A comedy that ends with a laugh is a comedy that ends not with a solution but with a fresh disaster. At the end of Gogol’s The Government Inspector the real government inspector arrives; the trouble is just beginning. At the end of George F. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s Broadway comedy The Man Who Came to Dinner, the eccentric Sheridan Whiteside, who has wrought havoc in the lives of the Middle American family in whose home he is stranded by a broken ankle, walks out the door to universal relief, slips on the front step, and breaks his ankle again. According to Arthur Koestler, laughter does not truly release tension because it does not solve the problem; it fritters away energy in purposeless physical reflexes that make action impossible. Laughter is not a solution, it is a sign of the problem. As a number of writers have observed, there is a built-in contradiction between comedy’s two purposes, laughter and the happy ending. In its normal operation [the reaching of a happy ending] the function of comedy is to make the audience stop laughing.

— Alexander Leggatt, English Stage Comedy 1490-1990, 2002

An extraordinary scene took place on Saturday last at a small village within three miles of Middleton. A half-witted fellow named James Driscott had cruelly ill-used his donkey. He was told by several of the villagers that he would be brought up before the magistrates and severely punished; but his informants said that if he consented to do penance for his inhuman conduct, no information should be laid against him. Discott gladly agreed to the proposed terms. The donkey was placed in the cart, and its owner, with the collar round his neck, was constrained to drag his four-footed servant through the village. The scene is described by a local reporter as being the most laughter-moving one he had ever witnessed.

— Illustrated Police News, Jan. 22, 1876