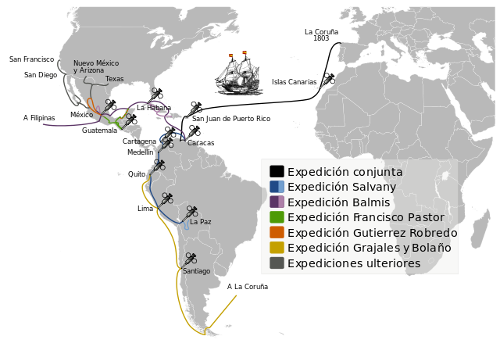

Smallpox ravaged the New World for centuries after the Spanish conquest. In 1797 Edward Jenner showed that exposure to the cowpox virus could protect one against the disease, but the problem remained how to transport cowpox across the sea. In 1802 Charles IV of Spain announced a bold plan — 22 orphaned children would be sent by ship; after the first child was inoculated, his skin would exude fluid that could be passed to the next child. By passing the live virus from arm to arm, the children formed a transmission chain that could transport the vaccine in an era before refrigeration and other modern technology was available.

It worked. Over the next 10 years Spain spread the vaccine throughout the New World and to the Philippines, Macao, and China. Oklahoma State University historian Michael M. Smith writes, “These twenty-two innocents formed the most vital element of the most ambitious medical enterprise any government had ever undertaken.” Jenner himself wrote, “I don’t imagine the annals of history furnish an example of philanthropy so noble, so extensive as this.”