A problem from the 2004 Moscow Mathematical Olympiad:

An arithmetic progression consists of integers. The sum of its first n terms is a power of two. Prove that n is also a power of two.

A problem from the 2004 Moscow Mathematical Olympiad:

An arithmetic progression consists of integers. The sum of its first n terms is a power of two. Prove that n is also a power of two.

Given his necessary perfections, if there is a best world for God to create then it appears he would have no choice other than to create it. For, as Leibniz tells us, ‘to do less good than one could is to be lacking in wisdom or in goodness.’ Since it is strictly impossible for God to be lacking in wisdom or goodness, his inability to do otherwise than create the best possible world is no limitation on his power. But if God could not do otherwise than create the best world, he created the world out of necessity, and not freely. And, if that is so, it may be argued that we have no reason to be thankful to God for creating us, since, being parts of the best possible world, God was simply unable to do anything other than create us. … [Leibniz’s reasoning] cannot avoid the conclusion that God is not sufficiently free in creating, and is therefore not a fit subject of gratitude or moral praise for creating the best.

— William L. Rowe, Can God be Free?, 2006

This is startling — in 1500 artist Jacopo de Barbari produced an aerial view of Venice, assembled from six woodcuts on large sheets of paper. The full image fills nearly 4 square meters; it was probably assembled from sightings taken by surveyors in bell towers around the city.

The artist’s meticulous attention to detail is reflected in the flat roof on the bell tower in St. Mark’s Square, which was added after a fire in 1489. When the tower was restored in 1514, the woodblocks were updated to reflect the change.

My wife and I walk up an ascending escalator. I climb 20 steps and reach the top in 60 seconds. My wife climbs 16 steps and reaches the top in 72 seconds. If the escalator broke tomorrow, how many steps would we have to climb?

After seeing a manuscript of On the Origin of Species in April 1859, the Rev. Whitwell Elwin suggested that Darwin write about pigeons instead.

“This appears to me an admirable suggestion,” he wrote. “Everybody is interested in pigeons.”

An odd feature from the Baltimore Sun of Oct. 5, 1902: Alfred Hermann of Bakersfield, Calif., pledged to circle the world in a year and a half wearing a pair of steel handcuffs, and to earn a livelihood while doing so. If he succeeded, his friend Al Armstrong agreed to finance a medical education for him.

At the time of the interview, Hermann had reached the East Coast six months after setting out from California on March 22, having visited Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Salt Lake City, Denver, Kansas City, St. Louis, Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York. “From here I ship to London, and from there go to Paris. After leaving Paris I intend to visit Berlin. At St. Petersburg I will connect with the Trans-Siberian railway and reach the west coast of China,” whence he planned to continue to Japan and embark for San Francisco. His only means of earning money along the way was to sell pictures of himself and give “exhibitions of the different exercises that it is possible for a man to take with his hands steel-braceletted.”

Under the terms of the agreement, Hermann could remove the manacles at night, “for health’s sake.” “At each stopping place the cuffs are unlocked, when he retires, by some responsible person, preferably the landlord of the hotel where he stays. Upon departing the landlord locks the cuffs, seals a bit of paper over the key opening, writes his name thereon and also writes his name in a book that Hermann carries, with the name of place, date, etc., affixed in regular postmark form. The key is then placed in Hermann’s pocket.”

I don’t know whether he made it. “The boy’s got grit in him,” Armstrong said. “I like his pluck; but, of course, he doesn’t stand much chance of winning. His enthusiasm will be likely to give out when he’s up against it in China or Russia or some other outlandish place where nobody understands the American lingo and will lock him up for a lunatic or a jailbird. However, I’ll make good if he will.”

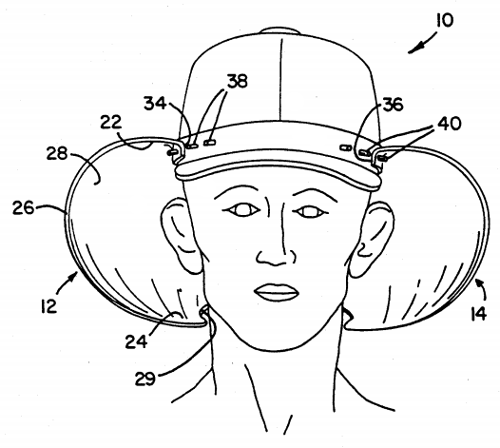

Pauline Klaws patented this “appliance for assisting the hearing” in 1902. “It is designed to be worn at lectures, concerts, theaters, and meetings by persons having defective hearing and by the people generally who at such entertainments or meetings, particularly large meetings, are unable or have difficulty in hearing a speaker.”

By 1993 this had evolved into the version below, patented by Mark Tilkens, who found it “particularly useful in hunting of game such as deer, to enhance a person’s ability to hear noises which otherwise may be drowned out by background noise.”

Literature often inspires music, but the reverse is less common. Here’s an intriguing exception: In Music and Literature: A Comparison of the Arts (1948), Calvin S. Brown argues that the third part of Thomas De Quincey’s 1849 essay “The English Mail-Coach” is deliberately structured as the literary equivalent of a musical fugue.

That part of the essay, titled “The Dream-Fugue,” tells how De Quincey’s dreams were dominated by a recent experience in which his carriage had nearly collided with that of a young woman. As De Quincey describes his dreams, the fugue subject is a group of ideas (speed, urgency, and a girl in danger of sudden death) that remain static while the shifting settings and details act as a contrapuntal accompaniment: In the first section a girl dances on a ship that is run down by another ship; in the second she escapes; in the third she runs along a shore and is engulfed in quicksand.

[The] middle part begins with Section IV, and is constructed exactly as it should be. The news of Waterloo and victory, the coach carrying that news, the cathedral seen in the distance and rapidly approached and entered — all these are presentations of material closely connected with the subject; but there is a definite departure from the set statements of this subject found in the exposition. In the middle section we expect at least one direct restatement of the subject in addition to this episodic material; hence we look for another vision of sudden death. We are not disappointed. After a considerable interval the girl of the visions, now an infant, appears directly in the path of the coach, which is thundering up the aisle of the vast cathedral. There is a moment of suspense, and then, just as death seems certain, she vanishes. After a dramatic pause, she reappears as a full-grown woman, on an altar of alabaster, within the cathedral and yet among the clouds. On one side of her is dimly seen the shadow of the angel of death, and on the other her better angel prays for her. What we have here is simply a recurrence of the subject and answer, the counter-subject appearing with the answer only. It will be observed that the answer always saves the victim from the immediate peril presented in the subject, but keeps the idea of further danger. In the single instance where fugue-form does not demand an answer (Section III), the girl goes on to her fate.

In the book, Brown even presents a chart identifying the exposition, the development, and the final section of the fugue. “Most commentators have brushed aside the title of this section with some meaningless comment, but De Quincey’s knowledge of music and his interest in it, together with his passion for intellectual analysis, make it reasonable to suppose that his title was something more than a fanciful name. Actually, De Quincey’s method of producing the musical effect was to follow, as far as the limitations imposed by a different medium would permit, the structure of the musical form. He succeeded in following it far more closely than has been generally realized.”

linguished

adj. skilled in language

logofascinated

adj. fascinated by words

logodaedaly

n. cunning in words; “verbal legerdemain”

oligoglottism

n. limited knowledge of languages

In North Wales the Welsh word for ‘now’ is ‘rwan.’ In South Wales it is ‘rwan’ spelt backwards, viz., ‘nawr.’ It is conjectured that the first North Walian who made use of the word was standing on his head at the time, and that his pronunciation became general.

— The Cambrian, May 1901