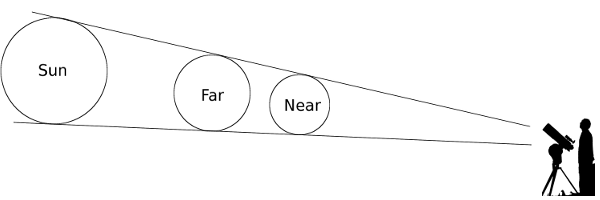

In 1962 a Swedish motorist was fined for leaving his car too long in a space with a posted time limit. The motorist objected, saying that he had removed the car in time and then happened to return to the same spot later, resetting the time limit. The policeman defended his charge, saying that he had noted the positions of the valves on two of the tires — the front-wheel valve was in the 1 o’clock position, the rear-wheel valve at 8 o’clock. If the car had been moved, he argued, the valves were unlikely to take the same positions.

The court accepted the motorist’s claim, calculating that the chance that the valves would return to the same positions by chance was 1/12 × 1/12 = 1/144, great enough to establish reasonable doubt. The court added that if all four valves had been found to be in the same position, the lower likelihood (1/12 × 1/12 × 1/12 × 1/12 = 1/20,736, it figured) would have been enough to uphold the fine.

Is this right? In evaluating this reasoning, University of Chicago law professor Hans Zeisel notes that this method is biased in favor of the defendant, since the positions of the valves are not perfectly independent. He later added, “The use of the 1/144 figure for the probability of the constable’s observations on the assumption that the defendant had driven away also can be questioned. Not only may the rotations of the tires on different axles be correlated, but the figure overlooks the observation that the car was in the same parking spot. When a person leaves a parking place, it is far from certain that the spot will be available later and that the person will choose it again. For this reason, it has been said that the probability of a coincidence is even smaller than a probability involving only the valves.”

(Hans Zeisel, “Dr. Spock and the Case of the Vanishing Women Jurors,” University of Chicago Law Review, 37:1 [Autumn 1969], 1-18)