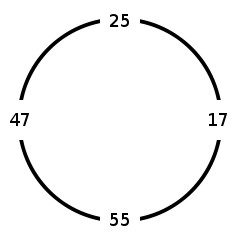

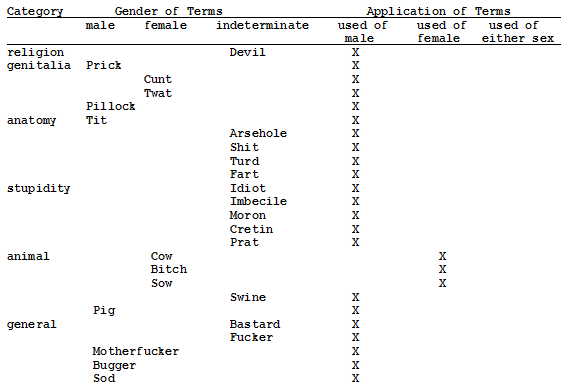

In An Encyclopedia of Swearing (2006), University of the Witwatersrand linguist Geoffrey Hughes notes that terms of vehement personal abuse seem to attach disproportionately to the male sex:

In his analysis, even terms derived from female anatomy are applied to men rather than women (at least in British usage). Terms such as bugger, motherfucker, and sod[omite] understandably derive from sexual role, but why are devil, fucker, moron, and cretin applied generally to men and not women?

“All the indeterminate terms, such as bastard, idiot, and shit, which should logically be ‘bisexual’ in application, are invariably applied only to males,” Hughes writes. (Also, strangely, there seems to be no vehement term of abuse that’s used freely of both sexes.) “However, the historical perspective shows one significant trend, namely that several of the terms, like bitch and sow, were first used of males (or of both sexes) and only later applied exclusively to women.”